“Okay,” I breathed into the home-made microphone, trying to imbue my words with an added dose of solemnity. “Rabbit, I hope you understand what exactly is at stake here.”

“I do,” he responded, equally grave.

“I don’t understand why he–” Rod tried to interject, before I cut him off.

“The Wheel has spoken. Don’t complain to me – talk to the Fates.”

“Will the record note my object–”

“The record will so reflect,” I shot back. “Now, Rabbit, here is your question,” I said, turning the card over. “What is the sacred animal of Thailand?”

I was in the process of giving my best Bond villain laugh when Rabbit spoke up: “It’s a white elephant.”

I cursed. “You don’t even know how to spell bloody Thailand, how the fuck could you have possibly known that?”

“I went there for R&R when I was stationed in Japan with the Marines. Even got drunk at a bar called The White Elephant. You wouldn’t believe what the hostesses will do if you –”

“Oh!” Rod shouted. “In your fucking face, Alex Trebek! Hooah!”

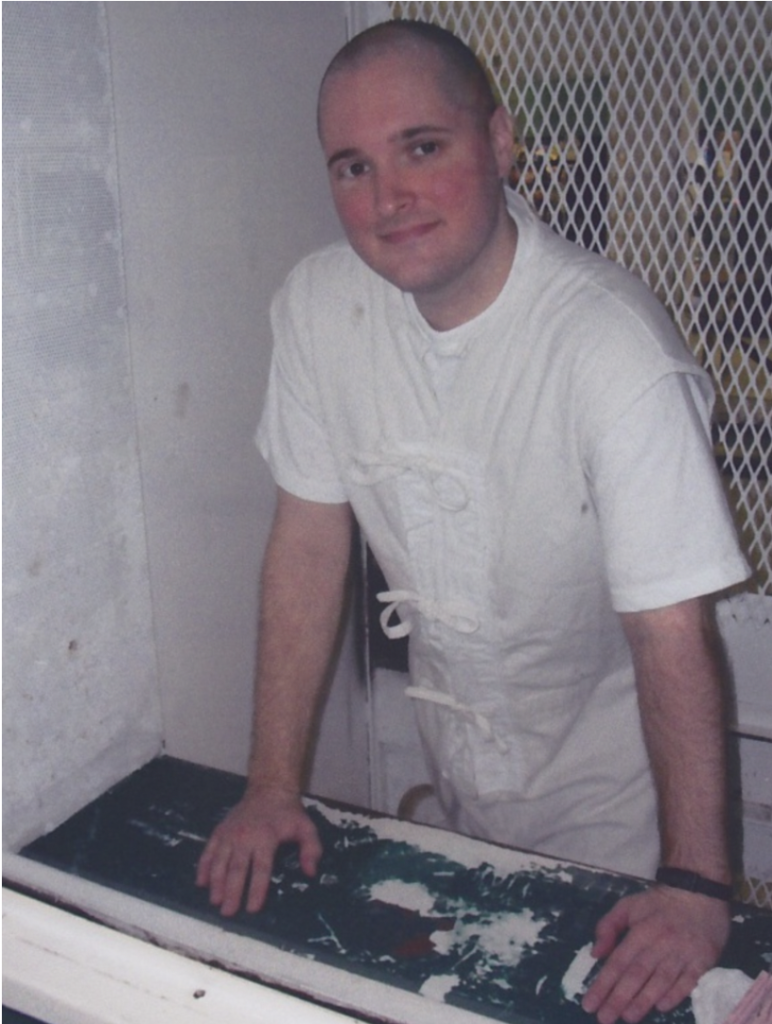

It was Valentine’s Day, and we were having trivia night, something that had become a regular event over the years. Solitary confinement can unravel a person’s mind quicker than freeworlders ever seem to understand. The sanity of many a man on Texas’ Death Row was preserved more than a decade in the past when we figured out how to create an intercom system. By using one half of a set of headphones as a microphone, a relatively simple hack of the radio board’s audio chip, and thousands of feet of vanishingly thin wire purloined from your average transformer strung from cell to cell in progressively clever ways, we’d found a means of creating community in a world calculated to foster the radically alienated. Some men played chess, others Dungeons and Dragons; some had Bible studies, nearly everyone engaged in that old weapon of norm enforcement and reality testing, gossip. Back in 2012, a friend of mine in the freeworld had purchased a Trivial Pursuit set and had started mailing me the cards, so by the time I got my execution date I had amassed around four hundred of them. For a while we played things pretty straight, Jeopardy! style, but, given the fact that everyone in my set had a rather large soft spot for pranks and general mischief, the Wheel of Misfortune came into existence to… ah… spice things up a bit.

