Summary

This story is one that is true. It tells of a pivotal moment in the incarcerated life when hope hinged on my will to survive amid the chaos. Throughout this period, I was still shaking off the drunkenness I felt following being sentenced to prison. I know this may sound like a cliche, but I come from a long line of people who managed to live among adversity their entire lives, for so long that it created a new base within their DNA. I was the recipient of knowing adversity, but I did not want to become its victim. So, challenging my conviction was a way I was going to fight, and supplicate relief for the errors that occurred during my trial. But in 2011 it was going to be my first time actually challenging my conviction. Most times pro se litigants challenge their convictions simply to get their convictions overturned but, in 2011, all I wanted for is to be successful at appropriately filing the appeal. I remember the emotion I had till this day when I got the news the appeal was filed. It felt as though the court had granted my release. So, I hope you enjoy this piece and look forward to your feedback.

2011 would be a year I will never forget, because that year brought with it experiences any novice to prison life would never have imagined they would experience. That was me. For instance, that year a riot erupted inside of the prison I had been classed to. Some may not have seen it as a riot but rather a small rebellion of six hundred of the three thousand prisoners at the facility. But in my eyes, it was more; it was more because no one was in control of the chaos—not staff or prisoners. Anything could have happened–death, hostages taken, and even an escape plot. Fortunately, nothing of that nature transpired because I did not want to spend six months on lock-down.

That year I also encountered my greatest adversary after receiving a judgment from the appeals court denying the claims in the appeal of my convictions. The news did not embitter my emotions, that certainly didn’t escape me. One reason for that is I was represented by a public defender. And this isn’t a knock on all public defenders or their abilities, it’s more of a knock on the system that doesn’t afford indigent defendant’s a fair shake during trial and on appeal. You see, public defenders in most counties around the country individually represent over one hundred and forty clients at a time. Their caseload in a month will likely surpass what a single assistant prosecutor handles in three months. There is no way possible any one person can read over seven hundred transcripts and go over a mountain of evidentiary exhibits, and in the same stroke prepare legitimate arguments for an appeal, then proclaim to be efficient when representing one hundred and some-odd other clients. It’s not humanly possible. Half-stepping is bound to permeate efficiency somewhere.

It became clear to me that the state (prosecutors) was not the only adversary when a defendant or appellant files their appeal to the courts. That year I encountered a few other guys who were being represented by the same appeals attorney who was representing me. Their briefs contained little to no arguments which could afford them a chance for remand. I would also come across men from different parts of the state who would complain about the arguments their appeals attorney raised in their brief. In each case one claim always arose: “The evidence presented at the trial is against the sufficiency and manifest weight of the evidence.” Sounds like a reasonable argument, right? What a person on the outside of the justice system looking in may not know is this is a scapegoat argument. You see lawyers know this claim isn’t cognizable in federal habeas appeals, and their efficiency for putting little effort in raising such an argument doesn’t raise any red flags to any appeals court. Courts tend to see these arguments, or grant attorneys the benefit of the doubt by insinuating that their decision to raise such an argument was purely strategic.

Unfortunately, I too was the recipient of an attorney who poorly argued a manifest weight argument, and the state immediately pounced on my appeals attorney’s flawed argument. The state argued that the appellant (me) makes mention of one charge, but no mention of the other charges associated with the case. I had to admit, that made sense. If the state asserts that each charge was committed in the commission of another a defense attorney, or rather in this case, an appeals attorney is required to challenge each charge on appeal as if it is one charge. So, is it a coincidence that my attorney argued this claim with little enthusiasm in presenting the argument? I doubt it.

Following the conclusion of my direct appeal the public defender’s services concluded that in Ohio, and I’m sure the same apply in other states, once a decision has been rendered on a direct appeal in the case of an indigent defendant the appeals attorney no longer has an obligation to represent the defendant.

Unfortunately, this process tends to create a slippery slope because, unlike your direct appeal in a trial court, the court doesn’t have to inform a defendant or an appellant they have the right to appeal to the next court, nor does an appeals court have to inform one of trying to appeal the appellate court’s decision to the Supreme Court of Ohio. Due to the unjust fact that this notification isn’t a prerequisite many indigent appellants aren’t aware that they are able to appeal a previous decision to an even higher court. I was one of those indigent appellants.

