It was 1986, earliest January. I know because the poofy coat I got for Christmas was still poofy and the cheapest variety of poofy coat only held its poof for a couple of weeks. After that it became a sweater with buttons and zippers. This one was blue. It had too many pockets. It didn’t have a hood.

The day, of course, was Monday: the funeral service for the weekend. I hated the school bus. Screams banged against the tall green cushion at my back. The crowns of those who knelt in the seat in front of me seemed always in danger of looking back, noticing another in their midst. Miscellaneous items flew by overhead, most aimed for the bus driver. It was chaos. I sat my most invisible still, backpack in my lap, secretly picking at a loose string from one of my poorly crafted poofy coat pockets. Sound and movement warred all around me. I was a pebble at the bottom of a raging river. I wished my coat had a hood.

School bus brakes whistle-squealed me to a stop. School bus door squeak-banged open. Blackwell Elementary School was a two-story, capital T-shaped build, left stranded in the middle of the Blackwell Housing Projects. That was a different kind of hood. The school and the projects were made with the same materials: red bricks, black asphalt, broken concrete and brown faces.

Small people poured through the narrow bus door, across the spider’s web of broken sidewalk, to splash their filthy hands onto the rust-red entrance doors. Inside a side stairwell led those lucky enough to arrive early down to the lunchroom where breakfast would have been served. For those of us who always arrived too late for free breakfast there was only the wide stairwell that led up to the school’s main floor.

To the left at the top of those stairs was the auditorium where I was the first one kicked off the stage in the school Spelling Bee for misspelling the word “very.” Every class was required to send an offering. It was the law. The word was simple, so the laughter was justified.

To the right at the top of those stairs was the administration’s office where I was told to wait outside, on the curb, until my Grandma came to collect me, the last time I showed up to school wearing clothes I had slept in and wet the bed in. That was one more instance that proved kids and adults say the same things to a child who shows up to school smelling like the furthest stall at the back of the bus station bathroom. I faked the call to my Grandma. No one was coming to pick me up. No one noticed when I walked away.

I was drug between these two memories every morning that I was dumb enough to show up for school. And on, forward, into THELONGESTHALLWAYONEARTH. It stretched the length of the base of the capital T of Blackwell School. And on the days that I showed up I was swept along and down into it on wave after wave of five elementary school grades worth of strangers. A jostling flow of shrieking and giggling. As a duly appointed official stinky kid, I was required to stare at the floor as I shuffled my way forward. It was the law.

On my periphery I saw their excitement at finding each other again, as if a weekend was a summer vacation. In pairs and in groups they separated from the greater shambling herd to enter their classrooms together. While I, of huge head and pencil neck and narrow shoulder, walked on pretending not to hear the stray, urine-related comments. My lips never parted to reveal the space where my tooth was missing from when Melvin curb-stomped me two years prior. My eyes remained low atop the dark smudges that I had inherited from my mother. I obeyed the speed limit and moved forward and down.

Classroom doors, having ingested their fill of students and teacher, closed. Side stairwells stole away those whose classrooms were on the second floor. I held onto my nearly empty backpack’s shoulder straps raising my head more as the hallway emptied, more and more as there were fewer people, less noise and fewer around me.

At the end of THELONGESTHALLWAYONEARTH I turned right into the top of the capital T. My classroom sat in a dim corner, last door on the right. A staircase sat directly in front of the door so as not to offend the classroom across the hall. It was common knowledge that you would be cursed with bad luck if you walked past my classroom while the door was open. It was next to the exit door. It was the retarded class.

It said Learning Disability (L.D.) on my report cards. I always said retarded class because that’s what everyone else said. Tucked into the furthest corner of the school, under dying florescent lights, hidden behind a staircase, the door was left sitting beside the exit like trash bags for the dumpster.

The inside of the room was a whole other matter. Whitish vinyl hallway tile turned into cleanish orange industrial carpet at my classroom’s threshold. A low, crescent moon shaped table sat to my right when I entered. It had a blue plastic chair behind it. A coat closet that students never used sat crammed with miscellaneous teaching implements in the corner on the same wall. The teacher’s desk sat in profile in front of the coat closet. Tall, ashy green chalkboards were on two walls. Tall, dust clouded windows were on the other walls.

I was small for my age, so the room seemed big, and it was twice as long as it was wide. The desks were spread out far enough that on most days I could quiet fart and no one would know. There were more students, but I only remember three others.

Dominique was the tallest person in the class, but he slouched to hide it. He had buckteeth, curly hair and always gave off an impression of impending flight. He was in my class the year before, too. He and I were both 5th graders.

Mario’s desk was between Dominique’s and mine. He was in 3rd grade. Light skinned, small with a beak for a nose. Annoying as hell. Everything he said was a baby’s invitation to play.

Because there were so few morons in the school my class was for 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders. 1st and 2nd graders were in the room next door. Some days it sounded like a civil war reenactment over there.

I could not stand Malcolm. His desk was on the end between Dominique’s desk and the far wall. He was in the 4th grade. He was always coming to school with some new clothes and shoes that I couldn’t afford. His face looked like a whole wheat muffin with the top pulled off. A flat-nose, spotted-faced troll had to keep tell everybody what his new Adidas cost. Ain’t nobody even ask.

