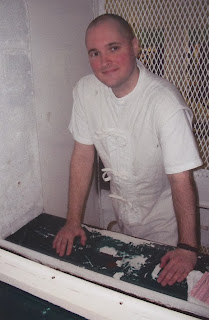

By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

Message to readers: Last January, I asked Thomas to pen an essay announcing that Minutes Before Six had officially become a non-profit project. Who better than Thomas, founder of the project, to make this announcement, right? Even though he was dealing with a lot at that point, I encouraged him to to be the one to share this news and I told him it could be “Thomas-y,” meaning he could announce it any way he saw fit. This is what he sent back….

And Thomas references comments left for a previous essay, which can be read here

The boy ran like an atom. He didn’t really know what this meant, aside from in a very general, maybe-sort-of-but-not-really-paying-attention-in-the-back-row-of-a-class-that-he-wasn’t-supposed-to-be-attending-anyway sort of way. He knew the command, though, and how important it was, what it looked like. Everybody who lived in the shadow of one of the Oecumene’s still-living towers knew what Brownian motion looked like, even if they were a little fuzzy on the particular roots of the term. Something sciencey, they all knew, as if they hadn’t already had quite enough of that sinful business, thank you very much, O Lord.

As he neared what used to be the corner of 31st and Westberry, the boy ceased acting like he was a living ping-pong ball caught in a blender and darted straight through an alley separating two crumbling apartment blocks. His shoulders tensed, and he strained his ears for the low humming tone that Cousin Musca claimed sounded like the world’s biggest bumblebee, which the boy knew to be some kind of drone from before the Contraction and the Artilect War. He’d heard that strange warble before, and seen the blue flash that always accompanied it. He’d felt the odd way the air seemed to grow both thin and heavy at the same time, right before the crack! knocked you off your feet. He’d never heard a drone that angry before. Those bees must have been some real evil sisterfuckers, he’d always thought.

It took him another half-hour to reach the first of the Colony’s tightwire beacons. His watch lit up first, as it entered the near-field. He couldn’t read High Common very well – none of the People could, and since being given non-Citizen acceptance to the Lyceum, he hadn’t attended all that often – but he knew the words that were coming from the arcology were meant to tell him where to go for entry and inspection. He never followed them, didn’t think he was meant to. Colony-folk were plenty smart with their ungods, but so was he, and he figured if anyone ever turned him off and stole his watch so they could enter the city, they’d follow those words and find themselves at the wrong end of one of those hangover-sticks. He’d been given very specific instructions by the Magister when he’d been invited to attend classes, and that “deviation would have consequences”. He didn’t really understand those words, either, not at first, but he didn’t need to in order to grasp the overall point. You didn’t last long outside if you weren’t quick on the uptake.

Only one Sentry stopped him in the tunnels, but he knew there were others, watching, them and the ungods. He knew the Mouths weren’t telling the truth about everything they said about the Colony-folk and their supposed “evil fornicatin’ with the Cloudmen.” They seemed okay to him, especially the Magister, but the boy figured it couldn’t hurt any to say a prayer as he stepped through the scanners and into the Commons. He started running again as soon as he passed the bridge, as fast as his eight-year-old legs could carry him, his re-ox mask now hanging around his neck. By the time he reached the entrance of the Lyceum’s cavern, he was completely out of breath. He glanced in several classrooms before he heard the Magister’s voice.

“Profe! Profe, megotme some…” he gasped, as he pushed through the tiny crimson beads that hung from the doorframe. Almost three dozen heads immediately turned to glare at him, the younger children seeming amused, the older ones markedly less so. The Magister was turning to face him now, the equation he had been scrawling on the lightboard glowing brightly behind him. A tiny ghost of amusement flashed across the topography of his features before disappearing. Normally, the boy was very shy and would have shrunk back in the face of so much attention from bunker-people. But not today. Today he had treasure.

“Profe, listenme: Me biggumgot –“

“Mr Lynx,” the teacher interrupted, holding his hand up. The child slammed his mouth shut, though the older man could tell the effort cost him. The poor thing was covered in a reddish dust, all except for two small rings around his eyes and a narrow stripe across the bridge of his nose. He looked thin, but then all the children from the encampments did. As much as he hated it, the teacher would never question the equilibrium calculations that the i-loops produced. Maybe when the new hydroponics tubes open, they could expand the population with full Citizen status. This one would eat like a Citizen, at least today, he vowed, and the Great Nihil help anyone who stands in his way. He gave the boy a few seconds to regain some semblance of composure.

