It is an unseasonably hot day in late January when I arrive at the Correctional Training Facility’s North yard for an interview with Travis, a writer, artist, and aspiring journalist who has been incarcerated for 15 years. I make my way through the crowded yard and the even more crowded cell blocks — this prison like so many others is hopelessly over its design capacity — to the seven-by-seven-foot cell Travis shares with another man. His cellmate is currently away, granting a modicum of privacy in a place inimical to such a concept. Just under 48 square feet, it is one of the smallest two-man cells in the state but, despite holding two beds, a desk, a toilet, a sink, and a pair of lockers, there is enough room to stand in the doorway to visit — barely.

Travis sits on the upper bunk beside an open-grated window through which drifts the sounds of men working out and playing soccer, boomboxes blasting tinny music, and the acrid smell of illicit smokes. The cell itself is clean if slightly cluttered, his locker mounted above his bed nearly full of books, folders and writing materials, as well as the staples of prison life across the country: coffee, Top Ramen, oatmeal, peanut butter, soap and toothpaste, colored pencils, and the week’s mail — a whole life vivisected and on display for any passing eye to judge at a glance.

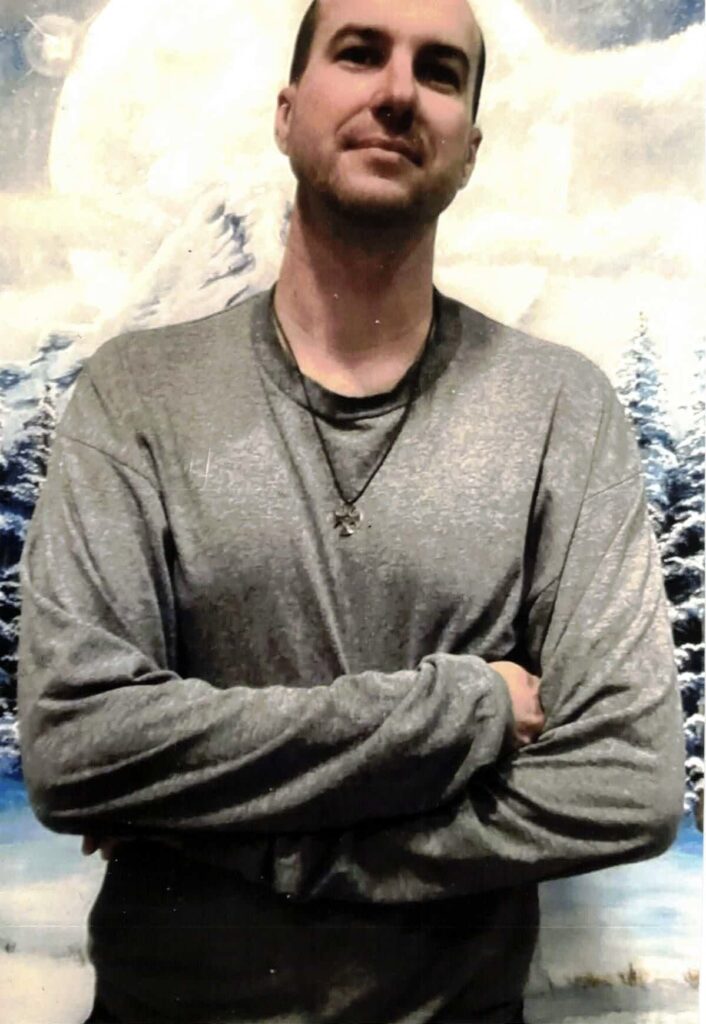

He greets me, a tall, lean young man with skin tanned from long exposure to California sun without the benefit of shade or sunscreen, his hair dark, cut short and receding even as it fights the incursions of grey creeping up his temples. He sits cross-legged and barefoot in shorts and an oversized t-shirt, the small fan at the foot of his bed barely able to keep the mounting heat at bay. His hands, arms, and feet all sport a number of dark tattoos, many poorly executed but unlike many I saw on my way in, none are gang related. He sees me cataloging his collection and offers a sheepish grin.

“Everyone in prison is inked. I don’t want to stand out.” And the old standby: “I thought it was cool at the time.”

“And now?” I ask.

“I still like tattoos . . . just not really these ones. There’s a tattoo removal program starting up here, but it’s only for people who are two years in the house or less.”