My teacher’s name was Ms. Brown. Lord smite me now, she was so fine! Dark skin the color of a calm, stout beer. All feminine angles and graceful movement. She smelled like vanilla. She floated over my world raining down acceptance and patience and understanding. The light from her almond-shaped eyes warmed my inner student. She had the same country ass and Virginia accent as everyone else but, in my memory, it is music.

We students were all under her magic spell. No one ever talked back to Ms. Brown. We never threw things when she turned her back. I never caught an attitude because a math problem kept adding itself incorrectly under my pencil’s lead.

We lived for her every word and drank in her frequent smiles. To this day I have never seen another woman whose collarbones do for her what a diamond necklace does for other, lesser humans.

One reason for my personal connection to Ms. Brown was her teaching method. We were not all stupid in the same direction. Therefore, we received individual personalized lessons. Ms. Brown would call us one, sometimes two, at a time to the crescent moon table, where she would walk us through the day’s lesson on any given subject. When one of us got up from that crescent moon table every other face in the room would be pointed at Ms. Brown hoping to be the next one summoned into her presence.

The best grades I ever got were in her class. Ms. Brown made the bus ride and long walk to class worth enduring. Ms. Brown made that classroom a sanctuary.

On this particular Monday morning two things jumped out at me as soon as I entered the classroom. One was that someone had stood an old, dilapidated loveseat on its end and left it over by Ms. Brown’s desk. The other was that all of Ms. Brown’s things were missing from on top of her desk. She had a collection of knickknacks given to her by me . . . and some other students too, or whatever.

My desk was on the end, closest to Ms. Brown’s and the crescent moon table. I put my still mostly poofy coat on the back of my chair, sat down and took out my notebook and pencils ready for the day.

“Good morning, children,” the loveseat sang, too loud. It waddled to the chalkboard at the front of the room. “My name is Ms. Crenshaw,” it said, while writing its name on the chalkboard in too-big letters. Then the loveseat turned to the class and said the two most depressing sentences of my academic career.

“Your former teacher Ms. Brown won’t be coming back. I will be your teacher from now on.”

“What the fuck did you just say?” I yelled at the top of my voice, out loud, inside my head.

New teacher?! Couldn’t be true. This bitch lying. Smiling the whole time she lying. Walk up in my classroom, writing her jagged ass name on the chalkboard like she really serious. Crenshaw. Shit sound like the noise a car make skidding sideways on its way off a cliff.

Shapeless heifer came in here in some sewed up, discount, funeral home curtains. Oily forehead, dry haired, sour faced. How was I supposed to replace a calm stout beer with septic tank drippings?

Ms. Brown not coming back. Those words did not fit together. There was no way.

Mercifully Crenshaw gave us all work to do on our own, at our desks. We were all quiet in our grief and shock. Crenshaw appeared at my desk with a grey mug in her hand. When she held it out to me, I saw it had a big, ugly ass blue star on its side. She told me to go fill it with water from the fountain at the top of the stairs.

When I got outside the door I carried her Dallas Cowboys mug with the cuffs of my long sleeve shirt.

Of all the bullshit that Monday had thrown at me during my short, uneventful life this was top 3 worst ever. And first thing in the goddamn morning, too.

Fuck you, Monday! Go Redskins!!!

“Ms. Brown dead,” Mario sang in a half whisper.

“Yo momma dead,” I shot back in a near whisper. I was not trying to hear any of that shit. Especially from a baby like him.

“I bet she got runned over by the trash truck.” His ass had the nerve to laugh when he said it. I ain’t sat down a whole minute after fetching Crenshaw’s water and gotta hear this shit. Why was his desk beside mine?

“You want Ms. Brown to be gone,” I said, “’cause Crenshaw your girlfriend.”

Mario’s face scrunched up until it looked like a fist with a nose sticking out of it. “Uh-uh,” he said, ” she smell like my grandaddy closet.” He stuck out his tongue like he tasted poison before adding, “Crenshaw probly the one kill Ms. Brown.”

“She ain’t dead,” I hissed in frustration. I leaned toward Mario so Crenshaw wouldn’t hear me at Ms. Brown’s desk. ” Crenshaw don’t know shit. Ms. Brown be back. Watch what I tell you.”

“Bet she don’t come back.”, he said. He offered up his booger-hooking ass pinky, right in my face, daring me to take his bet. “Bet a million dollars she don’t never ever come back,” he said.

“Bet,” I said. I bent my pinky with his to lock in our bet. “And you better have my money when I win too.”

Behind me Crenshaw was constantly clearing her slimy-ass throat. She kept shuffling papers around for nothing, opening and closing Ms. Brown’s desk drawers. She was doing too much at that desk. It wasn’t her desk. I should have called the police on her for the crime of desk trespassing. Deskpassing Bitch!

There was always a grunt when she stood up. I watched over my shoulder as she waddled over to the crescent moon table.

Abomination!!!

For nearly two years Ms. Brown and only Ms. Brown sat on that inside of the crescent moon table. It divided her so the view from my desk was all beautiful face, soft, slim shoulders and slender arms framed against a background of dusty green chalkboard, further emphasizing her delicate silhouette, from lustrous hair and unblemished forehead to upper midsection. While under the table the tops of her calves ran like chocolate waterfalls in shadow down to crossed ankles on small feet in high heels.

