(until I hit you over the head with it)

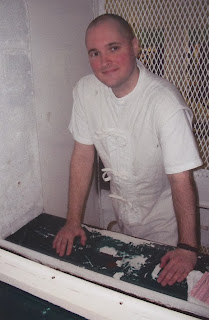

By Thomas Bartlett Whitaker

A panel of hyper-pedantic anal-retentives nearly came to blows this evening on NPR over the thorny and highly relevant subject of typological hermeneutics. Man, if only I had a nickel for every time that mess has come up in my own life, am I right? Just the other day, I was in the dayroom rapping about Starobinski’s take on a poetics of the self when this deranged, facially-tattooed miscreant interrupted me to scream about his set’s preference for Geoffrey Galt Harpham, while waving a shank around in the air. I’m sure you can all relate. Anyways, to be honest, I nearly missed this near-fray, because whenever someone says the words “tropological structure” to me without breaking into laughter, or how such-and-such “problematizes” something else, my mind tends to drift (sorry). I perked back up when one tweedy fellow sneered to another, probably equally-as-tweedy bloke that something he said was “preposterous”. That’s like the PhD equivalent of me telling my psychopathic neighbor that I’d like to do something adventurous and possibly anatomically impossible to his sister. I could audibly hear the other panelists gasp. I half-expected to hear shouting in expository pentameter or perhaps hieratic, technical Greek followed by vigorous, if somewhat feminine, slapping noises. Alas, the moderator was able to rein in these hyperborean passions and, by the end of the show, consensus had been reached on the secular, metonymical structure of self pioneered in Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus. No doubt you are all terribly relieved.

Still, I did get something out of the above. My fearless, intrepid, and never-even-remotely annoying Editor-in-Chief has been on me to write the annual quasi-holiday post, wherein I extol the virtues of MB6, talk about how hard we all work around here, and pretend that a bunch of people who have grown accustomed to gorging themselves at the trough of free content are suddenly going to decide they might like to pay a little for the grub, and where you all pretend for about twelve nanoseconds that you mean to do exactly that this year, before we all revert back to the cynical mean. I confess, I’ve been having, say, motivational deficiencies of late. The above-mentioned belletristic geeks managed to provide me the spark I needed to sit down and grab a pencil. Perhaps not surprisingly, this catalyst recognized itself during a conversation about tilting at windmills.

Not long after the ‘Thomas Carlyle Affair’, the panel discussed the possibilities for the first “modern” novel. The various qualifications for the title were a little obscure (“perhaps we should add that the ‘modern’ is characterized by an epistemological certainty that heralds a sense of true self-knowledge”, which would, if I understand any of that at all, extend the modern to cover at least Augustine). What was most important, was: the novel had to mark the transition from feudalism to capitalism; it needed to focus on the hero living by his own wits; the protagonist needed to be in possession of a Cartesian, subjective reality that most normal people today could identify with; and, that it might parody the aristocratic hero of feudal romance. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra’s Don Quixote was the obvious choice here. This is an interesting choice. Wrong, as it happens, but wrong in a very interesting way, and that’s… you know… great. Or something.

I’m down with Alonso Quixano, Sancho Panza, and Rocinante, don’t get me wrong. It’s just that the Lazarillo de Tormes was written more than fifty years before Cervantes started writing Don Quixote. I say all of this is interesting because the Lazarillo is the story of a cast-out, thief, swindler, prisoner, and general no-goodnik who, via his introduction to the criminal underworld, becomes a cynical, self-seeking, and independent, weapons-grade jerk. He was, in effect, modern literature’s ur-bandit, and he clobbers all of the critics’ bullet points for modernity out of the park. The first novel of the modern age is, ultimately, prison literature.

So was the second, Mateo Aleman’s Guzman de Alfarache; and I like this selection even better than the Lazarillo. Guzman, the protagonist, starts life as a street urchin, beggar, and gambler, before self-promoting into the world of thievery. He ultimately steals his way into a fortune, gets nabbed, and goes to prison. In the first recorded example of the modern “I-got-me-some-Jesus, so-let-me-out” scam, he “repents”, gets a new wife, and starts a glorious and socially upright existence by pimping said Missus out. He gets caught again, and becomes a galley slave, where he is tortured regularly by the Captain. Seeing this, several of his fellow slaves approach him and invite him into a conspiracy to rebel. He manages to snitch on the plotters and, after all of the subsequent summary butchery, he is rewarded with his freedom. Guzman epitomizes the underlying quest of the bourgeois epoch: to escape from rags to riches by outwitting those poor shmucks stupid enough to trust him. Sounds pretty modern, non? (And before you English majors opine, I’m aware that Cervantes also did time in prison. This either proves my point, or highlights that Spain was a damned interesting place during the 16th and 17th Centuries.)

I know you’ve probably never heard of these two books. Don’t blame yourself, because I doubt too many of the impaneled pugilistic professors would have known of them either. The truth is, we are living in an era when stories of incarceration are not seen as important by huge segments of the populace. What I hope to convey to you is that, not long ago, ‘prison lit’ dominated the American market. Once upon a time, picaresque novels about criminals and bandits, crime and confession, were literature. Spoiler Alert: you’ve been culturally programmed not to think too much about our institutions of un-freedom. But you probably already knew that.

Back in the day, the procession from London’s Newgate Prison to the “Triple Tree” gallows at Tyburn was a festive affair. Songs were sung, food was eaten, gin was drunk, and pockets were picked. (So much for deterrence, hey?) Sometimes those to be hanged were reviled, sometimes they were cheered. The purpose of the spectacle was to illustrate the raw, frightening power of the monarch. This was not complex propaganda. People being torn apart by teams of horses, broken on the wheel, burnt on the pyre, or hung until they suffocated is not a difficult semiotic code to crack. “Obey or die” was the message, “and if you don’t like it, you can go to Holland”.