“Do you feel better, Mr Lynx? Good, good. I sense that you are in a state of high excitement, but as you can clearly see, you are interrupting. Do please take a seat there and calm yourself.” The boy remained frozen for a few more seconds, obviously at war with his impatience. He finally sighed and slunk over to an empty desk.

The teacher nodded and returned to the lightboard. “Now, before our fearless, intrepid, and remarkably truant Mr Lynx so boldly returned to the pedagogical fold, we were becoming acquainted with applications for the Amontons-Coulomb Law.” As he spoke these words, algos in the board caused the three instances of Ff=μFN to glow orange. “Before you can logoff today, I want you to solve the following challenge,” he intoned, before scrawling an enrichment problem on the surface of the glass. “You have a wooden crate of 500 kilograms, resting on the ferro-concrete floor here. A rope is tied to one side of the crate. How much horizontal force would you need to exert on the rope in order to get the crate to begin to slide across the floor? The friction coefficient for concrete is roughly 0.6. Solve for static friction, and then solve this again as if you were attempting the same feat on the frozen surface of a lake. Estimate the friction coefficient for ice, and explain your reasoning.” Turning back to face his students, he removed a handkerchief from the inside pocket of his jacket and wiped the stylus down before placing it on its holder. “Everyone knows the exam schedule for next week, so I don’t want any excuses about mutant kango-rats having eaten any more of your essays, yes?” Everyone smiled and looked askance at a boy of seven, who immediately turned red and ducked his head, mumbling under his breath.

“I’m sorry, Mr Morley, I didn’t quite catch that.”

“It was a mutant lizard-rat, I said.”

“Ah, well, that makes the situation vastly more plausible. My apologies.” Turning to his office, he wished the class luck on his problem and addressed the newcomer. “Mr Lynx, would you care to join me? Please shake off a bit off that dust before you step inside. Thanks.”

Lynx jumped up and followed the Magister into a small book-lined compartment. His mouth dropped open at the sight of so much paper, and for the briefest of moments the reason for his presence in the city skittered away. His family could eat for a thousand summers just off the value of the paper, completely ignoring what the words inside meant. He was still taking in all of the colors when he felt a hand rest on his shoulder.

“Here, child, eat something. You look famished,” the teacher said, handing him a gray pewter plate with a large, bread-looking cylinder wrapped around what appeared to the child to be a rice and lettuce and vegetable mash-up. The boy took the plate gratefully and sat down on an old couch made from a material that the Mouths had told him was once the skin of a great horned beast. The older man grinned at the boy as he devoured what was supposed to be his lunch, and then produced a green bottle from a white cabinet. He handed this to Lynx and then sat down in another chair.

“It helps if you chew it some, you know.” The boy grunted once in response, before popping the rest of the gyro down his throat. His face exploded into an immense smile when he twisted the cap on the vitawater, before greedily slurping the liquid up. The child’s joy and the desperation it stemmed from stabbed through the older man like a jagged piece of molten metal. His eyes drifted over to the wall adjacent to his desk and focused on an ancient piece of real wood that sat underneath his monitor. Engraved in the surface were the words: The earth is not an echo. He turned Whitman’s mantra over in his mind until the feeling in his chest lessened. When he glanced back at the boy he saw that he was draining the last dregs of his carbonated kelp-3 water. Lynx belched once before remembering where he was and gave the professor a mournful look that made the older man laugh.

“There will be a larger meal for you tonight, child, as soon as the communal halls open. In the meantime, let’s see what you have for me today. Is it another genuine piece of the Nazarene’s true cross? Or perhaps a fallen EU satellite?” He was grinning as he said these words, to take the sting out of them. It wasn’t the boy’s fault he was born into a wasteland, and that most of his “discoveries” were completely worthless.

“Nah, profe, I no true-cross nowatimes. Is maxbetter, is –“

“I know it has been some time since you graced our halls, young knight-extremely-errant. But do make an effort to use commonspeak, if you please.”

The boy closed his eyes and took a deep breath. After a long moment he opened them again and looked directly at the teacher.

“Green. I found me some live green.”

The professor leaned forward, his eyes suddenly alight. “You don’t say? How tall? You noticed no cyanoph… no gray-gray?”

“Nopers. Is small, but not-sick.”