How far the crescent moon table had fallen to now having someone’s escaped pet bison grappling with the chair that Ms. Brown had so blessed with her presence. Not even bothering to lift, just dragging the blue chair over the carpet with her cloven hoof, just to dump so much unnecessary girth into its seat. She scooted the chair closer to the table with a heaving shift, throwing her bulk forward until her stomach was bisected by the tables edge. Poor crescent moon table probably wanted to throw up. She leaned forward as she opened Ms. Brown’s lesson plan. Shapeless titties poured onto the fake woodgrain surface with only whatever potato sack Crenshaw had happened to wrap around herself for separation.

Don’t worry little crescent moon table. It won’t be long before our teacher comes back. Bad things don’t happen to kids.

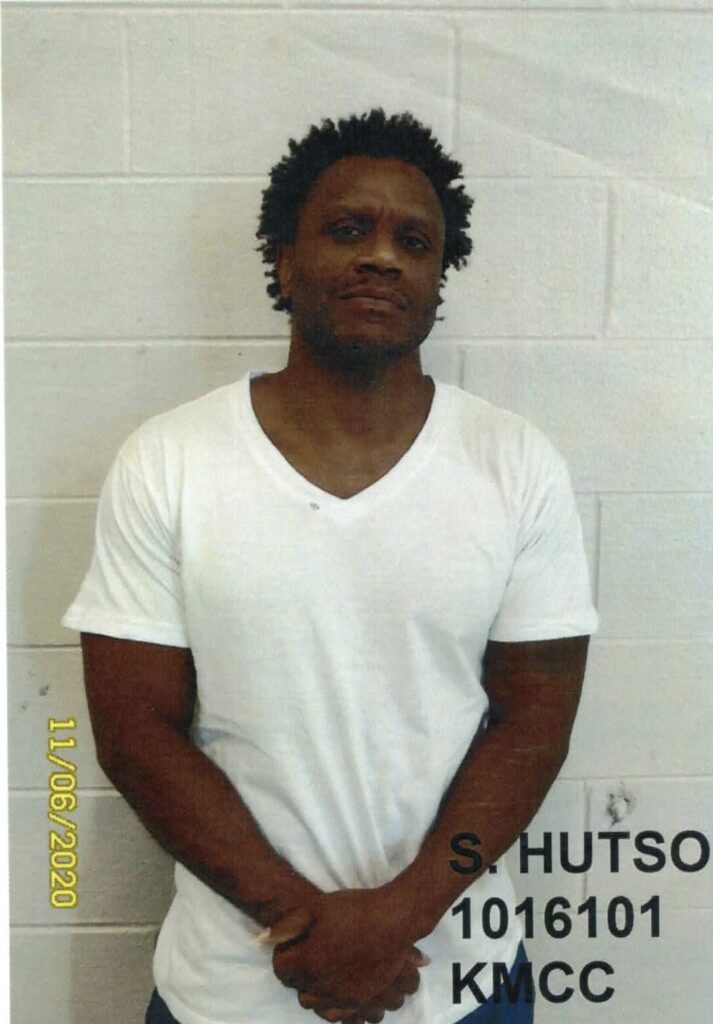

Crenshaw looked up and fastened her piggy eyes onto me. I looked away hoping that she would pass me by. “Shedrick,” she said.

“Present.” I tried.

“Come here,” she demanded. I rose slowly and shuffled over to the table. I knew I was supposed to sit down but I was holding onto the hope that she might give me work to do at my desk.

“Sit down,” she commanded. Then, “Where is your homework?”

I said, “I forgot about it,” which was true, and ” We ain’t never have homework before you came,” which was also true.

Crenshaw leaned back to her full sitting height. She grew tall in Ms. Brown’s blue chair. Her silhouette contested the chalkboard for the title of dustiest. She looked down her bulbous nose at me. A smell like old shoes still not dry from yesterday’s rain reached me across the table. “I don’t care what your last teacher did. I’m here now.” Crenshaw waggled her mason jar head side-to-side as she warmed to her lecturing. “I expect you to put forth your best effort whenever I give you an assignment. Do you understand?” Her voice was a trumpet blown by a beginner’s lips. All pitch and no tune. Just a bunch of flat notes strung on a line, cracked like a whip.

“Do you understand?” she repeated.

I mumbled. I understood. My head had bowed. My eyes had fallen to the table. They stayed there as Crenshaw drug me down through a lesson that I paid less than no attention to.

After an unmercifully long few minutes of nodding my head when it seemed appropriate, I was finally released back to my desk.

As I turned to go, I noticed that everyone else’s eyes were down.

The smells of food filled the school. Low-income households meant free breakfast for those lucky enough to arrive at school in time for it, and free lunch for everyone. We all guessed at what was on the menu while peeking, peeking, peeking at the clock high up on the wall.

On command we formed a line. We went down the hall to the stairs, down to the basement cafeteria where we joined a longer line of hungry short people. Malcolm was in line in front of me. He had just finished explaining how his aunt had bleached his name into the back of his new jean jacket. You do know that I didn’t ask, right? And to make shit worse the jacket was fly as hell.