On this particular evening, the Wheel had decreed that the final question fell on Rabbit’s shoulders. Rod seldom came in last place, but he’d had an off night; if the field lost, he would bear the punishment. Normally the person in first place had the honor of answering the final question, but I’d blatantly cheated and had given easier questions to Rabbit, forcing Judge into second place. (Cheating, I should note, is an honored and at times downright sacred aspect of most of the games convicts play. Whether this is due to some innate moral flaw in prisoners or simply a result of the lessons Mother Prison daily teaches us, I leave to the Reader.) This skullduggery had worked out well, until Rabbit had managed to pull an elephant out of his backside. If he’d missed it, Rod would have had to pretend he was riding an invisible horse every time he left the cell the following day, a la Monty Python, complete with little clop-clopping sounds. That was the plan, anyways. Now, I would have to speak with a Cockney accent for 24 hours.

Our friends were accustomed to our weirdnesses by this point. Any time one of us would show up in the dayroom wearing, say, a pair of boxer shorts wrapped around our heads, they would just nod and say: “The Wheel got you, huh?” All things considered, the accent thing was pretty tame by comparison to some of the punishments we’d devised over the years.

We were really just killing time, waiting for mail-call. My dad, stepmother, and uncle had driven to Austin the day before and met with the Chairman of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, in an attempt to have them vote in favor of a recommendation to Governor Greg Abbott for commutation of my death sentence. I had no doubt that they had sent me a JPAY email that afternoon, letting me know how things had gone, but I hadn’t received the printout yet. Under normal conditions, I was certain that I would have already had a visit with someone, but my first set of “all day” visits began that Friday, which counted for the only visits I was to be allowed that week. To say we were all waiting on pins and needles is something of an understatement: we all knew how important that meeting was to my survival.

Finally, sometime after 9pm, mail was delivered. I received the usual torrent of religious screeds, an obnoxious coterie of right-wingers gloating over my impending doom (apparently someone had been petitioning a gang of intellectually paraplegic digital storm troopers to send me postcards with “tick-tock” written on them in red, as I’d received more than six dozen of these over the past few months), a book, and – thankfully – an email from my dad.

“Bingo,” I called into the mic, scanning the text below. I began reading it out loud. “So, they met with Gutierrez, but none of the other members were there. That fits with our understanding that if more than one member is ever in the same place, the Open Records Act kicks in, which they never permit. Um… Gutierrez was cordial, my dad claims, but very non-communicative,” I said, frowning. “He never showed any emotion. He let my dad, stepmother, and uncle Keith say everything they wanted. There was an African American woman in the room as well, taking lots of notes. Keith Hampton said she was the Board’s General Counsel, and was probably the most important person in the room. Supposedly she drafts the brief that is going to be read by all of the other members. That’s it,” I concluded, seeing that the rest of the email had nothing to do with legal matters.

“Not much of a ‘hearing’,” Judge commented, the ironic air quotes obvious from his tone.

“I was hoping for… you know, lots of people. Cameras. For everything to be open,” Rabbit added.

“Yeah,” I sighed. “Me too. But this Board does nothing in the open, so that was probably an unreasonable expectation. In better news,” I shifted my tone as I looked over the gift receipt that had been inserted inside the book I’d received a few minutes earlier. “Someone sent me Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. The Amazon gift receipt says, and I quote: ‘Pushkin died at 38 too.’”

“Uh… that’s… nice?”

“I’m not actually sure if that was meant as a consolation or… I don’t know, some kind of jibe. Whatever: either way, I don’t have the time left in this life to read this. Who wants it?” I opened the book and began to read to myself at random:

“Whom to love, whom to believe in,

On whom alone shall we depend?

Who will fit their speech and on,

To our measure, in the end?

… never pursue a phantom,

Or waste your efforts on the air…”

“That’s not the major problem here,” Rod said, his voice serious.

“Oh?” I asked, closing the book with some regret.

“What I want to know is: where is the damn accent already?”

Everyone laughed; I groaned: the sound of the Wheel spinning at high efficiency. “This’s a steaming pile of bollocks, I says,” I remarked, trying to get my mind into the right frame. “Ima get right knackered of this, I tells ya.” It was going to be a long 24 hours.

The following day the state placed me on the “Form 4 Execution Watch” log, what in a prior version had been called the “Zero-four” log, the source of our label as “zeroes”. This meant that every thirty minutes, an officer walked up the stairs and stuck their face in my door, and proceeded to jot down detailed notes regarding my activities.

“You okay in there?” they would always say, or something to that effect.

“Sod off, yer dozy cow.”

I could hear Rod cackle from down the run each time I addressed them. “You shut yer poxy marf, or I’ll clock yer one, innit!” I shouted at him. By the middle of the afternoon of the 15th, I was starting to run out of Cockney insults.