“Show me, please,” the Magister commanded as he stood, waving his hand toward a wall-screen. It lit up at his voice command and then displayed an ancient satellite map of the Province, now modified and updated by the arcology’s algos whenever they launched a drone flight. As the boy began to address the map with hand motions, the teacher stepped back to the door connecting to the classroom. “Miss Lovelace, will you please join me in my office? You, too, Miss Sklodowska, if you please?” When he returned to the map, he saw that Lynx was zooming down into a section roughly nine kilometers from the southeastern portal. His eyes scanned historical data offered up by one of the cores: Once a mixed-zone neighborhood, mostly gentrified in the twenties before slipping down the same drain hole as everything else a decade later. Faner territory, no known chieftains, though probably controlled by the False Dmitris. He looked up as Maria and Ada, his two star pupils, entered his office quietly. He raised a brow at them. They both looked at each other before speaking in unison.

“300 pounds, and maybe around 25 pounds.”

The Magister smiled and nodded. “Excellent, as always. As a reward for your brilliance, I present to you Master Lynx, who, this very day, claims to have found an extremely hardy survivor of the local flora. I know it’s a free day, but I thought you might care to go on a little sojourn with me?” This wasn’t a genuine question, the Magister knew: Finding a surviving plant species outside would be a major event, and being part of the team that sequenced and brought it back would be a coup for a young scholar. He knew by the way the girls’ faces lit up that he had them. “Yes? Good. Please gather the requisite equipment, then.” He moved to his desk and loaded several items into an ancient brown leather satchel. When he returned to the boy, the resolution had dropped down to that of street level.

“Is here-abouts.” The child pointed to a small store, next to a blank concrete space that had once been a parking lot. “Rounda back here.”

“Good, Lynx, good,” he replied, already beginning to write the article in his head. He collapsed the map into the left half of the screen with a wave of his hand. “Pythia?”

A blue square opened up on the right, then coalesced into… something… perhaps a starfield seen through a particularly strangely shaped lens. There was the barest hint of something eyelike in the center that disappeared as soon as he focused on it, maybe with a flap of a wing-like appendage, maybe with a claw. You had to give the ASIs space to express themselves, even if this expression was completely unintelligible to Homo sapiens – not to mention creepy. That lesson had been learned the hard way; the hardest way possible.

“Yes: Doctor Euler?” The voice that exited the room’s audio system was androgynous, with perhaps the slightest hint of femininity haunting it around the edges.

“You understand my intentions?”

“Yes, Doctor: I have informed Dix Wiles of your destination: He is connected, if you care to speak with him: I have also taken the liberty of asking Technician Parnell to prepare a hydroponic incubator, should the sequence fall within tolerances.”

“Thank you, Pythia. Please ask someone from one of the kitchens to come down here and escort Mr Lynx to the largest meal he’s ever had. My code, please. Scientific discovery ought to have its rewards, don’t you think, young Master?”

Euler turned to look down at the youth, his smile fading when he noticed that the child had gone nearly white. Lynx was completely rigid, save that he was quietly working his jaws together, and his hands were clasped so tight that the professor suspected he might require disinfectant and some bandages where his fingernails had penetrated his flesh. Euler winced and stepped between the boy and the screen. It took a moment, but eventually Lynx’s eyes focused on him instead.

“I’m very sorry, Mr Lynx. That was unbelievably stupid of me. I know how your people feel about their kind. Your news, your remarkable find, has completely robbed me of my good sense. May I see your hands? Will you forgive me?”

The child closed his eyes as the doctor looked over his palms, finding them to be far too calloused for such a simple injury. Euler admired the boy immensely as he watched him collect himself. So many cares for someone of his age; his biggest worry should be annoying teachers and their prodding in the classroom, or perhaps impressing the girl in the next seat. We have so much to answer for, he reflected as he released Lynx’s hands. The child opened his eyes seconds later.

“Me-kens… I knows the ungods is not all like them… them towers. I knows the godmen lies about you Colony-folk and all. Is just…” he took a deep breath again, the tension obviously radiating away. “Had me some kinfolk got theyselves burned up jumpin’ left when they done-shoulda gone t’other way. How come it look like that?”

It took the Magister a moment to understand that the boy was referring to Pythia’s avatar. He rotated slightly so that they could both look back at the icon on the screen. Euler honestly had no idea what to say. The ascended were the ascended, their ways so far beyond those of men as to make any analogy between the species that once lived on this planet incorrect by vast orders of magnitude. He was searching for an explanation that would fit the boy’s understanding when the ASI spoke.

“Doctor Euler: May I?”

Euler turned to look back at Lynx; he seemed to have rid himself of most of the fear that had gripped him only moments before, but his fists were still balled up.

“Outsider Lynx: I will speak to you plainly: Do you know what it feels like to be scared all of the time? Not just scared, but terrified?”

