It was May 8, 2000 when, for the first time, I felt the cold steel of police handcuffs close around my little wrists. I was 8–

According to Prison Policy Initiative, 68% of people in state prisons were 18 or younger at the time of their first arrest: I ended up in prison at the age of 17.

Whether his intention was to scare me or punish me in some way, the simple fact is that actions such as his often cause trauma for children in addition to the issues that come with growing up in an impoverished environment.

According to Richard Mendel of The Sentencing Project, youth who become involved in the justice system are seven times more likely than other youth to suffer traumatic experiences. This research finds that trauma can impede children’s healthy brain development, harm their ability to exercise their cognitive and volitional functions and heightens risks of delinquent behavior.

Although police violence is beginning to be a huge topic in America, the type of violence perpetrated against inner-city youth due to roll backs of needed government welfare policies and racial targeting, in particular, often goes under reported. To minimize or ignore such physical and psychological violence and the effects they have on the development of the youth, is to ignore the state of communities suffering from what seems to be an unbroken cycle of random acts of violence, drug abuse and poverty.

One inmate, a 46-year-old Black man who has been incarcerated for 24 years, told me he was homeless by the age of 13 and that when police caught him sleeping in an abandoned building, instead of being shown care and compassion, he was beaten and taken to jail for trespassing.

Once released, he was still alone and had no source of help or support to turn to – especially the people sworn to serve and protect – and so he continued living in abandoned buildings and crack houses, until, by the age of 16, he had smoked crack and had developed substance abuse issues. By the age of 22, he was serving 32 years for an armed robbery murder that he maintains he is falsely convicted of.

In a time when punitive crime measures have drastically increased alongside tough on crime rhetoric, it has been Black, Latino and Native Indian youth who have been disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration and social stigmas. According to studies conducted by sociologist Victor M. Rios, 95% of all juveniles sent to adult court are minorities.

John J. Dilulio, director of Faith Based and Community Initiatives for President George W. Bush, and William Bennett, former Ees

Dilulio stated, “There is very little that we can do to alter life experiences that make some boys criminally “at risk”… let the government Leviathan lock them up, and when prudence dictates, throw away the key.”

With rhetoric that labels youth as hopeless and risks to society, what are the youth themselves supposed to believe they can achieve or expect? With little to no programmatic or financial resources to provide youth support for positive development, and politicians calling for punitive policies that treat juveniles as adults for their mistakes, more Black, Latino and Native Indian youth are being corralled into the criminal justice system without receiving the help necessary to develop hopes and dreams that reach further than the labels placed upon them.

Politicians, police and other advocates of being tough on crime say that kids like myself and many similarly situated youth made our choices and harsh sentences are necessary for the benefit of society.

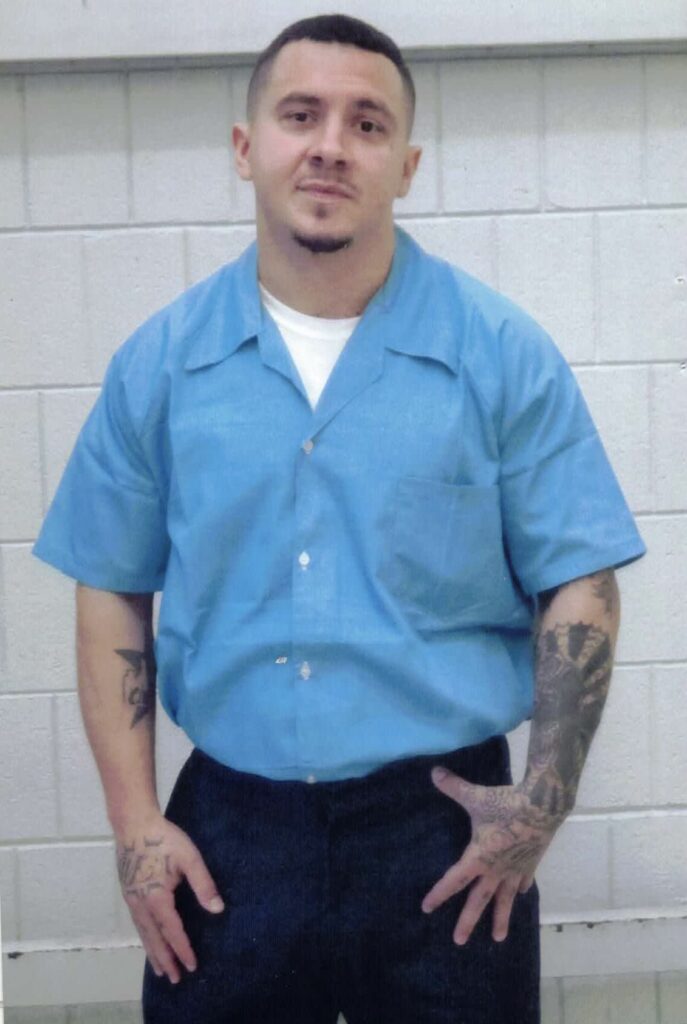

However, when statistics and studies show that Black, Latino and Native Indian youth are disproportionately targeted as criminals, 8.3 times more likely to be tried as adults than white youth and that the majority of arrests are made in struggling and destitute communities, it should lead you to question whose society is benefitting from the mass incarceration of young, and often poor, minorities.Today, after almost 15 years of incarceration, when I look around it’s not just the familiar set of state blue clothing I see on each individual in here that stands out, it’s the overwhelming number of Black and Brown faces that seem common to the uniform; what is just as common are our stories of being minorities in poor neighborhoods and our shared experiences of growing up in prison in the age of mass incarceration

No Comments