“Oh, no! What next?” Betty moans, as her fellow widow and sister Suzanne snatches the binoculars from her hand.

“What’s the old rascal up to now?” Suzanne asks, scanning their neighbor’s yard through the kitchen window. “I can’t see him. Where’d he go?”

“He went back inside, probably to hide his face in shame after hanging up those raggedy-ass tee shirts and disgusting jockey shorts.”

Suzanne focuses the binoculars, emits a strangled “Yeoww!” “My God, judging by the holes in their crotches, you’d swear that he was firing BBs from his bunghole instead of farts.”

“It’s disgraceful, that’s all. You’d think that the old fizzle was poor or crazy, and I know for a fact he’s neither, just cheap,” Betty decides.

“Well, there’s a cure for that,” Suzanne reckons, “and that’s a woman. How long has it been since his wife died? Seven years? Eight?”

Betty lights a cigarette, coughs. For the last two years, her unreciprocated affection for her slovenly neighbor has been slowly growing. “I believe it will be eight years, come January. Too damn long for any man to live alone.”

Suzanne lays down the binoculars, pours herself a cup of coffee. “Just imagine what his house smells like,” she speculates, “between that stupid cat and his old man’s BO – and I hate to even think about his toilet! – I’ll bet a good whiff would choke a buzzard.”

Her sister draws the window curtain, sits down. “I’ll bet you double or nothing, Sis, that he hasn’t bought any clothes since his wife passed, either.”

Suzanne looks at Betty; Betty looks at her. They both glance at the wall calendar: Three weeks until Christmas. And by the fusion of their shared thoughts, they forge a benevolent golem which they will order to Walmart to buy a twelve-pack of Hanes jockey shorts.

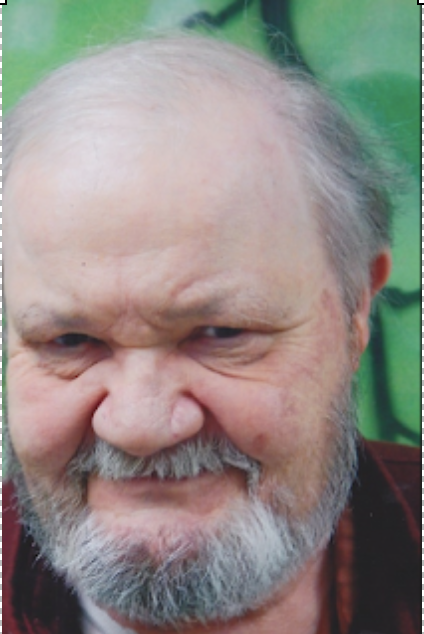

Sean McNeal, the shameful old man of the sisters’ obsessions, is a self-sufficient widower of sixty-three, living quite modestly on his savings and a monthly disability check for his bad knees. Lacking binoculars or a telescope, he has occasionally spied on his only visible neighbors – the Sizemore sisters – through a 4×16 power hunting scope that he has never bothered to mount upon his open-sighted 30-06 deer rifle. From his back door stoop, off which he frequently urinates, it is only a good Tiger Woods seven-iron shot to the sisters’ kitchen window. Although he is beloved by three grown daughters and three granddaughters, and had “known” in the Biblical sense close to a hundred women before he was married, Sean fancies himself a bit of a misogynist, and occasionally delivers impromptu, alcohol-fueled harangues about the deviousness of the female sex to his supremely detached housecat, who considers him a surrogate father to her frequent litters. Meanness isn’t in him, and children and animals alike can sense it. Time’s ceaseless dripping has washed away his former blemishes, and by a slow stalagmite accretion reinforced his virtues.

Aware of the anomaly between his pretended distrust of all things womanly, and his grudging acceptance of their works, he sometimes muses ironically that, if he’s not careful, he could inadvertently attract one of the very creatures that he’s anxious to repel. But then he wards against that possibility with a hearty swig of cheap vodka, strokes his no-name cat for good luck, and chuckles.