Travis is a lifer, convicted of multiple murders when he was 24 years old. He’s now about to turn 40 and whether he’ll ever be released is an open question. The intelligence in the dark eyes behind his glasses, the ease with which he smiles, and his openness make it hard for me to square the man sitting in his rolled-up mattress and eager to share his story with the portrait conjured by the old newspaper articles. I decide to dive right in: I ask him if he’s changed in the decade and a half he’s been in prison.

That easy smile becomes an earnest look of engagement.

“They said I had no soul. ‘Even as a child, I don’t think he had a soul.’ That’s in my probation report. They said it in court, in the victim impact statements, everywhere. That used to make me mad–like, I did some really awful things. But to say I don’t have a soul, that’s cold. I felt bad about what I did. I still feel bad. I think someone who had no soul would never feel bad about anything.”

“What do you think that means, a person having a soul?”

“I’m not religious, so I don’t look at it in a religious context. To me, when someone says a person doesn’t have a soul it means they have no conscience, or no empathy. No heart. They only do things for themselves, and it doesn’t matter if their actions hurt someone else.” He frowns. “Shit. Maybe they were right, because that’s how I used to be.”

“But something changed.”

“It did. Only it wasn’t any one thing or any one moment. After the shock of everything wore off, and after I stopped taking the psych meds I was using to mentally check out, I felt a lot of things. Scared. Angry. Sad. I really hated myself. I hated that everything I didn’t like about my life had come from my own actions. Once I wasn’t high all the time, it was too obvious for me not to see that connection. And once I saw it…”

“You couldn’t stop seeing it.”

“Exactly. Which sucked.” He laughs. “No, I’m kidding. But I was really depressed at the time, because realizing everything was my fault meant that I had to do all the work myself if I wanted anything to be different. No outside interventions, no quick fixes, no magic pills.”

“No easy way out.”

“No easy way out,” he sighs. “So that was a seismic shift. I never did anything the hard way. If things were hard I cheated, or I quit. But — I mean, I can’t quit on being alive. I didn’t want to die.”

“Was that because of your time in the prison mental hospital?” Travis had spent several months in and out of the hospital ward where the mentally ill prisoners were housed when he first came in — an isolated, dirty, terrifying place to hear him tell, it was even comparable to a regular maximum-security prison.

“No. I had already decided not to kill myself before all that. I was just looking for a place to hide, another quick fix. I was really afraid.”

“Of prison?”

He nods. Then, “No. Of myself. Like facing who I really was.”

“So, what changed? What gave you the strength to stop running away?”

He looks to the end of his locker where a collection of photos is secured to the metal with broken pieces of magnets just large enough to keep them in place. Among the images I see in this makeshift altar are at least a half a dozen cats, a brown-haired woman in a parka, a card certifying that Travis has been afforded the privilege of participating in the prison’s hobby craft program, and other bits of ephemera gathered along the lonely journey of incarceration.

“I was totally alone. I’d been on my own for my whole life. I had an awkward, distant relationship with my family growing up. I didn’t meet their expectations at all. I disappointed everyone. At least, that’s how I felt. I didn’t have many friends and I didn’t fit in in school, so I always felt like an outsider. Prison just took that to a whole other level.”

He pauses, considering his words.

“I always made everything about myself. That’s all I ever focused on. I took the whole world personally. Like it existed just to make me feel bad about myself, to show me what a loser I was. But that’s stupid. I believed a lot of stupid things. The more I had to spend every day with only my own company, the more I started to see that I was irrelevant to the world. I didn’t matter at all, and my life didn’t matter. If it was miserable or not, that was all on me. If I wanted things to be different, I had to be different. I had to create the life I wanted to live–nobody was going to do it for me.”

“That sounds . . . massive, ” I say. “How do you even approach such a total shift?”

“Ah . . . by messing up, a lot.” He shakes his head. “Really, by learning from my mistakes instead of just reacting emotionally, to the embarrassment of failing. Like, I used to make a lot of smart-ass comments because I had zero social skills. So, I reverted to what I know, being a jerk. It was a defense mechanism for when I felt uncomfortable, a way to keep people away because I was afraid to trust anyone. But nobody likes jerks, so I’d make a smart-ass comment, then someone would get mad. Then I’d get mad, and I’d just end up being the jerk that everyone was mad at. It sounds basic, but this was how far back I had to go to get away from

my bad habits and wrong beliefs. After a while, I started to make the connection and see that when I wasn’t being an asshole, I could have honest conversations and even make friends.”