Dominique was behind me saying, “…and her titty was on my shoulder.”

“The hell you talkin’ ’bout?” I asked.

“Crenshaw,” he answered. “She put her titty on my shoulder.”

“Eww. For what?”

“She was supposed to be helping me with the reading at my desk.”

I shook my head at how disgusting Crenshaw’s titties were.

“It feel nasty, too,” he continued. “And she stink, too. Smell like the chitlins soon as the lid come off the bucket.”

“Should have hit her in the face,” I suggested.

“I was ’bout to,” he lied.

I looked ahead to see that the line had moved forward but that Malcolm was too busy listening to Dominique and me to notice and step up. Nigga was a known snitch.

I waited until he had moved up to say, “Somebody gone do something to her ass.” “Ain’t it.” Dominique agreed. He always agreed with me because I was always right. I looked around the room watching the other classes where they all sat together. I imagined eating with the smart 5th graders. I knew where they were because I was in class with some of them before my exile to the retarded class years before. I watched as the smart boys whispered to the smart girls. The smart girls covered their mouths when they giggled. A smart boy caught me recklessly eyeballing the normal tables. He stared back at me. I looked down.

For lunch we had corn dogs, corn, mashed potatoes, a roll and a shallow puddle of yellow flavored pudding. I had eaten everything but the pudding when I heard Dominique say “…Ain’t it.”

I realized that Dominique had been talking to me. Probably for some time. Back then my short attention span and low impulse control had led to at least three fires set by accident.

Allegedly.

“Huh?” I said.

“I said, my momma probably be back home today, ain’t it.”

Dominique’s mother was a crackhead. ’86 was early in the crack epidemic for Virginia. Kids my age didn’t know much about crack, yet. We still assumed Nintendo was witchcraft.

“Where she be going?” I asked between spoonfuls of chalky pudding.

“To my grandma house. She live in DC. She sick.”

“She got the AIDS?” We didn’t know what AIDS was either.

Dominique shrugged his bone and leather shoulders staring into his spotless tray.

My eyes had already wandered off in search of unaccompanied corn dogs.

“Ain’t no food at the house neither,” he continued, eyes roaming far off trays.

“Oh yeah?” I wasn’t listening. I had some abandoned corn dogs in my sights.

“Ain’t no food when she there neither.” he said.

“What?” I was immediately suspicious. Mothers made sure their kids ate. It was the law. My mother made food appear out of nowhere for my brother and me. It was amazing. It was her superpower.

“She ain’t got no job. All she do is be up in her room with them men be coming ’round.”

I turned these facts over in my mind. I didn’t get anywhere so I asked,” How you be eating then?”

“Stealing,” he said.

I nodded in understanding. We all stole. For him it may have been survival. For most of us we just like to steal.

A bad idea slammed into my mind. “You seen Crenshaw took that bag of candy from Malcolm. It’s still in the closet.”

“He stupid,” Dominique said. “How he gonna try to sell candy right in front of her face?”

We shook our heads at Malcolm being dumber than both of us.

“It’s in there on the top, on the shelf.” I continued. ” I can’t reach it, but I bet you could.”

“Yep. I can reach up there.” He unfolded out of his perpetual slouch. “I can touch that shelf like it ain’t nothing.” He poked out his version of a chest, suddenly proud of his usually useless height.

“You better get that shit then. She probly had forgot it’s up there anyway,” I said. I could tell he was more scared than hungry. Stealing from a store was one thing. We got caught all the time. It was nothing. Stealing at school was a separate animal.

Dominique looked like he might not take my genius level advice, so I cranked up the temptation.

“It’s some fruit pies in there, too.”

“For real?” His mouth hung open. Direct eye contact.

I checked over my shoulder. Crenshaw and Malcolm were at the other table. They were both eating lunch trays. Sitting side by side they looked like mother and son gremlins.

“I saw ’em,” I said. “And it’s some mo’ stuff in there, too. Candy bars, too.”

“How we gonna get it?” he asked.

We!?

“All you gotta do is get it if she leave the room. She ain’t gonna know.” I said.

Lunch was over. Kids started to file past on their way out in that shuffling way that kids do when leaving the lunchroom for another room that definitely will not have any corn dogs or yellow flavored pudding.

The retarded class’s assigned seats were next to the exit. We always left the lunchroom last. They always whispered, pointed, giggled to one another as they walked by. The smart girls covered their mouths.

We understood.

“Okay, everyone. Time to go. Stack your trays on the table next to the garbage can,”

Crenshaw sang, while clapping her hands, and instructing us as if we hadn’t just seen half the school do this thing that we have all done every day.

Dominique hesitated as he left his tray on the stack. He was looking into the trashcan.

When I stacked my tray, I saw half a corn dogs on top of the trash pile. When I turned around Crenshaw was eyeballing me, arms folded under her gross boobs.

Did she hear me inciting Dominique to thievery? Did someone tell that quick? Had Malcolm learned to read lips?

Dominique crowded my heels all the way back to class.

That “We” shit.