I was also running out of time. A few minutes after 6pm, I recall thinking: this is my last Thursday night on Earth. Every friend of mine living out their last months in Deathwatch I’d ever been on the mics with told me that they’d engaged in this exact same macabre countdown: last visit with a cherished cousin, last outside recreation period, last episode of the Prison Show on KPFT. The mind just can’t help but to note these benchmarks. What surprised me was not how utterly ordinary I turned out to be in this respect, but rather how much genuine satisfaction I got out of realizing that I’d suffered through a whole litany of Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) lasts: last shakedown, last time I had to listen to an officer bitch about overtime or how much they hated working there, last time they served us Fuck Me, Not Again (Tamale Pie to you civvies) on the trays. It got to the point where I was noting such developments with joy. Compared to the Polunsky Unit, sometimes death seems like a summer spent on the Cote d’Azur.

The following day, 16 February, I had the first of my all day visits. I had been telling my friends and supporters for years that when this day finally arrived, I was reserving those last spots for my closest friends. This can sometimes cause quite a bit of drama, as everyone naturally wants to say goodbye in person, but I was very fortunate to have collected a solid, mature, intelligent crowd of friends over the years that understood my position intuitively. For that Friday, I was seeing my friend Dorothy from 8am to noon, then my dad and stepmother in the afternoon. I was expecting these to be difficult ordeals, but everyone involved was trying to make things easier for the person or persons on the other side of the glass. The predominant feeling of these conversations was love, a point for which I was immensely grateful.

If there was a single instance of stress, it came when my dad told me that they’d decided to skip the visits on Tuesday in order to be in Austin when the Board announced the results of the clemency vote. Attorney Keith Hampton had the idea of renting one of the media rooms at the Capitol; earlier in the day they would attempt to speak with the Governor, and then pack the room with representatives of media sources from across the globe. The thinking was twofold: first, if there were backchannel conversations happening between the Governor’s office and the Board, pressuring the former might give each of the Board members a little space to act the way they wanted to. Second, in the event of a Board denial, the press conference might give Abbott the political cover to grant a 30-day reprieve in order to better analyze our position and arguments. This last was clearly a desperate move: Texas Governors haven’t seemed to have any political problems with denying clemency, and if everything we’d tossed at him in my petition wasn’t convincing enough, I didn’t think a crowd of liberal supporters was going to matter.

My main problem with this plan was the one I could not state: that if the Board denied me on Tuesday, I was expecting to end my life that night, when the scrutiny on me would be considerably weaker than on the 21st or 22nd. This meant these Friday visits were probably my last with my dad, and I couldn’t even tell him, for fear of showing my cards to whomever was no doubt listening to our conversation.

In the end I didn’t try to send them any signals. If I were executed, what seemed most important was that my family had the ability to say that they had done everything possible, that there not be any lingering “what if we’d only…” moments. They felt they needed to be in Austin, so that’s where they’d be. I made sure our goodbyes were indelible though, in case that was their last memory of me.

My final weekend. My final run outside in the cold, with Rod. My final book: Douglas Hofstadter’s I am a Strange Loop, a wonderful little discourse on consciousness, which, unfortunately, is dominated in my current memories by his inclusion and discussion of Roald Dahl’s short story “Pig”, in which the protagonist visits a slaughterhouse and then subsequently has his throat slit on the production line. I guess Lexington’s plight felt just a little too close to my own for comfort. My final contact with the extremes of music: my last Metal Madness on Big Dog, in which they played Lacuna Coil’s cover of Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy the Silence,” followed by the Sunday Night Concert on NPR. The actual music wasn’t all that great – never been a huge fan of Schoenberg or that whole atonality thing – but given that most of the stations we can pick up at Polunsky play trash, it felt like an appropriate way to end my relationship with music. The person I was at 23 never would have listened to classical, would not have known to have longed to hear Osvaldo Golijov’s “Azul” or Arvo Pärt’s “Fratres”, so in some way I was able to feel the changes I’d gone through over the years very viscerally.

That Monday, President’s Day, I completed my final letters. I didn’t want to spend what might be my final night stressing over correspondence, so I resolved that if I hadn’t finished the letters by 11pm on Monday night, they weren’t getting completed. I wanted my end to be relatively tidy, and in this I had at least a modicum of success. I spent that last night of leisure reminiscing with my friends. They couldn’t help me with the death part, but they made the dying vastly easier to take.