The problem was, dang it, those pesky peasants started sympathizing with the soon-to-be-departed. On occasion they rioted, freeing the condemned and—sorry, I can’t help smiling as I write this—murdering the hangman. In America, the complexities of legal murder proved to be even more complicated, because public executions reminded people of England’s “Bloody Code” and, therefore, of their grievances against the King. Fortunately for colony leaders, Calvinists could always find more Heavenly reasons to hang or burn people, so some of this connection was lost in the religious haze. Still, legal punishments were so haunted by the specter of sympathy that much of the discourse from this era focused on how to make people stop caring about humans based on a state-imposed label.

The rise of the American penitentiary was thought to ultimately solve this conundrum. Benjamin Rush, one of the principle theorists of late 18th Century corrective penalty, wanted to accomplish two things. First, he thought it necessary to move the codes that officials desired to inscribe on the public from the physical site of execution into the realms of the imagination. Even if the populace knew nothing about the interior of a prison, Rush believed they would invent ghost tales and horror stories to describe it: “Children will press upon the evening fire in listening to the tales that will spread from this abode of misery. Superstition will add to its horrors; and romance will find in it ample materials for fiction, which cannot fail of increasing the terror of its punishments”. Very simply, by creating a scale model of Hell and allowing stories from within to escape, the public might be cowed into obedience without the messiness of Tyburn. Secondly, Rush knew he had to pair these stories with a concerted propaganda effort to brand the criminal as a sort of subhuman creature worthy of this new hell. Elam Lynds, a legendary warden of both Auburn and Sing-Sing prisons, called inmates “coarse beings, who have had no education, and who perceive with difficulty ideas, and often even sensations”. “I consider it impossible”, he said, “to govern a large prison without a whip”. The systematic dehumanization of the convict was no secret. It was written into the law, performed in the rituals of prison initiation, and discussed in well-publicized reform debates. Combining these two efforts, Rush believed he could create both an environment meant to terrify citizens into following acceptable norms, and make those citizens trapped within prison into something less than human, requiring no sympathy. Sound familiar?

Rush certainly nailed the first part of that equation. On this side of the pond, early prison literature was entirely confessional in nature. These narratives are pretty tedious to read today, but they were extremely popular amongst the Predestined-and-Happy-about-it crowd. “The Dying Lamentation and Advice of Philip Kennison, who was Executed at Cambridge in New England (for Burglary) on Friday the 15th Day of September, 1738, in the 28th Year of his Age. All written with his own Hand, a few Days before his Death: and published at his earnest Desire, for the good of Survivors” is a good example of this type of story. It also has the dubious honor of possessing the longest title in the history of literature. The purpose here was for the author to offer himself as a negative example for the rest of society to shun; forgiveness was sought, but not in the present world. For forty stanzas, Kennison elaborates on his sorry predicament:

Good People all both great & small,

to whom these Lines shall come,

A warning take by my sad Fall,

and unto God return.

You see me here in Iron Chains,

in Prison now confin’d,

Within twelve Days my Life must end,

my breath I must resign.

A far more insipid example is James Clay’s A Voice from the Prison, Or, Truths for the Multitude and Pearls for the Truthful (1856), which consists of 362-pages of the sort of moralizing that has the curious effect of making one want to go out and immediately commit the very sort of acts of depravity the author was trying to prevent. (At least it had a title you could get through in a single evening.) Confessional tales like this still appear from time to time, including Charles Colson’s tiresome Born Again (1976) and, occasionally, an essay in these pages that I get outvoted on in the editorial penthouse.

Interestingly, this sort of narrative didn’t sell particularly well back in Old Blighty, perhaps because Ye Olde Anglicans managed to mostly rid themselves of the type of Puritan that got off on this sort of rot. Instead, picaresque novels dominated the British market. In these works, the “confession” is given with a wink and a nod, and it was the worst kept secret in the world that everyone read these tales, not for moral edification, but instead for entertainment. Right about the time that the American penitentiary moved from the pages of theory into the real world, American tastes underwent a still-as-yet-unexplained shift away from the confessional mode and towards the picaresque.

My favorite early American example is A Narrative of the Life, Adventures, Travels and Sufferings of Henry Tufts. Talk about a scallywag: this guy was an accomplished thief and con-man, not to mention a notorious womanizer who “made love” to a “damsel” and then ran off to chill with the Indians in Canada to avoid the unfortunate parental responsibilities that soon developed. He didn’t learn any lessons, as he brags often about “successfully prosecut[ing]” his “amour” with a “beautiful savage”. He gets locked up a few times, and manages to encourage readers to avoid “the monster sin” and live a “life of virtue”, all without managing to get hit by lightning: “Should any of the rising generation, by a perusal of my story, learn to avoid these quicksands of vice, on which I have been so often wrecked, I shall feel myself amply compensated for the trouble I have taken in its compilation”. Apparently, this “compensation” doesn’t help as much as he had hoped because, shortly after penning these words, he enlists in the army, passes counterfeit money, goes about as a fake Indian witch doctor, commits more burglaries than I care to count, deflowers more virgins than Henry VIII, maintains several wives, convinces several churches that he is a “saint”, then discovers his true calling as a horse thief. If you are smiling right now, you see the allure of such tales. The man made a mint off of this narrative eventually, showing, apparently, that crime does occasionally pay. By the time Melville published The Confidence-Man in 1857, tales of bad men and their stays in prison were a staple of the literary diet of America. Did you know that? If not, ask yourself: why not? Who, in the drain-swirl of our current political environment, might prefer you not to know this?

