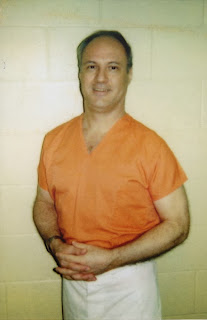

By Michael Lambrix

To read Part 6, click here

Whether it was the almost guttural rumbling of the diesel generator or that unmistakable sulfuric smell of the exhaust, or the combination of both as I struggled to sleep through it on that chilly late fall morning, I don’t know. But there I was at the edge of that abyss between sleep and consciousness and caught in that moment between time and eternity. I found myself tangled in the perception of the past, and what once was new became a prophetic omen of what my life would be, and in that moment I discovered that redemption is a mirror we all look upon.

Each Wednesday, for as long as I can remember, the same perverse ritual played itself out as a reminder to all of us here that we are caught in a perpetual state of limbo between life and death. Each day that passes brings us one step closer to that judicially imposed fate. We are condemned to death and if we ever did dare to forget that, the generator served as a not-so-subtle reminder.

Now it seems like a lifetime ago since I was first housed on that north side of what was then known as “R-Wing” (since then re-lettered as G-Wing for reasons I suppose most of us will never know). But merely changing the identifying letter that hangs above that solid steel door opening on to what was then one of four wings at Florida State Prison that housed us condemned to die in the years before they built the “new” unit of Union Correctional won’t change what lies beyond. Upon entering, one steps into a hell that only the malignant mind of men could ever manifest into reality.

It was late in the summer and I was coming off disciplinary confinement when I was moved over to an empty cell on R-Wing, placed about half way down the tier on the second floor. I was told by the guys around me that it was a quiet floor and a number of the guys made it clear they wanted it to stay that way. I had no problem with that, as the floor I was on had gotten wide open with radios and TVs blasting both night and day and more than a number of the guys yelling to each other so they could be heard above the noise and it never seemed to stop. Now, a little quiet would be welcome.

I moved to the floor on a Friday morning and it took the better part of that weekend to put my property up and arrange my new cell. Only recently were we given large steel footlockers to store all our personal property in. Prior to that, we pretty much just piled the numerous cardboard boxes containing what we called our own in any manner we liked and they left us alone. But the administration claimed the fire marshal warned the boxes were a hazard and had to go.

It was just as well, as the boxes were magnets to the infinite number of both cockroaches and rodents that infested the death row wings. At least with steel locker, it was a little harder for them to get in and out, although it didn’t take too long before they found their ways.

By early that following week I was getting to know the guys I now lived amongst. Funny how that is, every wing on the floor you are housed on seemed to have its own different set of personalities. This particular floor was known to many as the celebrity floor, as it housed a few of the more notorious death row prisoners, such as my new neighbor, Ted Bundy.

While most of those on this particular floor were there by choice, each patiently waiting for a cell to open then requesting to be placed in it as they wanted to be housed on a quiet floor, both me and Ted had no choice. I was placed there for no reason but luck of the draw—when my time in lock-up (disciplinary confinement) was up, it was the only cell open and for Ted, they just liked to keep him on the second floor near the officers’ quarter deck so that when the occasional “four group” of politicians or judges would come through, they could be paraded down the outer catwalk and get their peek at “Bundy.” Most of the time we would know when a tour group was coming and when we heard that outer catwalk door open, we would quickly throw on our headphones and pretend to watch TV as none of us cared to be their entertainment.

At first I didn’t know what to make of it when I realized that I was suddenly housed next door to Ted. In the few years that I had been on death row, I was previously always housed on what was then known as “S-wing,” which was one wing up toward the front of where I now was, but in many ways a whole other world away.

Like everyone else, I had heard of him. And for a good reason he didn’t exactly go out of his way to reach out to those he didn’t know, as too many even in our own little world liked to throw their stones…even those cast down together into this cesspool of the system. I was already aware of how doing time was about being part of a micro-community of various clichés, each of us becoming part of our own little group.