He stared at the top of the coat closet as soon as we entered the room. The loot was in plain sight. Colorful candy wrappers showed through the thin, milky white, plastic grocery bag on the front of the one shelf. It was right there, a worm on a hook. I wondered why I didn’t just pull up a chair and get the bag for myself.

Damn it!

Five minutes after returning from lunch, Crenshaw announced that she was going to the bathroom. This became her routine. She would send me to fetch her water after late bell in the morning and she would go to the bathroom right after lunch. I was convinced that she would go take a wet dookie and not wipe or wash her hands. It just made sense.

“I’ll be right back,” she sang. “Don’t get out of your seat,” she finished before oozing out the door.

Dominique looked at me waiting for instructions.

“Hurry up!” I sort of whispered.

Mario looked back and forth from Dominique to me waiting for something.

Dominique sort of whispered back to me, “Look out at the door.”

Shit! Participation. That “We” shit got me in the mix.

I hurried to the door. Dominique was at the closet before I could look into the hallway for Crenshaw. He reached up and snatched the loot off the shelf easily. He stopped to look into the bag.

“The fuck is you doing?” I didn’t whisper. When I turned around to finally check the hallway I got a face full of flower-patterned circus tent.

Bitch forgot her big ass purse. Crenshaw stared down her greasy nose at me, shaking her head. “Go sit down,” she barked.

I scurried to my chair.

Dominique moved past my desk like a broken toy. One huge tear fell from his eye. I wonder if he was more afraid of the consequences of getting caught stealing at school or more hurt by the loss of those fruit pies.

Crenshaw stared threats at the class as she slowly pushed the closet door closed and ended with a shove to slam it shut. She took one more look around and then walked back out the door without another word, knowing that we all understood.

“Ooh. Y’all is in trouble,” Mario said. His face was transformed into a smile with a nose sticking out of it. No one delights in other people’s misery like children. “Y’all gonna get it. Stealing from the teacher. They gonna throw y’all in jail.”

Any other day I would have done something to scare him to show him I was bigger and so I was in control. This was one of those times I didn’t feel big enough to pull it off.

The day went on. Crenshaw avoided Dominique and me. Mario continued to make baby talk references to incarceration. Malcolm expressed his deep disappointment at us trying to steal his shit. He said it was okay though because he had more and then he named all the candy he had at home. Ain’t nobody ask.

As the clock ticked toward the freedom hour I started to entertain thoughts of clemency. I didn’t really have anything to worry about because I did not steal anything. When shady goings on were going on I was over by the door, not the closet. Why was I even worried in the first place?

Last bell rang. I put my notebook in my backpack, prepared to run.

“Shedrick and Dominique stay in your seats.”

Damn it! And why did she call my name first?

Crenshaw heaved herself over to stand in front of Mario’s empty desk. In the quiet of the deserted room the average height woman cast a long shadow. She folded her arms under her boobs.

She rained down judgement and superiority. Our eyes fell to our desks under the weight of it.

“What do you have to say for yourselves?” she asked. Neither of our heads raised. “I’m waiting.” she prodded.

On my periphery I could see Dominique’s bowed head rotate as he looked to me for guidance.

Mother fucking “We” shit!

“Shedrick?”

I fought the instinct to look up.

“Do you have anything to say for yourself?”

I could have said that I hadn’t stolen anything. I could have asked her why she held me after class when I wasn’t the one holding the bag. I could have lied and said I didn’t know what she was talking about. But all I could think about was running for my life through Blackwell Housing Projects when I missed my school bus home.

Crenshaw finally sighed and said, “I am very disappointed in both of you.” As if she knew either one of us, and “The two of you are my best students,” like she had anything to do with our accomplishments. “Now, I will see you both tomorrow. This will be your only warning. Straighten up.”

I watched orange carpet run until it turned into whitish hallway tile. Dominique called after me. I sped up. I had gotten in trouble because he was too dumb to just snatch a bag and go sit down.

I didn’t speak to Dominique again until Thursday. Then I had to pee.

The boys’ restroom at Blackwell Elementary was dark. It was lit from the sun through the high flat windows more so than from any lightbulb. And it stank. It had stalls for number twos and one long trough that sat in the floor at the bottom of the wall for standing number ones. The trough was not set deep into the floor so there was likely as many urine splashes on the floor in front of it and on your shoes then in the white metal basin.

I had just finished peeing when the spring-loaded hinges on the bathroom door squealed open. Three boys came into the bathroom. I knew bad was coming because I was alone, and they were together. They all looked right at me and nothing else as soon as they walked in, and I knew one of them.

“Look at this nigga,” Wee-Wee smiled. He was shorter than me, with an old man face. “I ain’t seen you in a minute, Peabody.”

I kept my eyes on the floor between us, as required. “I’m in LD now,” I said, showing him that I was not worth hassling.

“You in the retarded class,” one of Wee-Wee’s unnamed associates corrected me. He forced a fake bark of a laugh. His shirt was buttoned crooked.

The three boys surrounded me and took a few turns each questioning my intelligence. I stood my most invisible still in the dim, urine-scented cave, waiting for them to get bored. Bullies. Most times they just wanted to boost their own confidence by shitting on someone other. Then they would go away feeling better about their places on the food chain. It was always worse the more there were because they would all try to outdo each other. It was exhausting.

