I was watching the movie “Shawshank Redemption” the other night and was struck by what the old black convict, Red, said to Andy Dufrane, the innocent man convicted of murdering his wife. “Hope,” he declared, “has no place for a man on the inside. Hope can drive a man insane.” At the time, a small part of me wanted to agree with this sentiment; the part of me that suppresses emotions like longing and affection in order to avoid disappointment and rejection. But as I thought about his words, I envisioned all of the men that I know who have lost hope. I know men who have become mere shadows of themselves, who have forsaken the idea that they can or should strive for anything worthwhile, and have lost any conception of what is truly worthwhile, I know men who have turned into beasts, lashing out at the world in their frustration and pain, returning to segregation again and again. I know men who have coped with confinement by turning their backs on the world outside, yet have slowly died inside as the years have gone by. Hopelessness has transformed all of these men in ways that they could never have foreseen, and would have never imagined. Andy Dufrane was right. Hope is a good thing. Maybe the best of things. Hope is the one thing that should never die.

I have hoped for many things over the years that I have been confined. I hoped that I would be able to protect myself when, at age 15, I entered the Department of Corrections. I was. I hoped that years of imprisonment would not change me into someone who lacks compassion or compunction. It didn’t. I hoped that I would get an opportunity to earn a college degree. I did. I hoped that laws would change so I could have an opportunity to be released. Finally. They are.

In spite of my circumstances, I never gave up. I never lost hope. However, in retrospect, I realize that my resilience, most likely, does not stem from some innate quality that enables me to persevere. I simply have been more fortunate than others. I have a family that has remained supportive throughout decades of confinement; other prisoners were abandoned by their loved ones long ago. I have a support network that would enable me to seamlessly transition into the community; countless other prisoners will be homeless when they return to the streets. Although I never gave up, circumstances outside of my control kept my hope alive. Unfortunately, for too many of the men and women confined, there is no reasonable basis for them to feel hopeful. When the present is miserable and the future looks bleak, it is natural that one would succumb to feelings of despair.

So the modicum of hope that I have is probably due to the fact that, even with a life without parole sentence, my life of confinement has not been as dreadful as the lives other prisoners have endured, and my future prospects are more optimistic than dozens of other men I have come to know.

My friend Baca killed himself next door to me in segregation. He was 28 years old, had been incarcerated since age 16, and had a prison sentence that was so lengthy it amounted to a natural life sentence. Over the last decade, almost all of his family had moved on with their lives: the lone holdout was his sister. For weeks, he had not been able to contact her. The letters that he sent to her kept getting returned, with the red, pointing finger emblazoned across the postage stamp indicating that the letter was either undeliverable or the resident no longer lived at that address. Her phone also seemed to be disconnected, yet it was impossible to determine due to the prison phone system. On his behalf, I had my brother look into it and he learned that she had moved without leaving a forwarding address. When my brother told me the news, I reluctantly informed Baca. There was no way to soften the blow. It was around 3:00 pm. Less than twelve hours later, Baca was dead.

I wish Baca had never lost hope. The very same legislation that could set me free for a crime I committed at age 14 would have given him an opportunity to be released too. I truly wish his potential could have been fully realized, and the judge who had sentenced him as a teenager could have seen the man he had become decades later. As far as I have come since the days when we were neighbors in Maximum Custody, I have no doubt that he too would have grown into someone who is respected for his intelligence and humaneness. But his potential will never be realized. So all I can do is fondly recall the man, lamenting the fact that he will be remembered, instead, for acting ignorant and being ruthless.

Three acquaintances of mine have been serving life without parole sentences since they too were juveniles. The difference, however, is that each was convicted of multiple counts of murder, and the sentences for each count must be served consecutive to one another. Although adolescent brain development research demonstrates that the heinous nature of such crimes are not, in and of themselves, evidence that any of us were irretrievably depraved minors whose characters would never change, these mitigating factors will have no bearing on the ultimate fate of these men. Even if they are resentenced to terms that allow them to, theoretically, be paroled, they will remain imprisoned to serve the consecutive sentences imposed. While I have reason to be hopeful this legislative session, due to the fact that the most punitive bill relating to juveniles allows for parole after serving 30 years, these men would be long dead before their sentences could ever be completed.

I began to think about all three of them as I was rereading my last MB6 essay, Afterlife. When I finished reading, I felt ashamed. While I was worrying about when I would be free, knowing that I would, in all likelihood, one day be freed; these men have had to, once again, come to terms with the idea that they will never, ever, be freed. They know full well that forthcoming legislative changes will alter their sentences in name only, removing the label life without parole yet ensuring that they remain imprisoned for the rest of their natural lives. I have since stopped bemoaning my situation.

I never had the chance to tell Baca not to despair. I never knew just how utterly despondent he was. This time, I can easily imagine how dejected my acquaintances must feel knowing that, in spite of the invalidation of their sentences, the prospect of spending the rest of their lives imprisoned still looms before them. Lest they, or any other prisoner in similar circumstances, get Baca-like thoughts in their heads, know this: lawyers are already arguing that there is no constitutional distinction between sentencing a minor to a mandatory term of life without parole and sentencing a minor to a term of imprisonment that is, due to its length, functionally equivalent to life without parole. Research has already ended the practice of sentencing minors to death, brought forth a categorical prohibition against sentencing youths to life without parole in non-homicide cases, and eliminated mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles convicted of homicide. So, to Blade, Dave, and Bear, nil desperandum: do not despair. For all those prisoners who have hoped for so much (or so much less) and gotten so little (if, indeed, anything other than heartache), never despair.

|

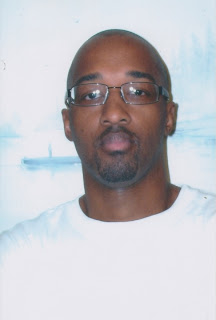

| Jeremiah Bourgeois |

Jeremiah Bourgeois #708897

Washington State Reformatory Unit

P.O. Box 777

Monroe, WA 98272-0777

USA

No Comments