Betty and Suzanne, however, think it highly unlikely that Sean will attract anyone, except possibly the police. On far too many nights, they have heard him cursing out the raccoons that raid his cat’s front porch food dish, threatening in the most obscene terms to turn them into Davy Crockett hats.

“My, my, such language!” Betty complains. “And to think that he’s so nice to his cat and his grandchildren, never even raises his voice.”

“Yes, it’s a most regrettable failing,” Suzanne concurs. “I’ve often watched him playing with his grandkids, laughing and smiling, and then no sooner than they’re gone, and he gets a few drinks in him, it’s ‘F’ this, and ‘F’ that, and ‘GD’ the blankety-blank ‘coons or the ‘MF’ing’ yuppies.”

“Well, it’s perfectly obvious that he’s been living alone far too long,” Betty concludes. “He’s a textbook example of how some men can deteriorate when left to their own devices.”

“Especially when they drink as much as he does,” Suzanne adds.

They light cigarettes, exchange looks, debate when to let loose the golem, who is itching for action.

Sean is rocking contentedly on his front porch swing, working on his third beer of the day, when he sees Betty coming down the road. With a smile, she crosses his lawn and plunks a basket on his picnic table.

“I sure hope there isn’t a litter of kittens in there,” he jokes. “I just got rid of the last batch, and judging by her belly, Miss Hot Pants over there (indicating with his chin a slate-gray tigress dozing in the sun) is fixing to drop another.”

“Don’t be silly,” she admonishes, removing a Tupperware bowl from the basket. “I just thought that you might like to try some of my shepherd’s pie. I made a little extra just for you.”

Uh-oh. He senses a trap. If he spurns her offer, he’ll hurt her feelings. If he accepts it, tells her that it was yum-yum-good, then what? Next thing I know, she’ll be down here all the time, nosing into my affairs and monkey-wrenching my life. I know better than to feed a stray cat, but what the hell do you do when the damn cat wants to feed you?

While he’s pondering these equally unsatisfactory outcomes, his anonymous cat catches a whiff of the food and leaps on the table, its uplifted tail a furry exclamation mark.

“Well, that’s mighty thoughtful, Betty,” he allows, sweeping the creature to the ground. “I guess I better take it inside before Miss Greedy or the god… uh… darned ‘coons get into it. Hang tight, I’ll be back in a jiffy.”

Dying, absolutely dying, to get inside his house to assess the damage wrought by eight years of second-bachelorhood, she offers to put it away herself. “No, you just sit back and relax. I’ll run it in myself. I’ll even bring you back another beer,” she insists. “No problemo.”

No problem?! Not only does she show up uninvited with a Trojan horse, she wants to push it inside my castle herself! Gotta think of something quick!

“Nah, that isn’t such a good idea, right now,” he says, desperately. “I just set off a few flea bombs downstairs. Seems like Miss Hussy brought home some of her boyfriend’s cooties, as well as his brats.”

Betty frowns, looks at his open front door, smells a rat.

Sean notes her suspicion, gauges the strength of her bullshit detector, manages to avoid a showdown. “Tell you what, neighbor, suppose I just hold my breath and scoot it in real quick-like?” Before she can object, he snatches up the bowl, takes a deep breath, and plunges through the door. When he returns a half-minute later, holding his nose, Betty is on the swing, smoking with quick, angry drags, her scheme temporarily derailed. But ever-resourceful, she resumes the attack on another front.

“When the smoke clears, Sean,” she wheedles, “Suzanne and I can do your floors with our carpet cleaning machine, while you flea-dip your cat in the yard. We owe you a favor, anyhow, after your son plowed our driveway after the big storm last winter.”

If I know my son, he was hoping to plow his way into your bed, he guesses.

“Betty, I sure appreciate your kind offer, but my daughter Katie already rented one,” he lies.

So much for Plan B, she thinks. Back to the old drawing board. “Well, in that case, I might as well go. I’ll stop back tomorrow, when the air has cleared. Maybe you can give me a house tour – I just love the architecture in these old homes.”