Wee-Wee took a step toward me. He spoke looking up at my ear. “I was in the class with this ugly ass nigga before. He ain’t never want to let me copy off his answers.” Which was true, and “He smell like piss every day,” which was not.

The two nameless boys took their step closer. “Why you ain’t let him see your answers?” asked Crooked Buttons.

“Yeah. Why you gotta be a little bitch?” asked the other nameless.

I was trapped. “I ain’t know you wanted to see,” I lied. Fear had me. I still thought I could get out of this stinking bathroom without being assaulted. I was mistaken.

Wee-Wee hit me with a quick jab. Surprised, I covered my punched lip. Wee-Wee seemed satisfied with the knuckle sandwiching he had served me. That was always their mistake.

In those days I threw all haymakers. Right, left, right, left hooks with all the power my rail -thin frame could put behind it. The first punch knocked Wee-Wee over against the wall above the trough. The second one dropped him into the warm, shallow puddle of unflushed trough. I fell to my knees pounding and cursing and crying. Wee-Wee was curled into a ball covering his old-ass face.

I was a dozen punches in when the nameless realized they were supposed to help Wee-Wee. Then I was on the floor curled into a ball covering my young face, again.

The bathroom door squealed. The sound of rubber-soled shoes retreated out into the hall and away. I peeked past my forearms. A kid was standing with his back to the door watching me. I jumped up and took my embarrassment with me out the bathroom door.

I was shaking. Quiet tears poured down my face. I always cried. I always let them say what they wanted about me but if they touched me, I always fought back. I always won. And afterwards I always felt like a loser.

THELONGESTHALLWAYONEARTH was empty. I was alone. My lip barely stung. What really hurt was the alone part. Wee-Wee wasn’t alone. When he was getting his old face bounced into my still warm piss he had someone there to help him up. When he ran someone was there running beside him.

A piano led a little kids’ class as they sang “B-I-N-G-O, B-I-N-G-O and Bingo was his name-O” as I turned the corner toward my classroom.

When I got back to class Crenshaw asked why I had taken so long in the bathroom. If I’d had a lead pipe in my hand, I might still be beating her head in today. Instead, I mumbled some lame excuse about poop and took my seat.

It was in the way that no adult would have ever ask Dominique why he was stealing food out of that closet. Maybe they would have found out he was an eleven-year-old forced to fend for himself but still showing up to school.

Mario asked me what was wrong because it was obvious that I had been crying, even to a baby. I ignored him.

Blackwell Elementary School was my 5th elementary school. My family moved once and was rezoned four times after that. Every new school was a different housing project that I did not live in. I was quiet. I was always a new kid. The bullies were all new. It was a never-ending cycle. By the 5th grade I didn’t know anyone but my brother, my mom and my grandparents.

My brother was two years older than me so during this time he was at another school. He was awesome. Everyone agreed. I was other one. But I had him.

Then he moved out of state to live with his dad.

I had my mother’s persistent depression. Her sadness came with constant reminders of how much she sacrificed for me. Mine came with the knowledge that she was right. I hadn’t met my pops yet. My grandparents were rich. They had a big house and three cars in a quiet neighborhood. We had heat sometimes.

I was always sad and angry except for when Ms. Brown smiled at me.

I didn’t raise my head until lunchtime.

I stayed a couple feet behind the lunch line. Dominique was next in front of me. He kept glancing back trying to catch my eye. I sat at the end of a nearly empty table. Dominique changed seats to come sit beside me.

“You want my Jello?” he asked.

I was immediately suspicious

“You don’t want it? It got the fruit in it.”

He shrugged.

It was a trap. If I excepted Dominique’s desert I would have to stop pretending I didn’t want to talk to him. There was no way I could keep pretending to be mad at someone who would give me their Jello with the fruit in it.

“What happened to your lip?” he asked.

“Nothing,” I grunted.

“Crenshaw put that bag of candy somewhere, ’cause it ain’t on the shelf no more.”

“Oh yeah?” I didn’t care.

“Bet her fat ass took it home.”

“Ain’t hers,” I threw in.

“Ain’t it” he agreed. “We ain’t even steal nothing. She the one stealing.”

“Ain’t it” I agreed. “I hope it’s poison in it.”

“Ain’t it. Somebody ought to poison her. That’s what she get for smelling like spoiled cat food.”

A bad idea exploded in my angry mind and fell out my mouth.

“I ought to do it, too.” I said.

“Yep. Do what?”

“I ought to poison her.” I said.

“Yep. That’s what she get,” Dominique said.

We sat in silence. That day the lunch trays had peas and carrots on them. Lots of trays still had both. Dominique and I plotted missions to liberate those peas and carrots with our eager eyes. We were two young buzzards sharing a branch.

“I’m gonna do it. I’m gonna makes her sick so she go. Then Ms. Brown can come back,” I said.

“You for real?” Dominique asked.

I didn’t answer. I was too busy plotting.

“It’s some rat poison at my house,” Dominique offered.

I shook my head at his stupidity. “That’s for rats. It ain’t gonna work on no person.”

We sat with our thinking faces on.

“Bet bleach make her get sick,” I said. “Bleach make anybody sick.”

“Yep. I bet it do, too,” Dominique said, just glad to participate.