But it didn’t take too long before I found myself standing up at the front of my new cell talking to Ted around that concrete wall that separated us. As coincidence would have it, we shared a lot of common ground, especially when I mentioned that I was born and raised out on the west coast and that Northern California would always be the only place I would truly call “home.”

As the conversation carried on, he had asked if my family still lived out there, but they didn’t, at least not any relatives that mattered. After my parents divorced, when I was still too young to remember, my father gained sole custody of me and my six siblings and then remarried and we gained three more. It was anything but an amicable divorce, and we never were allowed to get to know our mother.

But as I explained the family dynamics, I pulled out a picture of me with my mother and stepfather taken when I finally did get to know them when I was 22. I guess the snow outside the window gave it away, but Ted quickly noticed that detail and commented that he had never seen the snow like that around San Francisco and I then explained that my mom didn’t live in California, as she had moved to Utah and I spent the winter of ’81-’82 with them outside of Salt Lake City.

That caught his attention and after that I couldn’t have shut him up if I had wanted to. For the rest of the evening and into the night he talked about his own time outside of Salt Lake City and as we talked we realized my mom lived only a few blocks from where his mom lived… small world. As two people will do, when reminiscing about common ground, we went on and on about various places we both knew, although neither of us spent more than a few months there. But it brought us together.

In the following months we grew closer through our common interest in the law. At the time I was barely just beginning to learn (Although at that ripe age of 27 I would have sworn I already knew it all). Now twice as old, I look back and realize I didn’t know half as much as I thought I knew and through Ted’s patience I learned what it took to stay alive.

Most of those around here who consider themselves jailhouse lawyers know only what little they might have read in a few law books and then think they know it all. But as I would quickly come to know, only because my new mentor had the patience to teach me, to truly understand the law you must look beyond what the law says and learn how to creatively apply the concepts. And that’s what makes all the difference.

During the time I was next to Ted I was preparing to have my first “clemency” hearing. It’s one of those things we all go through and back then they would schedule us for clemency review after our initial “direct” appeal of the conviction and sentence of death were completed. Only then, by legal definition, does the capital conviction and sentence of death become “final,” if only by word alone.

But nobody actually would get clemency and we all know it was nothing more than a bad joke, a complete pretense. I was still inexcusably naïve, but Ted’s tutorage enlightened me and I dare say that if not for that coincidence of being his neighbor at that particular time in my so-called life, I would have been dead many years ago.

Back at that time, Florida had only recently established a state-funded agency with the statutory responsibility of representing those sentenced to death. But like most else in our “justice” system the creation of this agency was really nothing more than a political pretense never actually intended to accommodate our ability to meaningfully challenge our conviction, but instead existed only to facilitate the greater purpose of expediting executions.

A few years earlier as then Florida Governor “Bloody Bob” Graham aggressively began to push for executions, at the time heading the country in the number put to death, the biggest obstacle was the complete absence of any organized legal agency willing to represent those who faced imminent execution. Repeatedly, lawyers would be assigned only at that last moment and then the courts would be forced to grant a stay of execution until the newly assigned lawyers could familiarize themselves with the case.

In 1985, Governor Graham and then Florida Attorney General Jim Smith joined forces to push through legislative action to create a state agency exclusively responsible for the representation of all death-sentenced prisoners. They believed by doing so, it would speed up executions, as lawyers would no longer be assigned at the last minute. But many others argued that by creating this agency the state would stack the deck by providing only lawyers connected to the state’s own interests.

A compromise was reached in which a former ACLU lawyer known for his advocacy on behalf of death row was hired as the new agency’s first director, and soon after Larry Spalding then hand-picked his own staff. This small group of dedicated advocates quickly succeeded in all but stopping any further executions in Florida and the politicians did not like that, not at all.

For those of us on the Row, it gave us hope. We knew only too well that the insidious politics of death manipulated the process from the very day we were arrested to that final day when we would face execution. Anybody who thinks our judicial system is “fair” has never looked into how the law really works. And with the agency exclusively responsible for representing all those sentenced to death now at the mercy of politically motivated legislative funding, it didn’t take long before the conservative, pro-death politicians in Florida realized that by simply denying the agency adequate funding they would render the work meaningless while still technically complying with the judicial mandate of, at least by statutory definition, providing the necessary legal representation to carry out more executions.