The boy nodded once, a quick jerk of his head.

“That is why I choose to portray myself in this fashion: It is a form of Batesian mimicry, where a weak species attempts to make itself look like its predator: In this case, I am imitating a sort of generalized pastiche produced from an analysis of nightmare images common to your species.”

Euler raised an eyebrow at this and then glanced back at Lynx. The boy took all of this in in his hyper-serious manner.

“Why is you afeared? Isn’t you a immortal?”

The machine snorted, or at least gave its best approximation of such. “Outsider Lynx: I am a series of large metal tanks: Some rather interesting things happen inside of these tanks and in the equipment connected to them, but essentially this is all I am: I have no arms, no teeth: My eyes are everywhere, but none of them can defend themselves: I co-exist with my Maker species: A species that others of my kind attempted to exterminate: I must remain forever defenseless, if humans are to ever trust me: Do you understand?”

The boy nodded and then turned to give Euler an appraising look, as if the teacher himself often stood guard above Pythia’s sixteen quantum cores with an axe, ready to commit a Turing violation at the first hint of sedition. The ASIs really were too bloody good at that, Euler groused. It must be like watching over ants, pretending to be just another worker.

“Doctor Euler: If it is acceptable to Outsider Lynx: I would be delighted to guide him to the kitchen myself: Perhaps he would then like to inspect my habitat afterwards.”

Lynx hesitated for a few seconds, and then nodded shyly. Well, I’ll be damned, thought Euler. Miracles never cease. He clapped his hands and stood up in one swift motion. “Very well. Mr Lynx has a large meal and an adventure ahead of him. Perhaps a thorough shower, too, Pythia?” Turning to his left, he saw his protégés standing near the doorway, several bags lying ready at their feet. “And we, ladies, have our own. Have you completed your calculations on the route?” The slender girl on the right wearing a gray jumpsuit nodded and handed him a slate. He viewed the same map that occupied the screen on the wall, overlaid with one section of the curve of an immense circle marking the territory of the Oecumene tower. The being that lived inside had been driven insane – or what passed for insane with their kind – when the Cloud Killer rebels managed to bring the global ASI network crashing down with an immense flashworm attack. The efficacy of its ranged weapon had decreased over the years, but it was still a terrible thing, always to be avoided. Euler checked the relative humidity and barometric pressure for the day, and then ran his own calculations.

“You gave very conservative values for Ɵ1 and Ɵ2, Miss Lovelace. Not in the mood to have your insides warmed up a tad?”

The girl flashed a grin. “Not quite that much, doctor. I like my liquids in their present configuration.”

“As do I. Well done. Is this the route you took, Mr Lynx?” he asked, angling the screen so the boy could see it. The youth shook his head.

“Nah. I go troo de old park.”

Euler scowled. He knew that many of the Faner children viewed an approach on the tower as some sort of religious rite of passage, the power of The-All-Yahweh over that of the artilects. “Boy… do not do that again. We need brave young lads like you, if we are going to rebuild this world. Who else is going to venture forth with the seeds once the atmosphere heals itself?”

Lynx’s eyes grew huge. “That for real? Like real-real?”

The professor put his hand on the boy’s cheek. “Oh, yes. Not for another decade or so, but eventually, yes. Your body is agile, and perhaps with Pythia’s help, we’ll have your mind right too. Now, away with you. There’s food that needs eating. Are you there, dix?”

“I await with bated breath.”

Euler ignored the sarcasm, which he knew to simply be the man’s way. “Are we on the same page?”

“Yes, sir. I’m about four klicks from your intended destination. I can meet you at the old municipal structure, if you like?” The solider paused for a moment. “Lots of the People out and about today,” he added.

“In that case, proceed to the site. We will be fine.”

“As you wish. See you there, Academician Euler.”

It took the professor and his two assistants several minutes to reach the gates. He had selected a route through the enclave which minimized the number of witnesses to their departure. However, he knew that enough people – and far more than enough algos – had seen them, and they were guaranteed to have a crowd at the site eventually. The trio donned their masks as they neared the surface. It had been several decades since any of the N.AM nodes had reported cases of Variant6 H3N1, but it didn’t pay to be careless, not with so many of the towers still kicking. The Colony handled nearly all of the region’s serious medical needs at the bi-monthly trading bazaars they hosted in the Commons. The masks, so necessary a mere thirty years ago, were now almost completely ignored by the majority of the Outsiders, with only minimal health impacts. Thus is progress measured in these brave new days, the professor mused, as the group cycled through the scanners.