I told Dominique I would bring some bleach to school the next day. He gave me nervous side eye. He nodded but didn’t comment.

When I was getting my assignments to do at my desk later, I didn’t dare look Crenshaw in her eyes for fear that the plan was so obvious in my mind that even she would be able to see it.

Friday is a Russian word. It means Freedom Day. School was mandatory like slavery. I think.

Our textbooks didn’t cover slavery. It did say lots about Lincoln, so I knew what emancipation was. Friday was a weekly Juneteenth.

To this day bleach still brings to my mind a white sheet hung on a backyard clothesline, its edges waving at the summer grass as a breeze carries the smell of clean clear across the street and beyond.

Unfortunately, that was all I knew about bleach on the day before my very first attempt to poison a teacher. Between that Thursday afternoon and Friday morning I picked up some helpful tips.

I learned that if you spend too much time trying to figure out how to secretly transport liquid bleach to school you will get a splitting headache. I learned bleach can eat through all kinds of plastic bags. I learned that mothers are made suspicious when sons are suddenly preoccupied with poisonous household chemicals. And I figured out that bleach will not eat a hole throughout aluminum foil.

So on the morning of my first conspiracy to overthrow a dictator I entered school and ascended the stairs up to the main floor with a teardrop shaped piece of aluminum foil filled with generic bleach tucked inside my white crew sock with the red stripes around the top.

That morning I moved slowly between the auditorium and the administration office down into THELONGESTHALLWAYONTHEEARTH. The flow of overexcited brown idiots was of no consequence to me that day. If anyone spoke to me or at me as I walked, I did not notice. I was focused on not spilling my secret potion.

I got to class later than usual. Dominique tracked me from the door. I nodded to him. He looked away.

I sat and waited to be called upon to perform my morning duty.

Every morning since Crenshaw showed up, she had sent me to fill her ugly ass Dallas Cowboys mug with water from the fountain upstairs. She said the one downstairs near my classroom door, wasn’t cold enough for her.

Over my shoulder Crenshaw breathed too loud. She shuffled papers around Ms. Brown’s desk. I wondered why she didn’t get water for herself before she came into the classroom. I imagine it was the same as all her other commands. She commanded because she could command.

“Here.” she said from behind me. When I looked back Crenshaw was holding that ugly ass mug out in my general direction. Her eyes were still on the paper on her desk. Like sit or roll over, “Here” meant do as you’ve been trained.

I climbed the stairs that blocked the retarded class door from the classroom across the hall. I expected the upstairs hall to be empty as always but instead the whole smart 5th grade class from above mine was in the hall with their teacher. The students were all in a line leading to their classroom door. The teacher was inspecting each student before allowing them to enter the class.

We all stole so much I didn’t question it.

I avoided eye contact as I walked past them. At the water fountain I took two long, slow drink. Over my shoulder I saw five students were left in the hall with the teacher. Their backs were to me.

I snatched the poisonous tinfoil teardrop from my sock. Three students and the teacher were left in the hallway. No one was looking my way.

I ripped the pointed end off the tinfoil. The acid scent of bleach jumped out at me. I poured the bleach into the empty mug, then added the water, then I gave it one quick stir with my finger. As I did this last I looked over my shoulder. Eyes were on me.

I fast walked around the corner into THELONGESTUPSTARISHALLWAYONEARTH. It was empty. I scurried to the nearest side stairwell. The potion sloshed onto my hand as I double timed it going down the steps. THE LONGESTHALLWAYONEARTH was deserted. I was alone. The sound of a little kids’ class singing about how they didn’t care that Jimmy Crack Corn followed me toward my classroom.

I peeked around the corner. The retarded class door was in sight. As I stepped into the doorway I almost ran into Wee-Wee. He jumped back when he saw it was me. I retreated back into the hallway so he could pass by where I could see him. His eye was black.

Wee-Wee hurried out and past me to the stairs. He smiled his wrinkled face smile as he climbed up and out of view.

I waited until he got to where he couldn’t spit on me, then I entered the classroom.

The other stupids were all at their desks, watching me when I entered. Crenshaw was seated at the crescent moon table. She didn’t look up when I approached. She extended her greedy hoof to the mug as soon as it touched the table.

I crossed my arms over my chest as she raised the portion to her thin, chapped lips. “Drink,” I thought at her.

She slurped like a moose draining a birdbath. Her gullet flexed. One swallow. Two swallows. Three doses of poison delivered. Success. So easy.

I turned my back to the doomed woman. Morning sun rays made a perfect yellow square of light on the carpet at the back of the classroom.

I strode past my classmates’ desks, head high, shoulders straight.

Dominique bit his lip as his wide eyes screamed at what he had just witnessed. When I looked over to him, he flinched and looked away.

Malcolm looked me up and down. A frown of envy turned the corners of his mouth down before he could stop himself. Having been caught, he hung his head to his chest in shame. Tears began falling into his open textbook. The sunlight rose up my body as I walked into it until I was submerged in brightness. It replenished me.

A scream split the still air. It was torn into chokes and gags. Mario began to cry a baby’s moaning cry of confusion and fear. Behind me Crenshaw was starting the last performance of her mean, insignificant career a teacher at Blackwell Elementary School.