Right. And then you can open the horse’s belly hatch when I ain’t looking, and have me, but good.

“Suppose I bring it to you? A little exercise will do me good.”

Foiled again! she fumes. The old goat must be hiding something. Maybe he’s one of those hoarders – trash to the ceiling, cat shit six inches deep, and – Dear God! – what does his bathroom look like? With a shudder, she visualizes a public toilet in Tijuana, the Augean stables before Hercules showed up, an overflowing Porta Potti at Woodstock. Suddenly, in a flash of inspiration, a “can’t fail” plan to penetrate Sean’s fortress pops up. “That’ll work. One of us ought to be home, for certain. See you tomorrow,” she says, walking away.

“So, he wouldn’t let you in,” Suzanne remarks. “Now, what? It would be much easier to rescue the old coot if we knew what we’re saving him from.” She lights a cigarette, contemplates its smoke as if a problem-solving genie were lurking within it. “Maybe he doesn’t need any help. Maybe his house is neater than ours. God knows, he has enough time on his hands.”

Betty rips the cigarette from her sister’s mouth, sniffs the lit end. “What? Are you smoking angel dust? It’s impossible for anyone’s house to be cleaner than ours! Even our own daughters think we’re a pair of anal-obsessives!”

“As opposed to penile-obsessives, like them?” Suzanne jokes.

Irritated by the crude witticism, Betty takes a cowboy-sized lungful of nicotine from her sister’s Marlboro, wonders aloud what they ought to try next.

After a bit, Better announces, “Look, I have it all figured out. He’ll be returning our bowl sometime tomorrow, and as soon as he leaves his house, you run out the back door, cut through the woods, and sneak in his back door.”

“Hmm,” Suzanne hmms. “That might work.”

“Sure it will, as long as he doesn’t lock up first, which I doubt. You get on in there, girl, and bring back the ‘true gen’, like Hemingway called it.”

Suzanne butts her cigarette, eyes her sister through her last exhalation. “You got a thing for men like that, don’t you? Tough old cusses who drink too much and love cats. Sort of heats you up, huh?”

Betty fires up a Newport, blows a plume of smoke in Suzanne’s face. “So, what if I do? I think it’s high time to re-domesticate that old goat before he goes feral.”

Suzanne thinks that it’s too late, but says nothing. Actually, she wouldn’t half-mind trying to tame the old bronc herself, but doesn’t want to initiate a civil war. No, let her have him, thinks she, as long as I can join the hunt.

The sisters are a year apart; Betty the oldest at forty-seven. They each have a son and a daughter bedeviled with the puzzling “No-Time Syndrome”, a contemporary ailment whose insidious ravages rob its victims of the necessary time to visit their lonely mothers, who, conversely enough, always seem to have an excess of expendable time, a paradox which a skeptic might cite to account for the Sizemore sisters’ all-consuming machinations to ensnare and tame a harmless old man.

It so happens that Betty deplores her widowhood in the manner that nature abhors a vacuum, a fact that bodes ill for Sean, who quite innocently is being drawn towards the event horizon of her need.

Her infatuation has ripened slowly, nurtured by her observations of Sean’s interactions with his grandchildren and their various pets, all infallible judges of human character. Yes, the old reprobate drinks, but never drives; sings to the moon on occasion, but never off-key. True, he hadn’t gone out of his set ways to welcome them to the neighborhood with a plate of home-baked goodies or merely a hearty howdy-do, but he always has time to chat with them when they pass his close-to-the-road home during their morning walks. And neither sister doubts for a moment that it is he who asks his son to plow their driveway every time it snows. For more than a year, Betty has been offering him covered dishes, hoping to be asked into his home, but so far he has put her off with one excuse after another, even though he has come to anticipate her visits.

Over time, Betty has concluded that Sean has been placed in her path by Fate, a notion reinforced every time she sees another of his shirt buttons replaced by a safety pin, or shudders at a duct-taped rip in his britches, or obsesses upon the probable/horrible/deplorable state of his abode, whose tidiness cannot have been enhanced by his sole source of heat, a wood-burning stove.