Tuesday’s visits were originally going to be divided between my parents and my close friend Dina Milito, but with my dad’s change in plans and trip to Austin, I would be seeing only Dina. She had pretty much become family over the decade that I had known her, so this seemed fitting. Most of the condemned lose large portions of their family connections during the long wait for death. In my case, that severance was immediate and easily explicable: although everyone was opposed to my execution, very few of my extended family wanted to have anything to do with me after my arrest. Into this vacuum of important relationships occasionally step random people from the freeworld. Such penpals/activists/whatever often come in for derision by some who cannot understand why anyone would write to a criminal, but in my experience the reasons are seldom tawdry or romantic. Some sense a deliberate hollowness to the media portrayals of the crimes that sent us to prison, and find they cannot put their minds to rest until they have a better understanding of what actually took place. Some comprehend the deterministic power of broken homes and underfunded schools and seek to in some way counterbalance a court system that hews to a more libertarian view of free will. Most, I have found, are simply wired in such a way that when they observe chaos, pain, and ruin, they immediately respond with desire to heal. There have always been such people; the world hasn’t been reduced to ashes because of them.

If you had told me after I’d received Dina’s first letter in 2008 that she would become my best friend, I probably wouldn’t have believed you. Her initial questions were sharp, if not outright cutting. She wasn’t going for my evasions or defense strategies, especially the ones I wasn’t completely cognizant of. She was a lighthouse through some dark years and a lot of self-discovery. I learned over time that she herself had been the victim of a violent crime, which made her attempts to understand my actions more explicable. It also made her empathy all the more confusing sometimes. It was of course wonderful to have someone interesting to write to who was intelligent and interested in literature. I often felt unworthy of this boon, and this mixture of joy and shame seems to be one of the hallmarks of most of my post-arrest friendships. I never lost sight of how fortunate I was to meet her or any of the other people that have come my way over the years. I didn’t deserve this grace and struggle to explain it.

Beyond being my friend, Dina eventually became the Executive Director of Minutes Before Six, so she was technically also my boss. She has the ability to be both encouraging and critical, understanding while firm on matters of boundaries and deadlines. This combination of traits was particularly useful after I received my execution date, because she organized the massive letter-writing campaign that was critical to my clemency efforts. She kept the well-meaning on leash and muzzled some of the internet activists whose execution playbook seemed to have been meticulously calibrated to be both completely worthless as well as maximally annoying to the very public officials I needed to win over. Having her handle this aspect of my clemency bid gave my attorneys one more tool that they didn’t have to craft on their own. That we had tens of thousands of letters, emails, and phone calls flood the TDCJ during my months on Deathwatch was largely a result of her efforts.

Given my father’s mission in Austin, it would fall on Dina to learn how the Board had voted and relay this information to me. The State was supposed to make public their decision at 1pm, so the plan was for Dina to go out to her car at 12:45pm and await the news. If things went poorly, I would have a little more than 50 hours left to live.

That was a hell of a wait. 1 o’clock came and went, then 1:15, 1:25. As reality dragged its swollen carcass along, I grew increasingly pessimistic. Dina is a tough girl, so I simply couldn’t believe that if the news was bad, she would delay notification so that she could have a good cry in private, but I couldn’t imagine what was holding her up. I tried meditating, and failed. I tried again, failed harder. I’d have paced if there’d been room, but the cage they reserve for zeroes on their last visits is set apart from everyone else and is incredibly tiny.

Finally, at nearly 1:45, I saw Dina re-enter the visitation room. Citizens have to check in with the officer in charge of the visitation room, which meant she had to pass by my cage and re-register her presence near the vending machines. The plan was for her to give me some kind of signal, but the look she flashed me was… haunted. She motioned for me to hold on and then disappeared behind the partition that bisected the visitation room. I didn’t know how to interpret her visage other than failure. My first thought was: well, I guess that’s that.

A few seconds later, Dina came flying around the barrier and dashed into the small room adjoined to my cage. She grabbed the phone and nearly shouted: “Seven to zero for clemency!”

I was stunned. We’d never even considered such a result, mainly because it had never happened before. As in, not once, in state history. I think I said something like, “Well, I’ll be damned” before doubt started infiltrating the nascent possibilities. “Wait, are you sure it wasn’t 7-0 against?”

“It was an unanimous vote for clemency,” she repeated, her voice curiously flat. I gave her a long look. I could almost see waves of stress dopplering off her, several emotions clearly competing for prominence on her face. Later I would reflect that of all of the emotions that I felt or that were expressed by my friends and family, joy was never present, not at first. A strange kind of relief, maybe, but one that strongly suspected that the next flight of planes and their bombs was going to be more accurate than the last. I’d witnessed this in other men who had received positive news about their cases. There’s something about the Death Row experience that leaves a person mentally sandblasted to the extent that the emotional crests and troughs of life get lopped off, leaving only the grey middle. A less experienced person would have thought I was in shock, but I knew better: I’d been like this for years. It’s who prison has turned me into.

Dina and I spent the rest of our visit deconstructing the vote, allowing some percentage of the stress to bleed off. Around 3pm Attorney Salima Pirmohamed showed up, so we spoke for about half an hour. She was equally stunned, and reported that Keith Hampton believed that there was no way Governor Abbott could execute me now. “He said to get ready for population,” Salima added just before she left.