Several of America’s prisons proved to be particularly fecund generators of prison literature, none more so than the Manhattan Halls of Justice, a particularly ugly, Egyptian-like pile of granite that became universally known as “the Tombs”. Melville, again, used this prison as the ghost haunting the unfortunate Bartleby. George Wilkes wrote Mysteries of the Tombs, with John Haviland’s prison as its setting, as did John McGinn in Ten Days in the Tombs. None other than Poe lived in the shadow of the Tombs, though I’m not aware of any scholarly work completed on the impact of this edifice on his art – though Poe’s exploration of the theme of incarceration was extensive (think of “The Cask of Amontillado”, “The Pit and the Pendulum”, “The Premature Burial”, and “The Fall of the House of Usher”, to name a few.) Hawthorne, America’s most important author of literature in the 19th Century (so saith I), may have written The Scarlet Letter to look like it took place in our colonial past, but the tactics used to subvert Hester Prynne’s behavior was entirely of a 19th Century flavor. The character Clifford in The House of the Seven Gables has spent many years in prison, and he has obviously been mortified by the experience. Dickinson, alone in her home in Amherst, often wrote about incarceration and solitude. You can’t read Dickens without bumping into a prison somewhere; it’s a major setting in many of his Sketches by Boz (especially in “A Visit to Newgate”), The Pickwick Papers, The Mystery of Sir Edwin Drood, and David Copperfield. He, too, was haunted by the prison: his father was imprisoned in the Marshalsea prison for debt, a set of memories Dickens was never able to shake. This was important stuff in the 19th Century. It mattered to many Americans that this massive experiment in incarceration seemed to be experiencing crisis after crises, and the tales of prisoners were monitored for signs of reform or decay.

Most of you will know the name of Jack London, he of The Call of the Wild and White Fang fame. Did you know he did time? (No? Again, why not? Who sanitized this information from you?) In ““Pinched”: A Prison Experience” and “The Pen: Long Days in a County Penitentiary”, London gives some of the clearest narratives extant about how the prison environment corrupts a man’s best intentions and character. London manages to politic his way into the job of a “hall-man”, who handles direct supervision of a large group of prisoners so the guards don’t have to. The thirteen hall-men peddled all manner of contraband, and London takes great pains to describe a prison economy polluted with “grafts”, “takes”, “pulls”, and sundry other hustles. Most importantly, he shows his transformation from a decent, literary vagabond into a wolf: “It was impossible, considering the nature of the beasts, for us to rule by kindness. We ruled by fear”. “Our rule”, he goes on, “was to hit a man as soon as he opened his mouth — hit him hard, hit him with anything. A broom-handle, end-on, in the face, had a very sobering effect… Never mind the merits of the case — wade in and hit… lay the man out”. “When one is on the hot lava of hell, he cannot pick and choose his path”, he would later say, trying to explain his devolution.

What is remarkable to me is that, not so long ago, stories like these changed public attitudes in favor of reform. I have a hard time wrapping my mind around this; that people actively sought out these narratives and were so impacted by them that they actually did something. You know, other than yawn. Kate Richards O’Hare’s incomparable In Prison, Sometime Federal Prisoner Number 21669 was so well received that O’Hare was ultimately made the assistant director of the California Department of Penology, where she instituted major reforms. Thomas Mott Osborne, a former mayor of Auburn, embarked on a major reform effort in New York based off of the story related in Donald Lowrie’s My Life in Prison. The list of prisoner-written books, essays, and stories that actually altered the real world of prisons during this era is long because, until fairly recently, enough people understood that the state of a nation’s prisons was a sort of gauge of that nation’s moral health. Since most of you read this page while killing the clock at work, look around you. How many of your co-workers would even understand this prison-as-barometer allegory?

During the High Progressive Era (about 100 years ago, more or less), prisons in some New England jurisdictions managed to give prisoners jobs that paid free-world wages, a discipline system that rewarded positive behavior with shortened sentences, meaningful rehabilitation courses, and a drastically, positively improved prison environment. Men were treated as men, and were even honored for their help in powering the United States through World War I, where contract labor from the prisons had a large impact on the war effort. The traditional explanation for what killed this system is that, when the war ended, national industrial output fell and prison administrators lost these same contracts, which, in turn, gutted their budgets. Some of this is undoubtedly true, yet I don’t think this alone explains the sheer rapidity with which prisons shifted tactics during the late 1920s. Around this same time – thanks to a bunch of religious nut-jobs – the nation also passed Prohibition. As a result, crime syndicates sprung out of the shadows to provide the booze that everyone, it turned out, was really rather fond of. Some very public violence broke out in certain places, especially Chicago. Although these instances were statistically fairly rare, they scared people, a fact that newspapers were not slow to notice or capitalize upon. As a result of this fear, legislation was passed all over the nation mirroring New York State’s ‘Baumes law’. These essentially gutted the progressive penology plan by: introducing mandatory minimum sentences; establishing “four-strikes laws” that sent men to prison for the rest of their lives; curtailing or eliminating indeterminate sentencing; reducing rehabilitation options within the prisons; and, forcing wardens to deploy harsh discipline tactics. You can imagine the results.