I knew the warmth of the sun. It filled me as she struggled for each breath.

Mario’s panicked voice screeched from the hallway. “Help! Crenshaw need help!” No, little one. No help will come. Not for her. Not in time.

Mario screamed louder.

Sunlight touched my bones.

“It is done,” I declared.

A chair banged hard against a table. Hooves stamped the floor in frustration. Desk drawers were yanked open. I heard their contents fall to the rough cart. A fading buffalo convulsing as its feeble mind tried to make sense of what was happening. Crenshaw frantically searching for some relief from the ache that ravaged her turd-shaped body.

A desperate “Please!” croaked in my direction. I felt the single word flung over me like a noose over my head.

There would be no pleas heard today.

I raised my arms out wide over my head. I was the light through the window.

I turned around to survey my work.

The crescent moon table was askew. The blue chair lay on its side beneath it.

The teacher’s desk and the floor around it were littered with all manner of educational material. Crenshaw’s beefy calves/ankles and flat shod feet stuck out from behind the desk like the wicked witch of the west from under Dorothy’s house.

No one would be taking those shoes.

My walk back to the front of the classroom took half as many steps. Innocents hid their eyes from the radiance of my passing. Only Dominique raised his head to see above the cuff of my jeans. He stared at my poisoning hand. He awaited instruction. I had none for one so young.

As I approached the crescent moon table I entered a cloud of Crenshaw. Heifer farted on her way out. She was on her back surrounded by the scatterings from inside and on top of the teacher’s desk. Her face was twisted. Her tongue stuck out in one final grotesque scene.

At the closet I reached up to the top shelf, knocked Crenshaw’s big ass purse to the floor. I took hold of the hidden plastic bag of goodies. A blueberry fruit pie was delicious.

I carried my prize into the hallway. “Exit” said the sign above the door to my left. I needed no poofy coat. Out I went into an unsuspecting world. A world where the people would mistake me for a child until it was too late, and I ruled them as a king.

Had this story been fictional I could end like that. I could have ended it however I wanted. But this is a true story with a real ending, that went like this:

Everyone was looking at me when I entered the classroom. I looked to Dominique. He looked away. I had finally found the cure for that “We” shit.

Crenshaw was still at the teacher’s desk. She leaned all the way back. Her crossed arms sat under her boobs and on top of her stomach. A smirk played at the corners of her mouth. Her eyes were narrowed to knives.

A nervous “What?” escaped my scared lips. I was still standing two steps inside the doorway, thinking of running.

“You know what,” Crenshaw spat.

I knew not to respond to that shit.

Crenshaw pointed a Vienna sausage finger at the mug in my hand. “What did you do to that water?”

“Nothing,” I lied.

“Then tell me this,” Crenshaw said, “Why would Mrs. Johnson send someone all the way down here to tell me that some nasty little boy was putting his dirty fingers in my Dallas Cowboys mug?”

I bet Crenshaw left a bathtub smelling like hotdog water.

“Well?” she prodded.

I bet Wee-Wee was the one who really saw me. I bet he told Mrs. Johnson, and a million dollars says he volunteered to deliver the message to Crenshaw. One more name for the known snitch list.

“I don’t know what you talking ‘bout,” I lied. I was as angry as I was scared. It was in my voice.

Crenshaw leaned forward into my tone. “You better take that outside,” she said, pointing at the weapon in my hand. “And throw it out right now.”

Without another word I went out the door right then.

I stepped out into the morning cold of early January. It was that kind of cold that you’ve felt before and don’t know how you could have forgotten the feeling when you feel it again.

The concrete stoop was half in shadow as the low-hanging sun only just barely crossed over the roof of the building. I stopped the door from closing and locking me out by leaving my shoe in the breach. Frost twinkled on the broken steps. Every breath came out paused, floating white. Cars passed through the intersection.

Three steps down I felt the rocky asphalt of the fenced-in retarded class recess area. When I was still considered a smart kid, I went out the front door, across the street to the school’s gymnasium for recess. On warm days there was a big playground beside the gym for recess. There was space and grass.

On warm days or solid block of ice-cold days, whatever days we were allowed to go outside, the retarded class went out the nearest exit to fenced in blacktop. The view through the ten-foot-tall chain link fence was of a street corner surrounded by dilapidated, leaning homes, left to fill in the space between roach-infested project apartment buildings. The grass was the color of wheat. I watched junkies share needles through that fence.

I was still carrying the mug of tainted water as I stepped into the tepid sunlight.

The cold was inside my clothes. Bleach water spattered my one socked foot as I let the potion dribble out. Stray droplets splashed on the ground and turned to ice before they landed.

The world stopped, silent in one frozen, held breath.

An ugly blue star rolled up and over between me and the weak sun. I had thrown Crenshaw’s mug before I had known I’d wanted to do it. It rode a high swift arc up over the tall fence, then gravity spiked the ugly mug to bits and pieces and dust in the middle of the empty intersection.

“Take that outside,” she’d ordered. “Throw it out,” she had commanded.

I passed back under the glowing exit sign wearing the solid cold smiling, imagining Crenshaw tumbling over and over between me and the weak sun, clearing the fence before I had known I had thrown her.

No Comments