I returned to the section to see Rod smiling at his door.

“You heard?”

“Dude, it’s all over the news. Your prosecutor nearly had an aneurism on CBS earlier.”

It took me a few hours before it really started to sink in: I might not actually be dead on the night of the 22nd. I’d seen how hope could destroy a man’s self-control back here, so I wasn’t willing to really open myself up to the possibilities, but still: seven votes for clemency, none against. My theory about clemency had worked out better than any of us had expected. I went to sleep that night with a sense of calmness that I hadn’t experienced in months. Whatever happened, I’d showed that the Board was open to being convinced our lives had merit.

The next day I was scheduled to see my friend Wayne from 8am to 11am, my dad from 11am to 2pm, and then Dina again from 2pm to 5pm. No word had come down from the Governor by the time my father arrived; I could tell this bothered him, like he had expected Abbott to sign the paperwork that morning, and end his misery. During our hours together, he recounted the events of the day before in Austin.

The media room they rented in the Capitol complex was close to full with reporters, camera crews, and various officials; the Democratic state Senator from the Austin area was there to lend her support, as were a few obvious monitors from the executive wing of the building. Keith Hampton made some opening remarks around 12:50pm, followed by my dad and my uncle. The 1 o’clock hour came and went. At twenty past, Hampton called the offices of the Board to find out if there had been a decision, and was told that the fax machine was tied up and none of the members had been able to get their votes through. There was a low gasp that echoed out from the crowd of media representatives once this was announced.

“Fax machine? They are using a fax machine?” my dad later wrote, in his post-commutation debrief. “This is 2018, and the State of Texas is still using a fax machine. Incredible. But I guess consistent with everything else about the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.” (And people wonder where I got my smart mouth…)

Our contact within the clemency division offices would later tell us that they’d been inundated with letters, emails, and faxes all morning. When Keith asked if this meant hundreds of such communiqués, the man smiled and said: “Oh no, much more than that.” “Thousands!” Keith gasped. “Oh no,” the man said, turning to leave. “Much more than that. Everyone in the office was terribly annoyed.”

Another fifteen minutes would pass before Hampton received an email. He looked down at his phone, then moved to the microphone. “The vote is unanimous… for commutation!” The whole room erupted in cheers. My dad told me the next day that Keith’s pause was so long that he actually had time to think: “You mean we didn’t even get one vote?” I was able to hear this moment on the radio, when it was replayed on the news later that night. I could hear my stepmother sobbing after the vote was announced.

Immediately after the press conference ended, Kent, Tanya, Keith Hampton, and a bunch of reporters went to the Governor’s general counsel’s office, and asked for a few minutes with Abbott. They waited, and waited, and waited some more. Finally, the receptionist got a call from upstairs, and was told to write down a number for Kent to call; this was jotted down on a sticky note and handed to my dad, after which everyone was basically told to leave. (In a wonderful touch of irony, the sticky note was produced by the State Employees Charitable Campaign, whose motto, apparently, is “Together We Care.”) When Keith called the number, it went straight to voicemail, that time and every time thereafter. The entire thing was a charade designed to get them out of the lobby. Abbott never did communicate with anyone from our side, though we later learned he was in constant communication with the Assistant DA that tried my case, Fred Felcman, and the lead investigator. Indeed, he met with them twice on the 22nd, once at 9am and again at 12:30pm.

I don’t know what was said between these parties in the days leading up to the execution, but I do know at least one thing that wasn’t discussed.

Prosecutors in Texas are beasts of habit. Certain tactics are almost guaranteed to produce death sentences, so they all engage in them. Clemency is no different from a trial or an appeal: in pretty much every case, the same conservative, vengeance-oriented arguments are going to be sent to the Governor. In my case, however, at least some of these didn’t apply. I wasn’t a career criminal, so Fort Bend couldn’t point to a vast arrest record as a guarantee of future conduct. My disciplinary record in prison was clean, so this precluded the “see, he’s even dangerous in prison” justification that is an old classic in these filings. We decided early on that the most likely rationalization Fort Bend would offer for my death dealt with the type of life sentence that corresponded to the year I committed my crime. In 2003, a capital life sentence amounted to forty years before a prisoner became eligible for parole. We figured that Felcman would lead with some sort of “if you commute this sentence, Governor, a monster will walk free one day” argument. So we decided to take this away from them.