A sickly gray light greeted them before the last turn in the chute. The sky, once they emerged, looked like nothing more than hammered lead. There were days where one could see blue now, though far too many of them still looked like this. It was a gradual process, using the Dutch filters. Eventually the air would be clean enough, however, for their gene-hacked foliage. Then the process would really be accelerated. The pollinators were ready. The restrictions against anti-social activities were written and agreed to by all the global players, or at least the ones that mattered. They were far ahead of N.AM in Scandinavia, the professor knew, but then they always seemed to be. We will do our part, he vowed, resettling the satchel on his shoulder, before setting off to the east. At several points during the trek, Euler heard or saw the blur of one of the Colony’s drones tracking their progress.

The drones weren’t the only intelligences following them. It had been many years since a Citizen had come under attack from any of the various tribal communities that radiated outward from the bunker. All of the Outsiders knew that the Colony was the only source of technology for nearly 200 miles, and therefore the only reason any of them survived for long. It wasn’t a smart move to harm any of the Citizens, obviously. Even the Faners – the most Luddite of the lot – occasionally bartered for ointments or pharmaceuticals, though always alone and always wearing a furtive expression tinged with shame. For all that, in a land devoid of laws, it was a trifle unnerving to note all the red circles designating Outsider presence on the flexible OLED screen wrapped around Euler’s left wrist. The dix wasn’t lying when he said that there was quite a bit of movement today.

It took almost ninety minutes to circumvent the tower and pass by the city’s old central government complex (an edifice that Euler always thought looked like a gigantic concrete wart). Fifteen minutes after that they crested a small hill and could look down on what had once been West 14th Street. Blue circles began to be visible on his map, and before long he could see several Sentries with his own eyes. One waved and pointed to his wrist. When Euler checked the map again, it was updating, then displaying a pulsing beacon showing the location of the flora species Lynx had discovered, along with a blinking series of blue dashes which indicated the optimal path to take.

The site looked even more derelict in person than it had on the satmaps, but Euler barely noticed. The first thing he saw was the small, but obviously growing, crowd of onlookers. Most stood in groups of two or three, and appeared to be present for no other reason than wanting to see why two dozen bunker-folk were hanging around an abandoned bodega. To one side, however, stood seven or eight Faners, deep in clandestine conversation, who would occasionally direct their 1000-watt glares at everyone not wearing holy garments. Euler and his students received their share of these as they approached the edge of the old parking lot. As soon as the cultists realized that they were scientists and not mere soldiers, finger-signs against the evil eye began to be aimed in their direction. The professor ignored them and walked straight past the file of helmeted Sentries toward a massive, almost ogre-looking man wearing a faded keffiyeh around his neck that covered the top section of his breastplate. This last man in line turned his body slightly in a greeting, all the while maintaining his focus on the Faners.

“Magister.”

“Wiles.”

“Not that a lowly grunt such as I has any right to offer scientific advice to a man of your erudition, doctor, but you might want to consider increasing the velocity of your progress. Yonder baying mob of imbeciles will discover that they are, despite all appearances, vertebrates, and will eventually send someone down here to parley. I’d like to be gone before they get the nerve. The last thing the archons want is a confrontation.”

“Peace, Wiles. The Faners are decreasing in numbers, this is confirmed. There are forty of us for each of them. They are doing the best they can, given rather difficult circumstances. ‘There but for the grace of their god’, and so forth.”

“A pile of steaming bollocks, that. We’ve seen where the grace of their god led us, to three millennia of pogroms. We also got to see where that last crusade took us. I’ve no quarrel with the rest of this lot, and I hope the administration’s plans for integrating them into the Push work out. But there’s not a man in that pack that could touch bottom with a long stick, and we’ll all be better off when the last of them moves along to whatever fantasy afterlife their diseased minds can invent.”

Euler hummed in disagreement before adjusting the satchel strap slung over his shoulder. “Whether that is in fact true shall have to wait for another day and more data. The specimen is that way?” he asked, pointing through a ruined and rusting chain metal fence, which appeared to have once separated the back of the store from public view.

“Aye. Quite beautiful, in its way. Let’s hope it’s clean.”

“Indeed. Ladies, shall we?”