All of a sudden, machine gun emplacements — unheard of mere years before — were the norm. What had been conceived as a moral project of reform morphed into a more mundane project of prison management. Instead of seeing the goal of prisons as an attempt to make good citizen-workers out of prisoners, the goal became to make good prisoners out of inmates. The prisons rapidly became violent places, and the Baumes laws were quickly booted. But the damage was done. Prisoners felt betrayed. They had obeyed all of the rules, dedicated themselves to winning the worst war in history, and then had been stabbed in the back. Hope behind bars disappeared. Prison administrators soon felt they had no choice but to double down on the repressive policies to manage this discontent. The prisoner narratives from this era testify to a rapid darkening of the carceral environment, but public attitudes were still resonating with the fear of organized crime. Few of these stories, therefore, fell upon fertile ground.

The list of famous writers who spent time behind bars is long: Socrates, Boethius, Villon, Thomas More, Campanella, Walter Raleigh, Donne, Richard Lovelace, Bunyan, Defoe, Voltaire, Diderot, Thoreau, Melville, Leigh Hunt, Oscar Wilde, Agnes Smedley, Maxim Gorky, Genet, O. Henry, Robert Lowell, Bertrand Russell, Brendan Behan, Dostoevsky, Solzhenitsyn, and Jesus of Nazareth. However, if you add up all of the prison lit that made it into print before the 1960s, it would be dwarfed in volume by the sheer explosion of content that came afterwards. Whatever people may now think of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, or Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (if anyone thinks anything about them today), these books, and thousands of others, ignited the fires of a brief but powerful era of penal reform. This phenomenon was very real. What started in the pages of books, infiltrated public consciousness, to the point that it began to change the law.

A number of years before his appointment to the SCOTUS, Harry Blackmun recognized the need to give some genuine substance to the Eighth Amendment: the issue at the heart of most prison lit since the 1920s. In Jackson v. Bishop (1968), he declared that the physical abuse of prisoners met the standard of “cruel and unusual punishment”; a ruling that, sadly, many jurists disagree with today, somehow. Arguing that debates over language represented a pretext for continuing the status quo, he wrote: “We choose to draw no significant distinction between the word ‘cruel’ and the word ‘unusual’ in the Eighth Amendment”, a point that had been made by Iceberg Slim and other prison writers for many years.

Over the next decade or so – powered by the continual propagation of prison narratives that heightened the public’s awareness of abuses that had been normalized since the 1920s – the application of Eighth Amendment protections broadened. In Laaman v. Helgemoe (1977), the Federal District Court for the District of New Hampshire held that the conditions in the state prison at Concord constituted cruel and unusual punishment. This was a pretty far-reaching order, easily the broadest application of the Eighth Amendment; it not only acknowledged the limits it set on the punishment of the physical body, but it also ruled that “its protections extend to the whole person as a human being”. Shocking, I know. In a detailed opinion, the court found that incarceration, in and of itself, could violate the Constitution if it made “degeneration probable and reform unlikely”. This era also managed to temporarily end the death penalty in 1972 with the Furman v. Georgia decision. In Justice William Brennan’s words, the death penalty system was “excessive” and “unnecessary”, as well as “irrational” and “arbitrary”.

Nothing annoys me more about leftists than their continual underestimation of the power of reaction. Several of my progressive friends got really perturbed with me during the Obama years because I regularly fretted over their irrational victory laps every time he managed to do something that pleased them. The time to be most alert, I said, is when you feel most dominant. We never learn. Within the victories heralded by the expansion of the Eighth Amendment, one can find the dissents that would ultimately turn the tide against reform. I encourage the flock of abolitionists that currently loves to flap their wings and crow about the similarities of the pre-Furman landscape to that of today to read Chief Burger’s dissent, for it contains the language that would set the tone for the law of the 21st Century: “Of all our fundamental guarantees, the ban on ‘cruel and unusual punishments’ is one of the most difficult to translate into juridically manageable terms”. The haze that he claimed surrounded this concept would very shortly redefine the limits on torture within the penal context and, in many cases, define these limits away completely.

Just as it was language that prisoners utilized to engender reforms, so too was it language that the judges used to push prison systems into the current mass incarceration era. As courts, nationwide, bowed under the pressure of the Reagan reaction, they sought to create a new framework for prison jurisprudence by giving new meaning to words like “cruelty”, “pain”, “injury”, and even “punishment”.

The first steps in this conservative approach were not small or gradual (something to think about the next time you hear some right-wing AM shock jock moan about “activist judges”). In Rhodes v. Chapman (1981), the majority found no constitutional mandate for “comfortable prisons”, arguing that prison overcrowding complaints didn’t fall within the scope of “serious deprivations of basic human needs”. “To the extent that such conditions are restrictive and even harsh, they are part of the penalty that criminal offenders pay for their offenses against society”. Therefore, short of causing “unnecessary and wanton pain”, deprivations “simply are not punishments”. Not only did Justice Powell fail to specify what degree of severity would actually violate the Eighth Amendment, he also suggested a policy of deference to the penal philosophy of prison officials. In other words, if a warden says something is necessary, who are the courts to argue? Exeunt common sense. Enter madness, stage far-right.

Matters got infinitely worse when Rehnquist became Chief Justice in 1986. Concentrating on the “subjective” expertise of prison administrators, and offering deference to their “special knowledge”, the court raised the threshold beyond which any particular harm could be legally relevant: prison conditions could no longer constitute punishment. (Read that twice, if you don’t mind.) There is obviously just a tad of legal legerdemain at work here. By using an earlier case, Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Resweber (1947), the court started prioritizing the state’s intent over actual facts: it would no longer matter if unnecessary pain was inflicted on an inmate, so long as nobody intended this pain to take place. In Duckworth v. Franzen (1985), the 7th Circuit found that shackled prisoners who were gravely injured when their bus caught fire had no Eighth Amendment protections because this intent requirement had not been met: “Negligence, perhaps; gross negligence… perhaps; but not cruel and unusual”. What happened was, effectively, no different from “…if the guard accidentally stepped on the prisoner’s toe and broke it”.