On 5 February, days after the supposed deadline for filing any relevant paperwork, we submitted a contract we’d drawn up between me and the State of Texas Parole Board, along with another large stack of support letters. The clerks at the clemency office accepted this, because letters are allowed to be submitted late, since they are considered time-sensitive. The contract stated that if the Board recommended and the Governor granted clemency, I would voluntarily waive my parole options once I became eligible. I had – and still have – no idea whether such a contract would be legally valid, but it seemed a good way to take Fort Bend’s biggest weapon out of their hands. If it bought us a few weeks of the prosecutor arguing over a point they’d already lost, it was a huge advantage to us.

Fort Bend ended up acting in exactly the manner predicted. They pounded the airwaves, broadcasting the threat to public safety that would develop once I became eligible for parole. What is remarkable – and I cannot stress just how amazing and atypical this is – nobody in the clemency division ever told Felcman that he had already been outmaneuvered. As late as Wednesday night, 21 February, the day before my execution, county officials were still using this very argument. Even though they were not told of the parole waiver, we believe that Felcman had started to pick up on some sort of signal from the state that his primary argument was worthless, because he also started floating the claim that my mother’s family was pleased about my impending death. To the best of our knowledge, this was a lie. My maternal uncle testified during my trial that the entire Bartlett family was opposed to the state seeking death, and we’ve had no indication that anyone ever changed their mind during my years on the Row. That my prosecutor failed to ever mention specific names to back up this claim is telling, and we came to know that no one in the clemency office gave this much credit.

My final night on the Row was as liminal a time as I have ever known: everything felt balanced on an atom’s edge, neither in nor out, safe nor endangered. With no news reports detailing Abbott’s decision, I had to believe he hadn’t made one yet. My own strong desire to end my life on my terms was now warring with the possibility that positive news could still come down the next day – although this seemed less likely to me as the hours passed by. In the end, the sad, Shakespearean death of Ohio inmate Billy Slagle convinced me to finally dispense with the suicide option.

Slagle hung himself on Sunday, 4 August 2013, three days before his scheduled execution. No one in the prison had bothered to tell him that two days before, the lead prosecutor in his case delivered information that almost certainly would have granted him a new trial. In the prison world, to “pull a Slagle” became a notorious term for making an important decision without complete information. As much as I hated the idea of having to take the trip to Huntsville and being placed on a gurney, the idea of future convicts telling one another that they’d “pulled a Whitaker” was worse. I spent my final night talking with my friends, who were unanimous in their belief that things were going to go well the following day. I never got to tell them how much that mattered. It would have been a miserable night without them.

Not surprisingly, the theme of the conversation turned to the afterlife, a subject I usually excuse myself from. This time, however, I was not permitted to bow out gracefully. Rod, only five weeks out from his own date, needed the exchange, so I felt I had to listen more attentively than normal. Judge was a fellow Catholic, so they did most of the talking. Rabbit was, I guess, a Unitarian of some sort – all paths lead to God, etc. Really he was a sort of spiritual bricoleur, having cobbled together a religious order from doctrines, moral codes, symbols, and theologies that was capable of surviving the pressures of the Row. I was the odd man out, a scientific materialist that believed when the brain died, identity died, full stop.

“I don’t see how you can live without that kind of hope,” Rod said at one point.

“Better a painful truth than a comfortable delusion. You are like Job: ‘though he slay me, yet will I trust in him.’ Doesn’t that seem weird to you? To trust someone that has the power to help you out but chooses not to?”

“But that’s pretty much the heart of spirituality to me,” he admitted quietly. “He wants a genuine relationship with you, so you have to take that first step of faith.”

“I guess I just can’t understand that anymore. I did when I was younger. If you have the power to help those you love, you will do so. God could have saved any of the men killed here but he didn’t. All of that desperate clamoring for some sign of a responsive superThou, and then nothing. The invisible and the non-existent sure look alike from where I’m standing.”

“But we have faith that it wasn’t nothing, just something that isn’t visible from where you are standing. Your view isn’t very good from that close to the dirt.”

I sighed. On this one point, we were speaking across the gap separating two worlds, and no such communication survives the vacuum intact. “For me, true spirituality is when you know nothing matters but you care anyway.” I paused, thinking. “I love you, you nutty zealot.”

“I love you too, you godless heathen.”

“Technically I’m an apost–”

“You’re ruining the moment.”

“Ah… sorry? Kumbaya?” Rabbit immediately began singing.

Rod sighed. “I take it back. That is ruining the moment.”

I woke up a little after four am. I’d already given away nearly all of the property I’d collected over eleven years; what was left were items that would hold some sentimental value to my family and friends. I spent about an hour cleaning the cell thoroughly. Someone else was going to be placed in 10-Cell before long, and on that awful day, the worst they’d experienced in their lives, most likely, the last thing they needed was a dirty cell. At 5:30 Officer K- came around setting up recreation.