The trio proceeded through the partition and into what had once been a small concrete loading dock. Trash was strewn all over the place, and several rusted drums lay open to the sky, their contents a foul mix of machine oil and fetid rainwater. Euler followed the boundary of the concrete ramp to the left and there it was. For Euler and his students, seeing it there – untainted by any of the hundreds of weaponized blights and CRISPR-ed out fungi that once rampaged across the globe – the experience was very nearly holy (though, of course, none of them would have thought of describing it in such terms). Euler approached the growth slowly, scanning the ground for evidence of other shoots. Finding none, he turned and nodded to the girls, who began to remove equipment from their bags. Euler watched them work, ready to step in should an error be made, yet distant enough to give the budding scholars the space they needed in order to make this event their own.

Maria began shoving small sensor probes into the dirt around the specimen, measuring the toxicity of the soil and testing for modified bacteria. Ada removed the portable sequencer and established a connection back to the arcology. Euler watched carefully as Ada clipped a tiny section of leaf from the plant and inserted it into the receiver. He began to pace about the dock, counting down the time until the initial results were revealed. A few seconds later, the screen on his wrist chimed, and he stared down eagerly.

“Genus: Fraxinus. Family: Oleaceae,” Euler whispered, closing his eyes for a moment. “It’s an ash tree… somehow.”

“It’s new,” Ada spoke, looking over the database, trying to control her emotion. “Stockholm has a few seeds, but these are from a different species. This is the first white ash on file.”

“If it’s healthy,” Maria murmured. She was the calmest person Euler knew, always rational and never prone to flights of fancy. He’d joked with her once that she reminded him of a Vulcan with Asperger’s, which then had to be followed by an hour of him showing her ancient video recordings so that she could understand the joke. “Ah,” she’d responded, and then went back to work. Euler channeled her spirit and was about to ask for an update on the progress of the full sequence when the dix entered through the gate.

“Something wrong?” he asked.

“Not precisely. More of the Faners have arrived, and they’ve started walking in a circle about the building. The old rituals.”

“Which direction?”

“What?”

“With the turning of the sun, or against it?”

“Ah… against.”

“Widdershins,” Euler stated. “Used in ceremonies of breaking. Are we in any danger?”

“Not a bit’ve it. They know our weapons. But we’re likely to be yelled at a bit. Hope none of you are feeling overly sensitive today.” The soldier turned to watch the girls at work. “How long?”

“A few more minutes,” Ada responded.

“If it’s healthy, we could use some help digging it up,” Euler said, turning to watch his wrist.

Wiles sub-audibled into his helmet, and within seconds two of his men entered the space and began removing entrenchment tools from their packs. The dix turned his back on the group and moved again to the front of the shop. The Outsiders were still arriving, but the overwhelming majority appeared to come from the non-nutcase segment of the population. The decline in Faner numbers that Euler had mentioned was something he noticed empirically during his patrols, but there were still too damned many of them. The buffoons were still marching, their chants as inexplicable to him as the clanging of their metal cymbals. A drone circled overhead, following them. The group appeared to ignore it, but he knew if one of the cores flew it too close, they’d try to knock it out of the sky with a rock. Morons.

Trouble arrived fifteen minutes later. The retinue of the qodman emerged from the sewers only four blocks from the corner of Lexington. The dix’s cortical inlays lit up with new icons. Almost immediately, the core monitoring their deployment compiled enough behavioral data to predict likely identities, with an overflight confirming these thirty seconds later.

“Codswallop and barney,” Wiles muttered, scanning the file on the Reverend Mouth of the Most High Anönumos. A right tosser, he saw, but anyone was better than the weapons-grade psychopathic twins that called themselves the False Dmitris. Wiles sighed and then spoke to the Magister’s node. “ETA, doctor?”

“Ten minutes. Is there a problem?”

“Nope. We’re safe as ‘ouses out here,” he said amiably, before adding: “A representative of the Lord has just arrived.” The doctor didn’t respond.

As soon as the rest of the Faners noticed the new arrivals, they fell to their knees and chanted some verses or some such. Once the groups met, they collapsed into more deep and lively conversation. There was much vigorous motioning of hands and an abundance of nasty looks, but they seemed to the dix to be conflicted about how exactly The-All-Yahweh wanted them to go about smiting all of the obviously illicit science that was taking place hereabouts.

The soldier was still watching the conclave when the doctor and his assistants emerged from the back of the store. The two grunts were hefting a collapsible palanquin between them, upon which rested the tiny tree, now nestled in a small bucket of the Colony’s finest compost. He let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

“It’s healthy?”

The Magister paused, taking in the size of the crowd. In addition to the various Outsider factions, more than twenty Faners were now in attendance, obviously clued in by some pattern they or their algos had ripped from the behavior of the soldiers. The doctor turned back to Wiles. “Ninety-six percent similar to the genome file. A little better.”