Moreover, the mere existence of a likely hoorah’s nest so close to her and Suzanne’s spotless home disturbs Betty to no end. She sometimes fantasizes that the unchecked slovenliness festering in Sean’s home might osmose across his crab grass/dandelion/plantain-infested lawn, slither through the property line fencerow, ooze across the sisters’ horseless horse pasture, and BURST THROUGH THEIR FRONT DOOR TO ESTABLISH A BEACHHEAD OF FLEA-RIDDEN FILTH!

Thus, in Betty’s opinion, the best way to forestall such an intolerable event is to break the head stallion to the bit and saddle, clean up his stable, and ride him into the happy sunset years of their lives. Or something like that, she fuzzily dreams.

The next day, just after noon and before his first drink, Sean decides to return the bowl. Can’t have the girls thinking I’m a drunk, he optimistically thinks. Next thing I know, they’ll be no-funning me to death.

Out the front door he goes, leaving it and the back door unlocked. Hell, I’ll only be gone a few minutes, then I can siphon a jug of hard cider from the basement barrel and listen to some “classical” music: a little Hank and Lefty, and maybe some Patsy Cline, if I wind up shit-faced and sentimental.

Meanwhile, the gals have been up since dawn, waiting for him to leave home.

“Here he comes!” Betty cries, lowering the binoculars. Without a word, Suzanne rushes out the back door, scoots behind the barn, and ducks into the woods. A few minutes later, as Sean is knocking on the sisters’ front door, Suzanne sneaks through his unlocked back door, chortling with glee.

“Morning, Betty,” Sean says, when she opens the door.

“Morning to you, Sean,” she replies. “How about a nice warm cup of coffee on a cold day? I bet you haven’t set foot in here since we remodeled it, have you?”

“Nope, not since 1985, I believe it was, the year my drin… uh… hunting buddy Peck died.”

“Well, suppose I give you a quick tour, then? I’m kind of proud of our makeover.”

O Lord! he inwardly moans. Not the dreaded “house tour”! I should have stuck that damn bowl in her mailbox and beat feet!

Betty takes his silence for an assent, and launches into a time-killing spiel, points out her custom granite countertops and the imported Castilian tile floor, describes with the sort of florid encomiums usually bestowed upon an only child the exotic features of the industrial-grade gas range and the set of copper-bottomed French cookware, plus the boxed set of $100 apiece Japanese knives.

Meanwhile, in Sean’s kitchen, Suzanne notes with distaste the grease-blackened fifty-year-old stove, stares in disbelief at the glassless cabinet in which not two of the cracked and chipped plates are of a match, nor the yard sale drinking glasses and recycled peanut butter jars. With trepidation, she gingerly opens the refrigerator to find it stocked with two cases of beer, a jug of ice water, a gallon jar of home-pickled peppers, packages of lunch meat and sliced cheese, an assortment of condiments, and little else. Turning away in disgust, she is confronted by a disassembled lawn mower engine on a kitchen table flanked by two thirty-gallon trash barrels half-full of discarded tin cans and flammable rubbish destined for the backyard burn pit. With a hand over her gaping mouth, Suzanne warily enters Sean’s dining room.

Betty ushers Sean into her dining room, beaming with pride. “We found this magnificent walnut trestle table in a back-road Lancaster County antique store,” she confides. “Only $600, including these darling chairs! Aren’t they wonderful?”

He nods politely, thinking that she’s a damn fool. Pretty tables don’t make for pretty eating. Christ, hasn’t she ever heard of secondhand stores?

Suzanne stands in the old man’s “dining room”, which is dominated by a large wood-burning stove on a flagstone platform and a floor-to-ceiling stack of firewood along one wall. A fifty-gallon steel barrel filled with kindling wood sits next to an unused radiator stacked high with old newspapers; the fake wooden beams above it are festooned with filthy cobwebs; the bare wood floor dark with grime. A wobbly table, which might bring $10 at a yard sale, is covered with a scrim of empty beer cans and hunting magazines. Two mounted deer heads, their antlers used for hat racks, glare at one another from opposite walls. Muttering to herself, Suzanne enters the living room.