I had no idea where to bring up the errors I believed took place at trial—or, more accurately, to bring up the errors my appeals attorney thought had occurred during trial. Fortunately for me I did not give up easy. The rejection and cluelessness encouraged me. I wanted to learn what my next step was. It didn’t take long for me to find out what this step was.

Thanks to several United States Supreme Court cases I would come to learn that prisoners in my position possessed the right to access to legal material and access to the courts. See Bounds v. Smith (1977). This was a relief. Now Lebanon Correctional Institution is one of the oldest prisons in Ohio, standing since the ‘50s. In one unit its tiers held one hundred inmates on each of the three abodes of desolation. The cells were the size of janitor closets, and it was host to several species, from humans, mice, roaches, and rats. To some this was torture, to me it all felt more like a bad dream that would eventually change. The water from the tap ran a brown slick silk that was physically visible underneath the carwash showers. I had no choice but to accept the fact that this was my new life, but I maintained the idea it would be a by-product to my freedom, and I’ve maintained that ideology in every institution I have stepped foot in.

On the left hand-side of the football length hall was the library. It possessed an array of literature; it was the first place I discovered Langston Hughes and his extirpation to France, a place that then truly implemented the tone of freedom. Within the library to the far corner was another room. A row of eight computers lined the wall and a myriad of law books lined the shelves of a seven-foot bookcase. This was surreal because prior to my trial access to such resources never crossed my path. Today I know it was meant for me to be disadvantaged for the sake of the prosecutor. But there I stood in the law library’s doorway staring at endless possibilities. You see, I did not see computers and books, I saw hope.

Prisoners with the title of legal clerks were the ones who typically assisted other inmates like me with questions regarding steps to take on their quest of litigation. The clerks weren’t certified paralegals, or ex-lawyers, they were just empirically adept from their decades of incarceration. But when it came to some clerks being helpful, it was an overstatement.

The first clerk I approached was a balding black guy. I thought because he was older certainly it would pain him not to help a clueless youngster. But this was not the case.

“Excuse me,” I approached his table.

Over his thick-rimmed eyeglasses he gave me an intellectual stare. “Yes.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but I was hoping you could provide me with some direction regarding my appeal,” I said. He went back to the legal news article in front of him without answering me. I didn’t know how to take this. I unfolded the paper in my hand and produced them. “You see here –”

“You can’t afford me,” he stated candidly. This time he wasted no time with my woes.

Here was a guy wearing the same color clothing that I was, addressing me as if he had a caseload with over one hundred and forty clients. But he must have been confused to think I was asking that he write the appeal up for me, because I had every intention of doing it on my own.

After asking the first legal clerk for help I asked the second of them and it was there I received my first yes. He went over the rules governing the Supreme Court of Ohio. The first thing he revealed was for me to perfect an appeal to the Supreme Court of Ohio, I would have to mail into the court a Notice to appeal, and my appeal brief together within 45 days of the judgment entered by the appeals court. So immediately after to the best of my ability I completed the Notice and brief. The next step was to wait to receive a filed stamp copy of both documents I had submitted, which would inform me that my action was under consideration. Two weeks later I received the copy, but it wasn’t the response I had been seeking. The Supreme Court of Ohio’s clerk informed me that because my brief exceeded the fifteen-page limit it did not comply with the court’s filing requirements and therefore, it could not be filed until I made the appropriate correction. I couldn’t believe I had not been aware of this. I couldn’t blame the clerk, he had provided me direction, but he wasn’t obligated to hold my hand as I earnestly typed up my arguments. But I was not deterred.

I had only gone over the page limit by two pages, there was nothing to panic about. The clerk suggested the error to be fixed, so that’s what I did. The next day following the notice from the clerk I was back in the library editing my first brief with little confidence, a confidence which had been depleted by the return of the appeal I had submitted. Nothing could ever prepare someone for the feelings I had incurred.

Now because the appeal was overdue there was another layer I was now required to incorporate in the filing, a motion for delayed appeal. This time I did my due diligence, going over this Supreme Court Rule, I learned it wasn’t difficult to follow. In two days, I incorporated the new motion and shaved two pages off the brief without greatly affecting the arguments to my claims.

Only three days had gone by, I recall, after mailing the brief and the other attached filing when I found myself anxious. The previous circumstance with the return of my brief prodded me with the question of “What if you messed up again?” and it was menacing. I couldn’t answer the question. From what I knew at this stage of my incarceration, other men had found themselves in similar predicaments and it was there that they buried their Pro se litigating practices.

