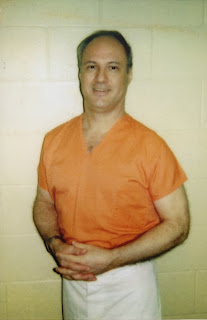

By Michael Lambrix

(Written August 2017)

Our beloved Mike was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017. To honor his memory, we share with you this essay he wrote eight weeks before his execution.

“Dr. Edith Bone has decided not to cry. On this autumn afternoon in 1956, her seven years of solitary confinement have come to a sudden end. Beyond the prison gates, the Hungarian Revolutions final, scattered shots are echoing down the streets of Budapest. Inside the gates, Bone emerges through the prison´s front door into the courtyard´s bewildering sunlight. She is 68 years old, stout and arthritic.

Bone was born in Budapest in 1889 and proved an intelligent – if disobedient – child. She wished to become a lawyer like her father, but this profession was closed to women. Her options were school-mistress or doctor; she accepted the latter.

The Great War began soon after her graduation and so she went to work in a military hospital. Perhaps it was there, seeing the suffering of the poorer classes, that her communist sympathies bloomed; she watched an illiterate soldier, a shepherd before the war, as he cried at the window, cradling his shattered arm and worrying about his lost children. He was only one broken man among many.

After the war, Bone devoted herself to political work in England for 16 years, and it was this foreign connection that would excite suspicions of authorities when she returned to communist Budapest in 1949. Secret police stopped her at the airport on her way back to England.

Inside headquarters, a slim man presented himself, decked in fine clothing and smooth manners. He took her into his little office and told her they knew she was a spy, an agent for the British Secret Service. “Until you tell us what your instructions were, you will not leave this building.”

Bone replied, “In that case, I shall probably die here, because I am not an agent of the secret service.” What followed – her seven years and 58 days of solitary confinement – is the stuff of horror films. She was held in filthy, freezing cells, the walls either dripped with water or were furred with fungus. She was generally half-starved and always isolated except when confronted by guards. Twenty-three ill-trained officers interrogated her with insults and threats – once for a 60 hour stretch. For one period of six months, she was plunged into total darkness.

And yet her captors received no false confessions, no plea for mercy; their only bounty was the tally of her insolent replies. It became a kind of recreation for Bone to annoy the prison authorities on the rare occasions when she saw them.

But Bone´s most extraordinary strategy was not the way she toyed with her captor, it was the way she held sway over herself – the dogged maintenance of her own sanity. From within that forced void she slowly, steadily, built for herself an interior world that could not be destroyed or stripped from her. She recited poetry, for starters, translating the verses she knew by heart into each of her six languages. Then she began composing her own daggered poems. One, made up during her six months without light, praised the saving grace of her “dark-born magic wand.”

Inspired by a prisoner she remembered from a Tolstoy story, Bone took herself on imaginary walks through all the cities she´d visited. She strolled the streets of Paris and Rome, and Florence and Milan: she toured the tier garden in Berlin and Mozart´s residence in Vienna. Later, while her feet wore a narrow furrow into the concrete beside her bed, she set out in her mind on a journey home to London. She walked a certain distance each day and kept a mental record of where she´d left off. She made the trip four times, each time stopping when she arrived at the Channel, as it seemed too cold to swim.

Bone’s guards were infuriated, but she proved proficient in the art of being alone. They cut her off from the world and she exercised that art, choosing peace over madness, consolation over despair, and solitude over imprisonment. Far from being destroyed, Bone emerged from prison, in her own words, “a little wiser and full of hope.”

|

| Michael Lambrix was executed by the State of Florida on October 5, 2017 |

5 Comments

BlueJeans2004

October 6, 2018 at 5:05 pmThis is such a moving article he had written. I do believe there is absolutely no God-given logic to a system that imposes long term suffering on a group of individuals that God himself loves and created in His image. A portion of the voting race can't look past judgement to embrace the possibility that guilty or not – every human life has value and should be treated as such. My only solace in their suffering is that on the other side, the memories of this hell hole will fade quickly and they will only know peace and every spiritually good thing they were denied in this life. (Not to dismiss the pain and suffering of the victim's families who are in need of incarcerating someone to put their fears and anger to rest) Guilty or not – I truly don't believe this is the answer. I can't imagine the depth of their suffering and pain. My stomach is sick that is justified punishment in too many places. Love rehabilitates, not hate and murder. "Judge not, that ye be not judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you." I live in fear of the Judge who will show me no compassion if I withhold compassion from His creation. And yet, people of faith even hold fast that they're doing God's work in these executions. I don't have to have others agree with me to know fully and completely that this is WRONG. Reach out to an inmate and build a friendship with a human being, mistakes in their past or not, they need us to love and support their mental health and to provide HOPE in a place where HOPE is seldom found.

Unknown

October 5, 2018 at 11:51 pmI really liked to read Michael's articles. He was a gifted writer, and he was perhaps my favorite writer on the site.No matter what happened in the past, he did not deserve to be executed.No one deserves to be executed, no matter the crime. His execution seemed to be particularly unjust and arbitrary, in that if he had pleaded guilty, he would now be living in the 'free world' having served his sentence. The death penalty is an unjust and cruel punishment. May he rest in peace.

Anonymous

October 5, 2018 at 9:35 pmI found mb6 just over a year ago. In fact, it was Michael's writing that led me here. I knew nothing about death penalty. I was captivated by these writers, especially Thomas and Mike. I started out as an anonymous reader, but Mike's execution was the final straw, the immediate trigger for certain actions that I took, a year ago.

For those of you who loved him, please know that his death, painful as it was, was directly responsible for something amazing that had, and I know will continue to have positive ramifications for decades to come.

RIP Michael. I'm sorry for what you had to endure. Your pain was my inspiration.

Joana

October 5, 2018 at 7:28 pmI felt and still feel a great remorsement because he told me to read his blogs…once he answered me back ….I wrote him a letter….in fact….I do not like so much reading for a long time….and I only was foccused to sign a petition to the governor so that he were not executed….I have now read his blogs and I have realized how unhappy his life was.and at last as I did not know he had a facebook page…but I had time to write something for him…and He saw it….before being executed…I still feel upset about his death…..and about the unfair american system… I hope Jesus Christ will reward him with lots of blessings and he will have found the heavenly peace as he could not have on the earth….Thanks MICHAEL…I did not know you…but you were good….

CS McClellan/Catana

October 5, 2018 at 4:08 pmI hoped that the one-year anniversary of Mike's death wouldn't be passed over, so thank you, MB6 staff. One year isn't enough to soften the pain of losing him. And it certainly isn't enough to come any closer to accepting official murder as justice.