“Isn’t this a lovely Kashmir rug?” Betty enthuses. “I shiver when I consider its cost, but then, beauty is its own reward.” She drains her coffee cup, lights a cigarette, smiles brightly.

Sean glances at the rug; pretends interest. “Mighty nice, but then, mine ain’t no slouch, either.”

Startled by his assertion, she asks, “So… you have an Oriental rug, too? Where did you buy it? Philly? New York?”

He finishes his coffee, yearns for a chew of tobacco, but doubts if she’d appreciate him using her good china for a spit cup. “Actually, I didn’t really buy it, I sort of found it along the curb in Wyomissing – you know, that million-dollar West Reading suburb where Taylor Swift was raised on a Christmas tree farm.”

“There aren’t any farms in Wyomissing,” Betty objects.

“Right, just like there isn’t any country in her music. But that ain’t my point, which is that I got my rug for free, and except for a pretty nasty burn that you can’t see anyway once you set a chair over it, it’s every bit as handsome as yours,” he observes, much to Betty’s annoyance.

Suzanne stands upon Sean’s salvaged rug, guessing it was machine-woven in Georgia, USA, not Georgia, Caucasia. Besides its need of a good cleaning, telltale lumps around its perimeter hint of swept-under dust elephants. Two sagging easy chairs older than Betty face a boxy ‘80s-era TV atop a wooden crate. Resting on a counter beneath a wall of well-filled bookshelves is a coiled-to-fit copperhead snake inside a jar of rubbing alcohol. Squatting next to it, the mummified husk of a leopard frog mocks its former nemesis. Piles of winter clothing half-conceal a stringless guitar upon a wood Army surplus bivouac table; a pair of hip boots lay beneath it. From one corner of the room, yet another stuffed deer head contemplates an incongruous Renoir print hanging next to a tanned rattlesnake skin and a framed disorderly conduct citation (fine and costs, $106) from 1981. Sorry, oh so sorry, that she neglected to bring a camera, Suzanne proceeds circle-wise to the last downstairs room, the utility room between the front door and the kitchen.

“Say,” Sean asks Betty, “where’d your sister get to? Out doing her Christmas shopping?”

“No, she’s out in the woods, looking for crow’s feet and ground ivy to make door wreaths,” she lies.

“Well, tell her I’m sorry that I missed her when she comes back – I gotta go before Miss Pussy Cat gets jealous and kicks me out of bed.”

Uh-oh! Thinking quickly, Betty asks Sean to check her upstairs toilet. “Sometimes the water just runs and runs,” she complains, although in truth, it has never dared to do any such thing.

“All right, dearie, I’ll do it just for you,” he sighs, loath to subject his achy knees to needless strain, the same excuse he uses to rationalize his partiality for pissing from either his front or back porch, depending upon the time of day or night, and the likelihood of traffic. As he laboriously mounts the stairs, he lamely jokes, “I get the runs now and then, too, but they’re usually from too much beer, which I imagine ain’t the case here.” Betty glances at her wristwatch, offers a lame grin of her own.

Suzanne finds the final room crammed wall-to-wall with a dusty upright piano, a large electric generator and an air compressor, a variety of power tools, a washer and dryer – the latter filled with empty beer cans – and a litter box so befouled that its only patron has chosen to shit on the floor rather than soil its paws. Properly aghast, aware of the fleeting minutes, she rushes upstairs to the bathroom, believing as all women do that the condition of a bachelor’s bathroom reveals the degree of his domestication, or lack thereof.

Sean flushes the toilet once, twice, three times; removes its lid; peers inside; jiggles the float. The water refills the tank, then stops each time. “Looks fine to me,” he says. “There was probably a hunk of dirt caught in the gasket. Must’ve washed free.” He replaces the lid, checks his watch, informs Betty that, “I usually charge fifty bucks a visit, plus parts and labor, but seeing that it’s almost Christmas, I’ll settle for thirty.” He almost adds, “Cash or trade,” but realizes at the last second that she might take his joke for an invitation that he has no intention of honoring. Or would I? he worries.