“It’s your big day,” he said to me, either trying to make light of the situation or being an unmitigated prick – I never determined which, as K- had the ability, like most humans, of being both decent and wretched in an alarmingly tight sequence. Either way, if this was my last day on this huge-tiny-ugly-beautiful rock, I wanted it to be nothing but disciplined, so I ignored him and simply asked for my shower.

All of the guys were on the mics once I returned to my cell. Everyone was still optimistic, but if the best possible outcome came to pass, we were all aware this was likely to be the last time we ever got to speak to one another. Even if my sentence was commuted, I was about to lose some of the closest friends I’d ever known – the kinds of bonds that can only be forged in a crucible. If I survived the day, I knew I would miss them. I just didn’t know how prevalent that feeling would become.

At 7:45 I began steeling myself for the trip to visitation. I’d seen them treat men with respect (Rayford), and I’d seen them treat men horribly (T-Bone and Batman), and I had no idea how the Major viewed me. Everything felt flat and I was happy for this, though on some level I was cognizant that I had done real psychic damage to myself getting to the point where I didn’t feel fear; this was another point that I thought I understood at the time, only to realize as the months passed that the damage went much deeper than I knew. Fortunately, when they showed up, the escort team consisted only of two officers; apparently the Major didn’t hate my guts after all. I got to pause on the way off the pod and listen to everyone wishing me well. “Have fun in population!” someone screamed just as the door slammed, and I wanted to smile but I couldn’t.

I was scheduled to see Dina from 8 to 10, and then my dad and stepmother from 10 to 12. I had hoped that Dina would show up with news that the Governor had commuted, but as of 7:45 when she had to leave her cellular phone in the car to enter the prison, there had been no news. I felt this was bad news. Abbott knew what my father was going through, but still he waited. That seemed cruel, even for him. I couldn’t wrap my mind around the idea that he was still undecided. Dina seemed to think that whatever this delay was, it was at its heart political: the Governor was still reviewing the pulse of the media, the people. I reluctantly agreed, not really having a better theory. We said our goodbyes and then Dina left to pull Rod out for a visit.

Over the course of the next half hour, I would see quite a few of my friends escorted into booths. That pleased me in a dull, truncated way, because they were there to send a message to the warden: the state was going to treat me right, or there would be trouble. I’d set up such visits in the past when one of my friends had a date, and now it was my turn.

The last visits with my dad and stepmother were tough. Everyone had expected word from Austin by this point, and it was starting to dawn on them that the execution was growing more likely by the moment. In my father’s words:

“We started our visit in a positive, but somewhat fragile state of mind. I mean, surely he would agree to follow the unanimous decision by his parole board! Wouldn’t he? How could he ignore a vote like that from all seven members (people he had appointed) – everyone a solid death penalty advocate? These people were former district attorneys, policemen, County Sheriffs, and TDCJ career officials, and yet they had voted unanimously for commutation? How could he ignore that?”

My stepmother’s account focuses less on the broader political issue and more on the human:

“Last goodbyes are painful, but also natural when someone is passing from old age. But last goodbyes when someone is going to be executed take on a whole different dimension. There is no soft touching of the hand or goodbye hug. There is palpable pent-up tension because everyone is directing their emotional energy toward trying to remain stoic and brave and not upset the other while trying to hold on to some thread of optimism in the face of the clock ticking down. Some of it was surreal. I honestly never thought we would get to That Day. The board had historically and unanimously recommended clemency. How could the Governor disrespect the recommendation of the very professionals he had appointed to do the due diligence? The silence was deafening. And how do you say goodbye to your son for whom you have fought much of your life to save by putting your hand on a piece of glass and speaking through a muffled, scratchy phone? Kent and I were weary and heartbroken as we turned to walk out of Polunsky for the last time.”

My dad again:

“Over the course of Thomas’ incarceration, it was abundantly clear that the TDCJ cared little for any inmate’s family. They have shown this in countless ways, large and small, for years. But one of the most offensive things they have ever done happened at the end of that last visit. It would turn out to be just one of three that day.

As our visitation time was nearing the end, I noticed that a uniformed woman I had never seen before had come into the visitation area and was obviously waiting for us to finish. When noon arrived, she came to say that the visitation was over. This is nothing new, because that’s how every visit ends. Tanya and I pressed our hands to the glass, said we loved Thomas, and turned to go. The woman fell into place right behind us and followed us out of the visitation area, through the two sliding electric doors, and into the long hallway leading to the building’s exit. I thought she was just walking out of the visitation area with us, but then I realized that she was sticking to us like glue. We sped up and she sped up. My emotions erupted. I swung around and said “Why are you following us? We know the way out!” But she stayed with us. “You mean you are actually ESCORTING us out of the building?”