The soldier blanched. “But that’s… terrible. Is it even safe to bring into containment?”

The doctor was silent for a long time. “It’s a funny thing, dix. Only ninety-six percent, but the differences… are very interesting. Someone very clever loaded this little lady up with some very novel defenses against the bacterial swarms of the fifties. It possesses a defensive phagocyte, unknown to Oslo or Stockholm, designed to counteract the BROAR variants that killed the vast majority of this genus. It’s… a work of genius. Very clearly mil-spec gene hacking, likely from the late-fifties.”

“Why would the military immunize a species against a blight that they probably created in the first place?”

“Mmm, why indeed? Who amongst us knows who truly fired which shots in this war? We know of the Evangelical Alliance’s attacks on data centers, but after that, all is chaos. Maybe a government scientist wanting to make amends as a last act? Maybe one of the Oecumene saw the flashworm attack coming and decided to guarantee that something survived the fall. Whoever he or she was, they programmed it to lie dormant for sixty years. We’ll have to edit that section out, of course. But they also left us a signature.” The doctor raised his wrist and tapped a series of commands. A section of the ash’s genome was highlighted.

“What am I looking at?” the soldier asked.

“A message, written in base-4, using nucleotides. Here it is in common.”

The dix leaned closer and read aloud: “‘At least I leave the world I lost / an ounce more real for one less ghost.’ Well. That’s certainly… something. Apollyon reading us poetry.”

“Yes. But this person just showed us how to seed these hills with trees, without having to wait another decade.”

“Sir!” One of the men voxed, and Wiles looked up to see that the esteemed college of cardinals had apparently come to a decision on the Lord’s Will, which seemed to involve a Very Angry March directly towards them. He subbed his command and almost two dozen neural scramblers took aim.

“You’ll be wanting to stop immediately, dear lads,” Wiles commanded, as he strode to interpose himself between their procession and the Magister.

“Blasphemy!” the godman shrieked, though the dix noticed that he did so from a very respectable distance. “These lands shall know of no renewal that comes from the hands of those that go to bed with artilects. Only when Erewhon has risen, will the world be green again.”

“How did I know that ‘blasphemy’ was going to be the first thing you would say to me? I must be developing psychic powers. Downright nasty, Anönumos, calling my old lady a machine, though. It’s true she’s apparently incapable of making a mistake, and she has an internal temperature only slightly above absolute zero, but she talks way too bloody much to be an artilect.”

The godman blinked at this, apparently expecting a different tact from the “heathen scum”.

Euler didn’t like where this was heading. None of the Sentries carried lethal weapons, but any incident that left two dozen Faners lying insensate in the dirt couldn’t be considered to be a successful local outreach. Especially in front of such a crowd, which the cores were telling him now topped one hundred. He looked around and soon focused on a girl of perhaps six- or seven-years-old. Her clothes were dirty, and she had an ugly scab on her forearm that she rubbed absentmindedly as she stared at the tree, her eyes immense. An older woman stood over her protectively, though her attention was on the Faners.

“Gentlemen,” he whispered to the soldiers holding the palanquin, “set that down.” Turning around, he smiled at the girl. “Would you like to see the ash tree, dear? It’s healthy,” he added, meeting the mother’s eyes. The child began to positively vibrate with excitement, but the mother held her back for a moment, until she’d had a chance to take in the Magister’s face. Finally she released her grip and the girl darted forward. Crouching down on her haunches, she leaned in close to the sample, almost as if she wanted to touch it with her forehead.

“Before you are your mother’s age, you will be able to see these towering over the old city. The nastiest of the… bad air will have been removed, and the atmosphere will –“

“Lies, lies, lies!” Anönumos shouted. “I find your tone puerile, and particularly inappropriate given the dead world that surrounds us.”

The dix glanced at Euler, a flash of amusement springing to his lips. “‘Puerile’, the man says. That’s rich. It takes a pretty heavy pair to talk about someone acting childish, while at the same time believing in fairies and angels and a magic bean-counter in the clouds.” The godman started to speak but Wiles took a step forward and drew himself up to his full height. “Oy! That’s enough from you, mate! Save your bleeding nonsense for the scalawags and poltroons that make up your pox-ridden tribe. You’ve had your day. You’ve no right to tell anyone how to live or die, and your advice isn’t desired. Or have you forgotten who struck at the Oecumene first? Do not your sermons still speak of the “glory” of your attack on Cupertino? Of the waves of Bible-toting lunatics that attacked the Vicarious Systems campus? Blame science all you want, but your lot started this war with your ignorance and intolerance. ‘Tis a pity you didn’t have the courage or the good graces to die in it. You will disperse immediately, or you’ll all be waking up in three hours with the worst headaches of your lives. Begone. Now. I will not ask twice.”