Somewhere internally, in the mushy sensitive parts of me, there was hope hammering at my abuser—pessimism.

Eight days had gone by since mailing the brief and the other documents. I was called into my case manager’s office. He pointed at the seat to my left.

“Have a seat,” he said. If he were ever to become a principal in the future, he would make a dang good one. Because as I took the seat, I felt like a child in elementary ready to be disciplined for something I had done. He passed me a piece of paper that had been lying on his desk. “Sign it by your name,” he said. Then he asked: “What’s your prison number?” It was procedure to ask.

“562-207,” I replied. Following the confirmation of my prison number the case manager scooped up a packet inside of a manila envelope, clipped its seal, checked the contents, and passed me the packet.

“It’s legal mail.” The suspense had already been tense because of his peculiar demeanor, but his mention of it being legal mail and the huge font of the Supreme Court of Ohio’s name on the mail made the moment even more tense than it had already felt.

Back at my cell on the third range of the unit H block, I stared at the manila envelope that I sat atop my fifteen-inch television. The room was quiet beside the old, frustrated pipes inside the wall of the cell. I had a debilitating apprehension to open the manila envelope and read the contents for I knew another rejection would only determine if I would end up like the many who gave up at this point. They will never be able to call themselves a pro se litigant, because if you never see that motion or brief stamped with the word filed, you’re just another attempter.

Then and there I decided to prosper over the pessimism and hammer down its rusty negativity into my mushy and sensitive board of hope. I snatched the packet up off the television, removed the papers inside, and for a moment I stared at the paper itself while every bit of my visit, its periphery, and the waning focus from irrelevant details. My eyes adjusted through the watery fluff of unfailing tears and read the words within the dried paint of a four-inch square: “FILED.”

Piece of cake, I thought.

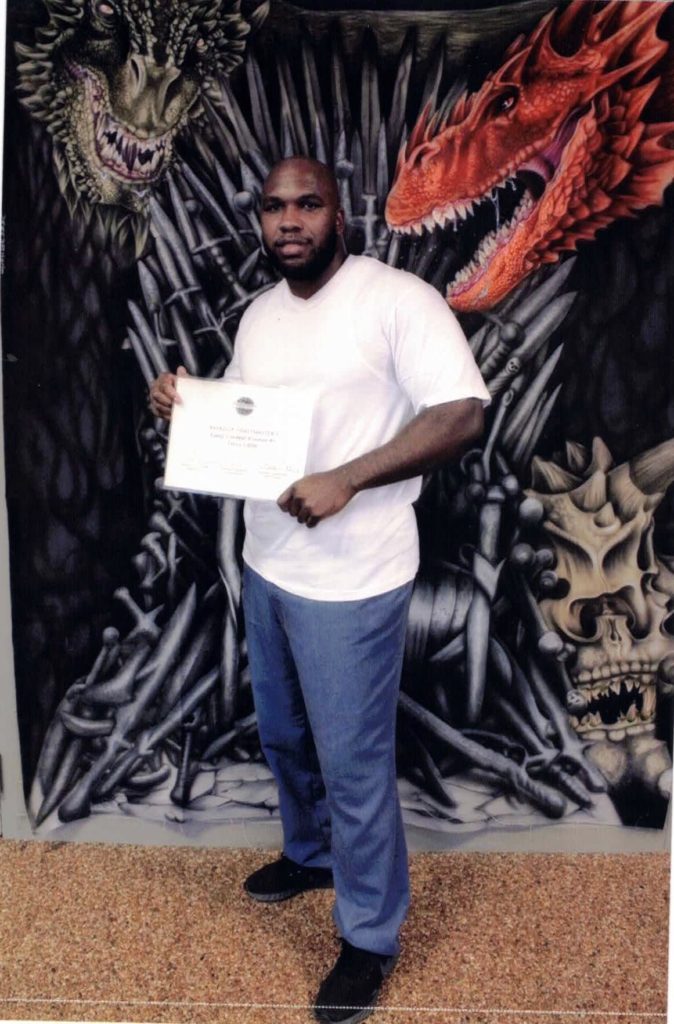

I was now officially a Pro Se litigant.

No Comments