But Betty needs no invitation, and croons, with fluttering eyelashes, “Oh, Santa, baby, I’m sorta starved for cash, right now. Do you think I could maybe work it off somehow?”

Taken aback, Santa fidgets uneasily, forces out a ho-ho, and descends the stairs, temporarily speechless.

Suzanne stumbles downstairs, speechless herself, fleeing a sight that might have paralyzed Perseus, shield or not. Had she been a cat, and Sean’s indescribably horrid toilet a litterbox, she would’ve shit on the floor, too, which judging by the suspicious brown spatters upon the deteriorated linoleum, someone may have already done. The duct-taped seat was bad enough; the lidless tank propped up by several two-by-fours worse; but terrible beyond reckoning was its bowl, the cleansing of which would’ve defeated Hercules, even had he possessed a sand blaster and a diverted river.

Had she taken a minute to visit Sean’s bedroom, the cleanest room in the house, she might have noticed his cat asleep on the bed. Awakened by Suzanne’s horrified screech, it leaps to the floor to follow her downstairs and out the back door, where it watches Suzanne flee into the woods, mission accomplished.

When Sean returns, the cat is eating from its porch dish. Hmm, he muses, she was in the house when I left. Although he once owned a dog that could turn doorknobs with its paws, he doubts like hell that Miss Floozie has mastered the same trick. He recalls Betty’s fishy excuse for her sister’s absence, reflects upon the drawn-out house tour and the unbusted “busted” hopper, and suspects that he was being stalled. Yep, the gals are up to something, he concludes, but what?

“So, Sis, just how bad was it, then?” Betty wonders.

“Bad? Bad would be a sinkful of dirty dishes, not an exploded engine on the kitchen table and a sinkful of dishes covered with mold!” She takes a sip of coffee, shudders at the memory. “Bad would be your typical bachelor mess – nothing that a few days of old-fashioned elbow grease couldn’t fix. But, honey, we ain’t talking your run-of-the-mill bad here, we’re talking double-barreled, V8-powered, triple-X-rated appalling! It resembles the aftermath of a two-week wino convention. Oh, Lord, Betty, I’m surprised his cat hasn’t left!”

Betty listens without comment; her suspicions confirmed. Is it too late to save him? she frets. She weighs his drawbacks against his positive traits, puts a mental digit upon the latter’s side of the scale, and replies in the affirmative to her unvoiced query. She is constantly reminded by the ticking of her internal clock that she is growing old, and realizes that as much as she enjoys her life with Suzanne, she wants and needs a man’s love more, even that of a sixteen-year-older rogue bull like Sean. And, she thinks, hopes, senses with her woman’s intuition, I think he might have some to spare.

December passes apace; buck season comes and goes; a light snow does the same. Sean gives the sisters some venison steaks and a margarine tub of deer burger. Betty returns the favor four times over with home-baked pies and cakes, and before their tummies realize it, Christmas is but a few days away. Sean intends to exchange presents with his daughters and grandchildren on Christmas Eve; he and Miss No-Name will exchange theirs on Christmas morn. Or so he jokes.

However, Betty has another idea. A better idea. A bold idea, even. Only a generation ago, a lady would never have even considered such a plan, let alone gone through with it, but back then, too, most widows died lonely and alone. And Betty has desire Number Zero to emulate those terminally repressed gentlewomen. No, she will beard the old rascal in his lair to better persuade him of his erroneous ways.

Finally, it is Christmas Day. The sisters’ daughters and grandchildren have come and gone, off to visit the other grandmothers, none of whom are in love with a semi-barbarian.

“When are you taking Sean his present?” Suzanne asks Betty.

Betty lights another cigarette, confesses that she doesn’t know if she can go through with her plan. “Suppose he’s drunk, and just laughs me off?”