Whether the context is a prison riot, shoddy medical care, or confinement conditions, the law’s preoccupation is with the knowledge, deliberation, or intent of those in control. If not a specific part of a prisoner’s sentence, deprivations are not punishments unless they are imposed by officers with a “sufficiently capable state of mind”; a standard that is almost never reached in the real world. If you understood none of the above, here’s the point: no matter how much actual suffering is experienced by any of us in white, it cannot be deemed unconstitutional unless the intent requirement is met. When Scalia dismantled the “totality of circumstances” test established in Laaman, which condemned the “cold storage of human beings”, he used language reminiscent of 19th Century slave law to establish the precedent that no action by prison administrators is unconstitutional so long as it serves a “legitimate corrective purpose”. What is a “legitimate corrective purpose”? Anything they want it to be. What happens if these purposes are so inhumane that they cannot fail to produce monsters of inmates? Nothing, nothing at all. Prisoners’ crimes no longer explain their treatment in any rational way. Instead, as conditions convert men into desperate animals, society has begun inventing a new kind of criminal. Born in prison, this new class of so-called “super-predators” has given politicians all the reasons they need to request funding for yet more prisons, more solitary confinement buildings, and longer sentences. Whatever these hand-wringing politicians may say when the cameras are out and about, many of the men around me were created by a legal fiction. Take a look at the sorts of cause-and-effect relationships you think define law and order, and then reverse them.

This legal landscape allowed administrators to impose new controls over the receipt and transmission of prison-themed literature. For the first time since the birth of the penitentiary, both halves of Rush’s goals were met, and what market existed for tales from the carceral abode was tiny and underfunded. Jack Henry Abbott had his brief moment in the sun, until he fell in true Icarian-style — taking the rest of the industry with him. Thirty years into the mass incarceration era, we are at a point where the public has almost zero sympathy for the prisoner because they know almost nothing true about them. We are still waiting for our Dostoevsky, our Wilde, our Victor Serge to rise from this quagmire.

I won’t pretend that you will find this figure here in these pages — though I won’t discount the possibility, either. Since prison administrators learned hard lessons from the prisoner rights movement of the 1960s, they are very aware of how to prevent radical ideas and literature from infecting (read: educating) those trapped behind these walls. Most of us have had to teach ourselves how to write, and it shows. I know I cringe on those rare occasions when I read something I penned years ago. Still, for all that, mb6 is filling a gap that was once packed with consumer magazines willing and eager for stories from the depths. Since prisons have proven, time and again, that they cannot be trusted to provide meaningful, humane oversight of their operations, we, too, must fill in that gap. I have traveled often over all the old grounds as to why I think we are worthy of your eyeballs, your comments, your spare nickels. Only recently have I come to think that perhaps our most important function is to act as one brick in the wall of the humanities that stands between the human heart and the creeping shadow of brutalization that seems to be encroaching over the West. Just look at the news: we regularly accept behavior out of our politicians, our religious leaders, our cultural stars that would have been unthinkable in the recent past. We have almost completely lost our understanding of the definition and importance of ‘shame’. When Joseph Welch asked McCarthy, “Have you no decency, sir?” people understood this to be a meaningful attack: one that stung, one that shamed. Try saying those words to yourself the next time you watch Our Dear Leader on the television, or, better yet, say them out loud to the jackass in the queue at Jamba Juice who seems to be laboring under the twin delusions that smart phones only work when you raise your voice to them, and that a sentence isn’t complete unless it’s liberally sprinkled with f-bombs. Clearly, shame is not something most of my peers — or our warders — have a firm grasp of. I sometimes wonder if I’ve grown soft in my middle aged-ness, because brutish, tasteless actions now wound me in a way that is hard for me to describe. Maybe I’m too sensitive, but at least I’m not numb; that seems to be the best adjective I can think of for our anesthetized, dazed, stunned, and insensible postmodern predicament.

How do you learn to feel again? You open yourself up to others, take them into your arms, just as you would if you’d spent all day out in the snow. You do this even though it means you are allowing the Other to get close enough to wound you – vulnerability is the point. I’m convinced that literature is one way to manage this. When you step into someone else’s words, you are wrapping your mind around their subjective understanding of the world — the practical definition of empathy. This allows you to experience events, people, places, and emotional states that are totally foreign to you, and to learn to think about things from multiple viewpoints. In a nation increasingly separated by religious, political, and factual divisions, it’s the easiest way to knock fences down.

If this means anything to you, please consider supporting our work this year. We are currently wading our way through the 501(c)(3) application process and, if we are successful, your donations will become tax deductible. If monetary aid isn’t feasible right now, consider volunteering: we are maybe only one or two volunteers from being able to move to a bi-weekly posting schedule, meaning more stories, more essays, and more takes, both good and bad. Consider posting a link to your social media accounts the next time you read an article that touches you, and then talk to the people in your life about why this is. If, for no other reason – but because I like to think that after more than a decade at this, my time hasn’t been completely misspent – do this for me. My execution date has now been set. So, this is likely my last attempt to beg you for some goodwill (halle-freaking-lujah!); I’d really like to see MB6 on firmer footing before I kiss the Yeehah Gulag goodbye. Knowing that this means something to you would, in turn, mean a great deal to me. Charon once charged an obolus for a trip across the Styx. I’m giving you the ride for far less. What say you? Are you with us?

There is a tide in the affairs of men, a nick of time. We perceive it now before us. To hesitate is to consent to our own slavery.