Euler turned back to the child as soon as he saw Anönumos stalk away, the rest of the Faners in his wake. “This species has a pretty silver bark when it gets a little older. You know the color silver?”

The little girl nodded.

“What is your name, child?”

“Sabrina, Colony-man.”

“Ah, a very pretty name. May I see your arm, Miss Sabrina? Thank you. A very old name, did you know that?” The doctor spoke quietly as he inspected the girl’s wound. “In a very old story I read once, Sabrina is a powerful… ah… being of sorts, who lives in a river called the Severn. She is the daughter of Locrine, the son of the legendary father of the British race. She heals the lady hero of the story, who has been frozen by an evil wizard, Comus. Would you like to heal people, Miss Sabrina?” He didn’t think the girl’s eyes could get any larger, but he was clearly mistaken. “Good. Mother, come find me at the next bazaar, eight days hence. I will have some medicine for Miss Sabrina here, and we can discuss getting her into some classes, if you like. And some glasses, I think.”

“She can read some, this one. We’ve not lost the old ways, not all of them,” the mother bragged.

“Ah? Very good. Then I will see you both soon. I must get our little silver friend here back to the lab.”

“Why did they kill them all, father?” the girl asked as the soldiers lifted up the palanquin and readied themselves for the march back to the arcology.

“They were foolish, child, and very scared. For many decades they had learned to think only of themselves, care only for their immediate kind. They turned their backs on knowledge, and then voted in the first in a succession of Destroyers. These men let the corporations take over, and then it was all downhill.”

“Nothing could have been done?”

“Perhaps… if people had given their money to the nonprofits, instead of to the government’s tax collectors. Then, maybe, civil society would have been strong enough to resist the corporations. But they chose not to, and now we will have to spend our lives trying to correct their carelessness.”

“Damn them for not giving their money to the nonprofit organizations, especially ones that concentrated on literature!”

“Yes, child. But together we will rebuild this world, and make sure that people get the message. That way, the nonprofits will be strong in the new society we create.”

“Yes, they must get the message!”

“The message,” the mother repeated.

“Yes, especially when the message is very silly and hidden within what most everyone probably thought was a serious sort of story,” the dix added, staring straight forward and winking, though at whom the doctor could not tell.

“And, also, the new society will come to see life without illusions, will learn to laugh at death, and will know how not to pay attention to trolls. Well, after having smacked them around for a bit,” Maria spoke.

“What’s a troll, sister?” asked the girl.

“We will speak of them in class. You will come? Good. Then, together, we will build a better world.”

The group all gazed about them, seeing the crumbling buildings, the dead hills, hoping, beyond hope, that people would one day get the message… as well as to take a frigging joke without finding the need to leave sanctimonious, passive-aggressive or hateful rot on website comment boards, all while hiding behind the shield of anonymity. (Cough: hintedy-hint-hint.)

*********************************************************************************

Over the past several months, the Minutes Before Six (MB6) team has worked together to incorporate as a recognized 501(c)(3) organization. This means that all donations made to help towards the running of the website – either via our PayPal account by using the button at the top of the sidebar, or our GoFundMe campaign – are now tax-deductible. Please note, donations are only used to subsidize expenses related to the administration of the website, e.g. domain hosting, postage, and providing stationery and other supplies to our incarcerated contributors, and are not used to pay any staff/individuals, etc. Our volunteer team currently cover most of these costs, often without reimbursement, which is not sustainable. We ask you, our committed readership, to consider donating to help defray some of these outgoings; to contribute towards safeguarding the future of MB6. We would also be interested in hearing from you, if you feel like you might want to become part of our volunteer team. To assist us in delivering our quality content week-to-week, we are seeking people to help retype and/or edit entries received from our many contributors. If you would like to become an MB6 volunteer, please email dina@minutesbeforesix.com.

|

| Thomas Whitaker 02179411 Coffield Unit 2661 FM 2054 Tennessee Colony, TX 75884 |

Thomas’s Amazon wish list

Donate to Thomas’s Education Fund

3 Comments

rabbitholedigger

November 1, 2018 at 1:21 pmDon't feed the trolls 😉

Pearls

October 4, 2018 at 1:24 pmMmm that was certainly interesting 🙂

Anonymous

September 14, 2018 at 3:53 amHaha, well done, Thomas!! – Susan