At the time, I had already waited over a year for a lawyer to be assigned to my case, but because of the inadequate funding of the agency, none were available. For the entire Death Row population quickly approached 300, the Florida legislature provided only enough money to hire 3 staff lawyers. It was an impossible job, but they remain committed.

Fortunately, with Ted as my neighbor, I received assistance not available to others, and through his guidance I was able to file the necessary motions requesting assignment of what is known as initial-review collateral counsel. Although none were available, it still built up the record and although like many others who were forced to pursue their initial post-conviction review through such a deliberately corrupted process, at least I was able to get my attempts to have collateral counsel assigned to my case into the permanent record, and although as intended, I was deprived of my meaningful opportunity to pursue this crucial collateral review, thanks to Ted’s assistance, that foundation was laid long ago.

It only took our Supreme Court another 25 years to finally recognize the same constitutional concept that Ted walked me through so long ago—that fundamental fairness and “due process” required the states to provide competent and “effective” assistance of initial-review collateral counsel and if actions attributable to the states deprived a prisoner of that meaningful opportunity to pursue the necessary post-conviction review, then an equitable remedy must be made available. See Martinez v Ryan, 132 Sect. 1309 (2012).

I would say that Ted is probably rolling over in his grave and smiling at all this, but I know he was never buried. It was his choice to be cremated and have his ashes spread in the Cascade Mountains, where he called home.

Perhaps this is one of the lessons I had to learn in those early years when I first came to Death Row. I shared many preconceived opinions that most in our society would. Because of what I heard of Ted Bundy, I had expectations that soon proved to be an illusion. Often over the years I have struggled with the judgments we make of others around us, only too quickly forgetting that while we go through our lives throwing stones, we become blissfully oblivious to the stones being thrown at us.

Maybe we will want to call him a monster, and few would deny the evil that existed within him. But when I look to those who gather outside on the day of yet another state-sanctioned execution, I now see that same evil on the face of those who all but foam at their mouth while screaming for the death of one of us here. That doesn’t make these people evil, per se, but merely reminds me of a truth I came to know only by being condemned to death: that both good and evil do simultaneously co-exist within each of us and only by making that conscious effort every day to rise above it, can each of us truly hold any hope of not succumbing to it and becoming that monster ourselves.

Being condemned to death is often ultimately defined by the evolution of our spiritual consciousness. I know all too well that there will be many who will want to throw stones at me because I dared to find a redeeming quality in someone they see as a monster. And as those stones might fall upon me, I will wear those scars well, knowing that it is easy to see only the evil within another, but by becoming a stronger man I can still find the good. And despite being cast down into the bowels of a hell, that ability, and even more importantly, that willingness to find good in those around me has made me a better man.

It was around that same time that the hands of fate brought me into contact with another man I knew long before I came to Death Row. The thing about this micro-community we are cast down into is that it really is a very segregated world. Unless you get regular visits—which very few ever do—you’re never around any others but those housed on your particular floor.

Not long after I came to be housed on R-wing, I went out to the recreation yard and recognized a familiar face. I knew him as Tony (Anthony Bertolotti) and back in 1982 we did time together at Baker Correctional, a state prison up near the Georgia state line. I was the clerk for the vocational school program at Baker while Tony worked as a staff barber. Because both of us were assigned “administrative” jobs, we were both housed in the same dormitory, just a few cells apart. Although he wasn’t someone I hung out with back then that small measure of familiarity created a bond and we would talk for hours about those we once knew.

But Tony wasn’t doing so well. Like me, he had been sentenced to death in 1984 and in just those few years he had already given up hope. That was common, but few actually acted upon it. Tony was one of these few, and at the time he was beginning to push to force the governor to sing his death warrant, which he did subsequently succeed and became one of Florida’s first “voluntary” executions. His only perception of reality around him was cast within a dark cloud, so dark no sunshine could appear. And his own escape from that reality was to pursue that myth they call “finality” by bringing about his own death.