– Brutus, Julius Caesar

|

| Thomas Whitaker 999522 Polunsky Unit 3872 FM 350 South Livingston TX 77351 |

Thomas’s execution is scheduled or February 22, 2018

The rest of your Minutes Before Six Admin Team:

|

| Susan |

|

| Teri |

|

| Lorna |

|

| Dorothy |

|

| Steve |

|

| Dina |

To make a donation to support Minutes Before Six, click here

or ![]()

A large number of prisoners that contribute to Minutes Before Six are without

family or outside support. If you would like to “adopt” one for the holiday season,

please email me at dina@minutesbeforesix

Thank you!

23 Comments

piscator

June 3, 2018 at 9:50 pmMr. Whitaker,

Your exposition certainly ranks among the finest literary efforts I've encountered! More than that, I am deeply, deeply touched. I'm very familiar with the authors you cite and, frankly, I think they would be equally moved by your writing.

I will write on your behalf and make a donation.

My sincere thanks, Piscator

piscator

February 22, 2018 at 3:51 amIt would be tedious for me to relate how I found this website doing research on 'attributional studies in the Shakespeare canon' — but it does seem ironic! 🙂

Mr. Whittaker, your exposition ranks among the finest literary efforts I've encountered! More than that, I am very deeply touched. Also, I'm familiar with the authors you cite, and, frankly, I think they would be equally touched by your art!

I'll will certainly write on your behalf and make a donation.

Sincerely, Piscator

Anonymous

January 17, 2018 at 2:38 amThomas, I have made a donation to support this page and to help spread the word against the death penalty. Your story brought me to this website a few years back and your words and work here have moved me more than you know. Thank you for everything.

Anonymous

December 8, 2017 at 1:08 amIs thomas planning on writing any more of his series "No mercy for Dogs"…? I check all the time…I know he must be going through unthinkable emotions right now. I hope he knows people care about him, appreciate his voice, are thinking of, and are Praying for him.

-S

A Friend

December 1, 2017 at 2:54 amIf your comment is published, it gets printed and mailed to the MB6 writer. If you want to be sure Thomas reads your thoughts, you can write to him directly at the address under his photo or through http://www.jpay.com. It's not necessary to rely on leaving a comment here.

Anonymous

December 1, 2017 at 1:53 amI have debated for a long time about leaving a comment here, but after hearing that Thomas's execution has been given a date, I decided I wanted to share some thoughts with the hope that he will indeed get to see them. My question to MB6 is, if I post here, will he be forwarded the message?

Thanks so much

Anonymous

November 29, 2017 at 2:56 amThomas, I am just a regular Joe Schmo, and so I had to google some of the references in your post. It is what it is.

I have followed this blog for quite a few years. I believe the death penalty is cruel and barbaric. My words seem to be truly inadequate, and I can not comprehend how some prison employee could bring you into their office, and detail the date, and the exact time, when they are going to kill you. I guess the insanity is compounded by the fact that this only takes place in some parts of the country. It is all so senseless and arbitrary.

I have no answers. The death penalty is an abomination, and it demeans and soils all of us who live here in the USA. May Heavenly Father be with you at this time.

Anonymous

November 28, 2017 at 8:55 pmDan, while your rejected bloodlust is commendable, other aspects of your message are problematic.

First, I find your erroneous noun-verb correlation, in a post intended to ridicule those of us who bother to critically review available information (as responsible and moral human beings should), even more "adorable." "Responses" aren't capable of the act of writing, as you seem to believe they are.

Furthermore, we "adorable" commentators of course do not condone Thomas's crimes. Nor, however, do we take the cursory, unqualified diagnoses of unethical prosecutors or the sensationalist sound bites of slipshod reporters at face value. That's why I, for example, have bothered to read and analyze all of Thomas's writings (which span a decade). These are absolutely saturated with his regret and remorse. He in NO way possesses "extreme and total lack of empathy or care." Anyone with basic reading comprehension skills should realize this.

I question how someone who claims to prize intellectual aptitude and independence can't engage in accurate literary and psychological analysis. I suggest you either read or reread his entries before continuing to disseminate such ignorant assumptions. Four diagnoses from four different psychologists/psychiatrists are also available online if you consult his appellate records – all publicly accessible for those who bother to do actual research.

I sadly don't question, however, how someone with such a black-and-white worldview who feels so compelled to condemn others can't understand how precious truth and independent thought are.

Dan

November 28, 2017 at 5:33 pmI find it adorable that there are so many responses to Whitaker who can actually write very well. Seems that extremely bright people do visit this site to read his writings.

As for Thomas, while I can not condone what you have done to your family, the heinousness involved and the extreme and total lack of empathy or care for them, I do hope you will get a stay of execution.

I question how someone as bright as you can't understand how precious life is.

Anonymous

November 27, 2017 at 2:21 pmThomas,

As someone who writes you frequently, I have been overcome with a lot of emotions on your pending date. As always, your writing and ability to tell a great story continue to impress and enlighten. I applaud you for continuing to give a voice to those who have none and for your willingness to fight for the little guy. I wish you nothing but the best and am truly hopeful that something will change before February. Try to keep your head up, I realize it's not easy right now.

Until next time, I wish you well. -Ken

Anonymous

November 26, 2017 at 5:07 pmDear Thomas

Thank you for showing the connections. It also shows, that the people in this world still have a long way to go. Because it has not become more human, it's just trimmed to handsome.

I learned so much from you and from others in D/R, things I can not even think, how people treat other people. And I also learned – that one as a "number" – can to fight for justice and right! You have set in motion a lot, what many people outside did not made. And if I put the perspective on you, as a human, then I can see what you have done! In the good sense – for humanity. Human dignity is inviolable ~ that is a foreign word in America especially in the prison system! Because no matter what a person does, the right to dignified treatment remains.