“Was there any particular friend who really stands out to you?”

“The first person I would really consider a real friend was this guy named Rex, but everyone called him Squirrel. He was big he looked like one of those mountain men, or a Viking –long, crazy hair, big beard, as tall as me but built like a linebacker. He used to work for Brinks, the armored truck company, and he said that he got that build from slinging huge sacks of quarters around all day. He had a big personality, too.”

“How do you mean?”

“Squirrel used to joke that if he was evil he would make a great cult leader. But he had a good heart, and this powerful charisma. Everyone liked him and he got along with all the different cliques on the yard. He had all the people skills I didn’t, and that’s what really made me want to get to know him. The first time we met I was a jerk, but instead of getting mad he made me laugh. Squirrel was the first person I met in prison that wasn’t either standoffish, or negative, or aggressive, or abrasive. Our society really hammers that belief, that to be a man means never being open or letting yourself be vulnerable. In prison it’s ten times more. People develop a hypersensitivity to perceived threats – the slightest hint of disrespect can cause a fight, the barest whisper of weakness or just being different makes you a target. To avoid all that, you just shut down. Don’t even have feelings, just shove everything down so deep you go numb.”

“It sounds like you’re speaking from experience there.”

“That’s the reason I’m in prison. That’s the root of all the choices I made and how I came to believe I had no other options. I crammed all the hurt and shame and rage from my whole life down and never faced anything. Eventually I ran out of room. My feelings became too big and toxic to bury.” Then he makes a fist, then splays his fingers, “Boom.”

“Yeah Like a nuclear bomb. A chain reaction of every terrible thing I’d ever thought or felt or believed all building on itself and devastating my life. I mean, it was all me, I did that, but I don’t believe it was preordained. If I would have dealt with my issues as they came instead of trying to hide from them, I don’t think I would have ever hurt anybody, or killed them.”

There’s a long moment of silence as that sinks in. Travis gazes out the window, the memories difficult to face even after years of practice, years of not hiding. Sometimes in our lives we have wounds, he told me once, but healing isn’t about undoing the hurt. We have to tend to our wounds, so they don’t get infected and poison us, but our scars, like our past, aren’t something to be ashamed of. Once he looks back to me, he smiles again. So do I.

“So, Squirrel.”

“Yeah–Squirrel. He had this way about him, this openness, this confidence that wasn’t arrogance. I thought he had some secret when we first met and I wanted it, that deeper insight that let him rise above all the normal prison bullshit. Later I found out there was no secret, no trick; it was just that he’d gone through all the same traumas that most of us had, and he’d made the same choice to be better, to be different, to forge a path to a life that didn’t make him miserable. He’d been doing it longer, is all, working hard at something important to him whether or not he screwed up sometimes.”

“Is there something specific you learned from him that you’d like to share?”

“What I learned from Squirrel could fill a book. He was like Life 101. He taught me to come out of my shell and talk to other people. He was involved in all kinds of things. He invited me to play Dungeons and Dragons with his group, a sort of neutral nerd zone in the drama of prison politics. He brought me into the Druid circle, where they talked about nature, and spirituality, and philosophy, and the environment, and mythology, and animals and all kinds of things. He fed me all the books I could read and talked to me about what they meant. He taught me about writing, and about how to tell stories, and about how to listen, and how to meet people halfway. He taught me how to navigate the bureaucratic nightmare of prison, so my rights don’t get trampled, but also so I don’t annoy the staff with petty complaints. He taught me how to stay out of trouble — the real way, not just getting caught — and how to sew, how to cook, how to landscape.

“It sounds like he was a hell of a teacher”

“For sure. But the main thing Squirrel taught me was how to be myself, and not be afraid to let those walls down. That led to being honest, understanding myself, and having integrity. That was a strong foundation for me to build on, and I still do every day. That’s how I stopped hiding, by discovering real connections with other people and discovering a purpose for living in the world besides just selfish ones.”

“All because you met a squirrel.”

Travis laughs. “Yeah — I met a squirrel in prison, and I found my soul. It sounds like a fable. But that’s my story. That’s what saved my life.”

No Comments