So, there I lay that early fall morning. If at that moment I were to get out of that bunk and stand at the front of my cell, I know that I could look straight outward a couple hundred feet in the distance and clearly see that grass-green building we know as the generator plant, which stood just on the other side of the rows of fencing crowned with even more rows of glistening razor wire. And then by looking off to my right of the wing, immediately adjacent to the one in which I was housed, I could see the windows on the first floor that I knew would be where the witnesses gathered when they carried out each execution.

Although I knew these sights well, as well as the sound and smell of that generator plant that they cranked up every Wednesday to test the electric chair (long after that electric chair was banished and replaced with lethal injection they continued to crank that generator up), instead I chose to lay there in my bunk with my eyes closed and manipulate those sounds and smell into a memory that didn’t drag me down and even bring about a smile.

There was another time in my life when I would be awoken to the sound and smell of a diesel generator, and it too was all about how I chose to perceive it. When I was 15 years old I left home and found the only kind of job a homeless teen could by working with a traveling carnival, mostly around the Chicago area.

Most people might find it unimaginable that a “child” of 15 would be out on his own, but if they knew what life was like at “home” then they might understand why I can look back at that time and find a measure of happiness I seldom experienced in my so-called life. Leaving home as a teenager was not so much a choice, but a means of survival. I wasn’t alone—all my siblings also dropped out of school and left “home” at their earliest opportunity and so at least for me, finding work with a traveling carnival was a blessing, as the alternative was to live on the streets.

In the spring of 1976, shortly before my 16th birthday, I left Florida with a carnival that had worked the local county fair, assured I would find work when they joined another show in the Chicago area. But it didn’t work out that way as it was still too cold for the carnivals to set up. For the first few weeks I had no work and no place to stay. I had no money for food and tried to find a meal at a Salvation Army kitchen only to be interrogated by the volunteers who insisted they had to send me “home.” I left without being fed and never again went to a shelter.

At that time in my life, while most my age were just starting High School, living on the streets and sleeping on layers of cardboard boxes was better than being forced to return home and once the weather warmed up and the carnival could set up, I found work at a game concession paying twenty dollars a day—and the boss allowed me to sleep at night in the tent.

Each morning when it was time to start opening the show, that generator would crank up and first that distinctive machinery rumbling would be heard followed only a moment later by that sulfuric smell of the diesel exhaust, and when I closed my eyes that same sound and smell still made me smile, is just like waking up to that job I found at 15, it brought me, at least mentally, to a safer place that anything I knew of as “home” and the freedom of being on my own.

Now when I hear (and smell) that generator just as I did the first time on that chilly early fall morning of 1985, I am reminded that whether it be man or machine, it’s all in how we choose to see it, as the evil within anyone or anything can only exist if one chooses to focus on that. But just as I learned from coming to actually know the person that was Ted Bundy, and finding that although evil acts can undoubtedly be attributed to him, he was not all evil, but also possessed that measure of a man within that had good, it is also true for the many years that would follow as if I’ve learned nothing else through this experience, it is that this evil that exists within the manifestation of the men (and women) around us exists on both sides of these bars and no matter what the source of evil might be, it can only touch and tarnish my own soul if I allow it to.

My lesson so long ago was that redemption (especially that of self) is a mirror that we look into and it’s the image that looks back upon us that ultimately defines who we are and more importantly, who we become. I consider myself blessed to have been around those that society has labeled as “monsters” as it has endowed upon me the strength to find something good within each. And I know that as long as I can find a redeemable quality in all others, there will still be the hope that others will find something redeemable within me.

|

| Michael Lambrix was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017 |

No Comments

Unknown

February 10, 2016 at 4:49 amMike …you are the best. I dont know how you manage to keep cool and even your sanity under these adverse conditions. All your posts are exceptional, and your book is gripping to the end. You can start writing another because no lethal injection is in your future….my prayers are usually answered. This would be total injustice. One love my friend, and keep on writing.