That's the way it is with us and that's how it is done – and it works…

And so remains for me simply say – may you experience humanity and decency in the place where you are now… and may peace be with you and your family… The last word is not spoken yet, because in America is sure, that nothing is sure…

And so I send you my best thoughts and my compassion. From Human to Human…

HeavenWanderer, Switzerland, You know 😉 Big Hug …

I am sure that the day will come: One day we will end this death penalty! And yes I will keep helping to fight for justice and humanity. Peace!

When we practice Loving Kindness & Compassion, we are the first ones to profit. ~Rumi

If all people understand that ~ then peace can be on earth and among the people.

Anonymous

November 26, 2017 at 3:08 pm"Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him."

A wonderful quotation.

I like this one from C.S. Lewis: “So loving my enemies does not apparently mean thinking them nice either. That is an enormous relief.”

Two wrongs don't make a right. Capital punishment is wrong. I can understand a policeman having to kill a maniac wielding a samurai sword, but somebody who has been captured and incarcerated is not a threat to society. There's something very cold, clinical and wicked, about the state murdering a man in such a fashion.

A few more fitting quotes:

“What can you ever really know of other people’s souls—of their temptations, their opportunities, their struggles? One soul in the whole creation you do know: and it is the only one whose fate is placed in your hands. If there is a God, you are, in a sense, alone with Him.” – another from C.S. Lewis

“As one reads history, not in the expurgated editions written for schoolboys and passmen, but in the original authorities of each time, one is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed, but by the punishments that the good have inflicted; and a community is infinitely more brutalized by the habitual employment of punishment than it is by the occasional occurrence of crime.” – Oscar Wilde

'for fall have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.' – Romans 3:23

I will pray for you.

GM, Glasgow, Scotland

Jenneke

November 25, 2017 at 6:38 pmDear Thomas, family and friends,

I'm very sorry to learn of Thomas'his execution date. I believe that Texas, once again, is carrying out a grave injustice both against Thomas and also his family who will once again lose one of their own. Even when his family told the authorities that they do not want him executed, Texas only cares about their revenge..

There's is nothing anyone can say that can make this remotely better but I hope with all my heart that his sentence will be commuted.

Should the worst happen I'd like to thank Thomas for all his writings here on MB6 and for all that he taught us. I believe his case shows that we can all become better than what we were before and what we can achieve if we start reforming people instead of just warehousing them in prisons. My heart is hurting over what is about to transpire for him and his family. I wish you all strenght in the days to come..

Love, J.

A Friend

November 25, 2017 at 6:13 pmChubarrow, the line originally read, "My execution date will soon be set…" but was edited for publication with Thomas's permission.

Chubarrow

November 25, 2017 at 6:11 pmFor avoidance of doubt see the last paragraph:

"My execution date has now been set. So, this is likely my last attempt to beg you for some goodwill (halle-freaking-lujah!)"

A Friend

November 25, 2017 at 3:09 pmThomas's post was written before he knew about his execution date. It was held by his mailroom for a month for unknown reasons. And yes, it takes time to prepare essays for publication, so there is always a delay between the time one is written and the time you are reading it.

I published the first comment because I believe the commenter intended it as helpful. This doesn't mean I agree with it, just that I understand the sentiment he wishes to convey to Thomas.

There are several hateful comments I haven't published. If only you could see those, you would understand the difference between constructive and disturbed.

My thanks to those who have commented and donated so far. Wishing you all peace this holiday season – Dina

rabbitholedigger

November 25, 2017 at 5:09 amMaybe this was written before his execution was scheduled .. I assume there's a bit of a delay in getting his mail out … anyway whatever the case there's no point telling him what to think or feel. He's obviously thoughtful enough to decide on his own. It's also possible that he doesn't feel the need to bare every bit of his soul in his blog. It's not imperative that you make a parade out of your relationship with Christ.

Anyway as for the 'homily' – MB6 has been great, and I hope it carries on if worst comes to worst and Texas pointlessly takes Thomas away from us.

Anonymous

November 24, 2017 at 11:43 pmThomas, your observations on American penology are an excellent synthesis of Foucault and your own conclusions and experiences. Your writings are unsurpassed in their critical focus from the vantage point of personal experience. What is so strange about American society is the confluence of liberalism and barbarism, and you explain very well that the semiotics of the prison-sign complex have been removed form the public gaze as the prison system has reverted back to primitive infliction of suffering. I always look forward to your articles.

Alex G.

Emily M.

November 24, 2017 at 9:21 pm[part 2]

2) Why do I say you haven't truly read and comprehended Thomas's past writings, even though you state his "puerile tone" is "typical of his writing style?" Because anyone who's actually done so realizes that his tone is a defense mechanism, a wall he throws up to brace himself against the rejection and condemnation that spews forth from so-called God-fearing Christians. Want proof?

Thomas himself explicitly addresses his tone. He analyzes his own faults and motivations far more than most people do. Read, specifically, his entry called "A Wilderness of Mirrors" from 4-25-11. In it, he writes:

"Look at me, look how post-modern I am, how smug, how comfortable in my blanket of ennui, my grimness. Now please, pat me on the head, tell me things are going to be ok, that the twisted acid polluted wreck of my world is not truly fatal, that I am not really just a ghost floating over my mangled body being looked at by EMTs. Please. Anybody. Redeem me. Please. I want to describe the walls that I put up between myself and other people because in my heart I am terrified of anyone seeing who I am, how stupid, how ignoble, how utterly petty I can be.”