“No, he won’t! He might be a grubby old savage, but he’s nobody’s fool. Sis, it’s your God-given duty to march down there and restore him to civilization.” She pauses to adjust the angel atop their tree, and adds, “And don’t take ‘maybe’ for an answer. A half-cooked turkey isn’t worth a damn.”

The grubby old savage in question is sitting at his dining room table drinking beer, listening to an Eagles’ CD, feeling old and tired and superfluous, like the Ghost of Christmas Past, which he kind of resembles, what with his mop of untrimmed hair and beard, his mismatched bedroom slippers, and an old wool watch cap speckled with lint dingleberries atop his shiny pate.

“Well, the kids scooped up their loot and skedaddled,” he tells his cat. “Hell, I can’t blame them – I thought my Granny owned a toy store, too.” But he doesn’t pursue the analogy: his Granny lived until she died with his brother’s family, and never woke up at 3 a.m. so goddamn lonely she could cry.

“You know, Miss Hot Pants, maybe I oughta take Glenn Frey’s advice: ‘Come down from my fences and let someone love me’.” And, he thinks, it doesn’t take an Einstein to figure out who that “someone” might be. Despite his oft-professed love of freedom, he’s forced by his loneliness to conclude that perhaps a tiny bit of domesticity – just a tad, mind you – wouldn’t kill him. This admission so unsettles him, that he goes to the refrigerator for another can of nerve-steadier.

Betty walks down the starlit road, a gift-wrapped twelve-pack of jockey shorts under her arm. The bells of the local church chime a merry carillon, which she considers a good omen. All day, she has practiced various phrasings of her proposal, tried out on Suzanne the words that will hopefully open first his door, and then Sean’s heart. Actually, she expects to be gently rebuffed (if he’s sober), or gruffly dismissed (if he’s not). Praying for the “open sesame” phrase that she needs, Betty crosses herself and Sean’s porch to knock on his door.

In a brief cleansing frenzy before they left, Sean’s daughters rendered the downstairs at least halfway presentable, and upon answering Betty’s knock, he finally lets her in. “Merry Christmas,” he says, with a half-tipsy grin.

“Same to you,” she replies, with outspread arms. “Come here, you old Scrooge, and give me a Christmas hug!” she orders, sweetly but firmly.

Caught off guard, Sean awkwardly complies, stepping back in a bit of a fluster.

“Here’s a little something for a very bad boy,” she twits, handing him his gift. “Santa must’ve ran out of coal and took pity on you.”

Sean accepts it with thanks, lays it aside unopened, and hands her a $3 yard sale sweater he has gift-wrapped in a comic strip page from the Sunday paper. “Santa must’ve had too much egg nog,” he jokes, “he left gifts for you and Suzanne under my tree by mistake.”

Betty oohs and ahhs, thanks him “evah so much”, pronounces him a perfect sweetie, and opens her present. She unfolds it, holds it against her chest (ignoring a mustard stain), and judges it just her size, thank you/thank you/thank you, gives him an um/um/um big kiss.

To his happy surprise, Sean discovers that his lips have retained muscle memory of that long-unused amatory skill, and his ardent response fulfills Betty’s giddiest expectations.

A sleeve in each hand, she loops the sweater around his back; with a triumphant smile, draws him close; chides him for his roguish ways, his disordered lifestyle.

“It just won’t do, Sean, not a bit, your rattling around this big, messy house alone,” she announces, nodding emphatically to bolster her assertion. “It’s high time, I think, for you to admit the obvious: You need a woman to set you straight.”

He looks down at Miss No-Name, who offers no opinion. He looks into Betty’s open, honest, caring face; he recalls his daughters’ worried expressions as they left, their voiced concern over his well-being. Says he, “You’re probably right.”

She tightens the noo… uh… sweater, waits expectantly.

“Would you care to try?” he finally asks.

“I might as well,” she decides, “if you’ll have me.”

And since his momma never raised no fools, he tells her yes.

No Comments