If someone reads this and still believes Thomas doesn't care about his death and doesn't realize that his tone is a desperate attempt to protect himself, I can't help them. I really can't. That kind of blindness points to a bitterness, a simplistic worldview, and a lack of empathy I can't even begin to address. And sadly, that applies to a lot of the commenters on this site.

3) So if you've bothered to read my preceding arguments, you'll also realize why I'm disgusted by your shallow posturing here: "you will meet your father's God in less than 90 days. I sincerely beg you to make the most of the short time you have left to you. Please worry less about your blog postings and more about the condition of your heart."

Again, if you'd bothered to truly analyze any of his previous entries and consider their trajectory as a whole, you would see that clearly these writings ARE his attempts to wrestle with the condition of his heart. Any writer knows this. If you don't believe in the therapeutic qualities of writing, you've obviously never read any literature worth its salt. I offer, to start, all of Dostoevsky's novels and every single Holocaust narrative ever written.

Oh, and God is everyone's God, whether we know He's there or not. Again, Jesus and Paul addressed this when they confirmed everyone – the Gentiles, the non-believers, everyone – was entitled to salvation and love. So I fail to see why you're singling out "his father's God." A leftover strain from Puritanism perhaps, they of ill-conceived predestination and the Salem Witch Trials?

4) Your empty promises about "thoughts and prayers" are just self-serving, ego-stroking bleats if you don't bother to actually read Thomas's posts and understand him. God WANTS us to understand and empathize with each other. He WANTS us to do this hard work and not just scramble up on soapboxes and flounder through the motions like Pharisees. My proof? Jesus's commandment to "Love your neighbor as yourself." To love someone means to bother taking the time to understand them, especially when they've written 152 entries over the course of a decade. All you have to do is actually read them.

5) Lastly, how horrifically callous and belittling to admonish someone on Death Row to "make the most of the short time left to you." One, obviously, he is – as anyone who reads my comment and more importantly Thomas's writings will realize. And (2) have you ever been on Death Row? Have you ever known the exact day and time you will die? How the heck are YOU qualified to lecture someone living in a hell you or I could never truly understand?

Emily M.

November 24, 2017 at 9:21 pmAnonymous, your post is so callous and hypocritical and demonstrates such a (to use your gold-star SAT term) "puerile" black-and-white worldview, I hardly know where to begin. But as a Christian myself, and in the name of actual compassion and critical thinking, I'll do my best to respond.

I challenge whoever's skimming this to read this entire comment, even though it will be a long one. And please respond, if you're going to do so intelligently and thoughtfully. I welcome disagreement and discussion as long as it's not hysterical and "puerile."

I'll ask you to keep in mind this quotation from Fyodor Dostoevsky, one of the most staunchly Christian writers of all time (as evidenced by Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov, both of which grapple with difficult questions of redemption and mercy):

"Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him."

You, like so many others, clearly are more inclined to denounce someone. Yours is an Old-Testament view of faith. Any true Christian knows that Jesus Christ came to show mercy and compassion. He disapproved of evil acts, of course, but He didn't just throw someone to the hellfires or attack their humanity. He treated them with kindness, with understanding. Don't believe me? Reread the story of the townspeople trying to stone the adulterous woman.

1) Your dismissal of Thomas's writing style as "puerile" and "inappropriate" proves you have (1) failed to consider the function that tone plays in enhancing content and subtext (a basic tenet of literature), (2) not comprehensively analyzed Thomas's past entries, and (3) thus not bothered to use available resources to understand his psychology.

Before you pass judgment on a man's soul, you owe him that.

In this country, we have the means to research issues for ourselves and go beyond what self-serving prosecutors and bloodthirsty media zombies crow at us. If we don't do so, we're being lazy and cannot possibly offer informed, perceptive opinions on a subject. If I were a teacher and a student came to class who obviously either hadn't done the reading or just skimmed either the text or the SparkNotes, I'd tell him he was ill-prepared. I'd tell him before throwing in his two cents, he needed to actually read and THINK about the assignment.

urban ranger

November 24, 2017 at 9:20 pmDear Thomas

Please know that there are so very many people who care about you.

Your writings have been sometimes amusing, often heartbreaking, and always instructive. Thank you.

Like many others, I will be sending positive energy your way and hoping that your situation changes between now and February.

Stay strong, Thomas. Bless you.

Anonymous

November 24, 2017 at 9:20 pmThanks for this Thomas – educational as always. I wonder if 'monsters' like yourself got dehumanised partly in response to Silence of the Lambs. How many people thought that all DR inmates were Hannibal Lecters? I know there is more to it than that but the word 'sociopath' is thrown about so easily and Lecter is one of the most powerful portrayals that we have of that in pop culture. That's why executions have to be carried out in secret now (with hospital apparatus as if it was a medical procedure) as the public hangings of the past tended to make us empathize with the soon to be deceased.

As for the self-righteous post above, I think the condition of the hearts the executioner and his assistants is more to the point – but as usual, the religious nutjobs don't get it. Anyway, rest assured that your words have made a difference. You exposed the Yeehah Gulag for what it is in an extremely vivid and poignant way and your words will live on.

Thinking of you at this difficult time – hopefully lots of people will write to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles asking for your sentence to be commuted to life.

Anonymous

November 24, 2017 at 6:40 pmMr. Whitaker, my thoughts and prayers are with you. Your puerile tone, while typical of your writing style, is particularly inappropriate at the present time. Since the date of your execution has been set, you will meet your father's God in less than ninety days. I sincerely beg you to make the most of the short time left to you. Please worry less about your blog postings and more about the condition of your heart. I wish you nothing but the best and will be praying for you until the very end.