We hit the door and began the 100 yard walk to the exterior fence. She was still right with us. It was humiliating and felt vindictive and creepy and mean. It actually made us feel dirty. Tanya later said she felt like she needed to take a shower. Still, the lady stayed with us all the way through the fence and into the parking lot. She kept following us, staying a step and a half behind us. I was furious, and am sorry to say that I lost my temper. Of all the nasty things TDCJ had done over the years, this was the worst.

Of course, it really wasn’t, but it felt like it at the time. Escorting us off the property? As if we were vermin who needed to be watched? She replied that “it wasn’t personal.” I lost it and shouted at the top of my lungs “like hell it isn’t! It is the most personal thing you do!” But at least I kept walking; the guards in the towers had obviously heard me. She stood in the parking lot until we drove our car off the prison property. I felt helpless and demeaned. It was in that state of mind that we headed to Huntsville to witness my son’s execution. The Governor was still silent and the execution was now less than 6 hours away.”

It broke my heart to read those words the first time, and it still bothers me today. Converting humans into vermin is what they do here, and while I may deserve such treatment, they did not. I’m glad they were not there to witness what came next, after they were herded out.

First came the Extraction Team, complete with more than a dozen ranking officers, a pair of handheld cameras, and eight or nine officials in suits. I was led from the visitation booth directly into the restroom, where I was stripped down and my clothes ransacked. From there I was placed in restraints and led out the back door of the visitation building. On the way, I was able to look through the booths and see my friends Dina and Rod for what I expected to be the last time: they were both staring at me, their hands on their hearts. It made me smile inside, though I couldn’t let this reach my face. I was taken back to 12-Building.

Our group was met by even more people in freeworld clothes. I honestly have no idea who they were, or why the presence of three dozen of them was necessary. I was led to the observation cage in front of C-Pod. Once inside, eight officials surrounded the cage, two on each side. I was stripped again, and handed a completely different jumpsuit and a pair of cloth sandals that must have been about size 17, they were so huge. Each time I handed them an item, an observer would note this, and then this would be recorded for the camera:

“Offender has relinquished personal shoe, left, size 10.5.”

“Offender has provided his left shoe.”

Once naked, I had to spin around for the crowd to see, and then prove that I had no contraband hidden anywhere. Only then was I allowed to dress. Once handcuffs were in place, I was led to the BOSS chair, which is basically a metal detector for one’s backside. I always set the chair off – it’s the bullet fragments still in my arm, plus plates, screws, and god-know-what-else the quacks at UTMB left in there during my pair of surgeries ten years ago. Everyone got very tense as the chair started buzzing angrily. The head warden ooomphed his way over and ran a handheld device over the obvious scar that runs from my left elbow to my shoulder, and then spoke into one of the hovering cameras: “Offender has metal implants in his arm.” Once this cover-your-assery was complete, I was placed in leg shackles, belt, and then had “the box” placed over my cuffs. This is a device that locks your arms into position, one above the other, as if you were holding an invisible box. Aside from making one extremely uncomfortable, I’ve never been able to divine the purpose of this contraption, unless it’s a sort of message regarding our relative power against the state apparatus: we are confetti in the face of the hurricane-power of the TDCJ.

I was handed off to the transport team, which consisted of seven men spread across two vehicles, a black SUV and a white van, imaginatively labelled “the death van”. This latter is a GMC Econoline with a steel cage built inside of it. The driver was armed with a pistol, the man in the passenger seat with an assault rifle. There was also a bench in the back, outside of the cage, where a third officer sat with a pistol and a shotgun. As I was loaded into the cage and placed on the slick metal bench, I was told by the guy with the rifle that if I had any friends waiting for me on the route, the man with the shotgun was going to “paint” the inside of the van with my “rotten guts”. As he said this he put his finger under his left eye and pulled his eyelid down: I’m looking at you.

I shrugged. “Something to look forward to.” I don’t really know what I was trying to do, make him feel silly or paranoid or what. I really couldn’t tell you what I was feeling because I was completely numb. About the only coherent thought that I can recall having at the time was that I had started to regret not killing myself the night before. I was having a hard time believing anything positive was going to come from Abbott by this point.

The van had no windows on its sides, but I could look through the cage out of the front or the back. I noticed as we pulled out of the unit that we’d picked up two lead vehicles and two more chase ones; I would eventually notice a few more at traffic lights, stopping vehicles to allow our passage. Apparently the entire group had decided to attempt to break the land speed record for transit between Livingston and Huntsville, because we damn near flew. There was no traction on the metal bench where I was seated, so I began the trip by sliding all over the place until I figured out how to lock myself in place by wedging my knee up against one of the cage’s interior partitions. After that, my main focus was on controlling my nausea.

It was a cold, grey, rainy day; I recall thinking that at least the weather felt appropriate: if one has to be murdered, having this done on a sunny day with birds chirping seems a kind of betrayal by nature. The trees of the East Texas Great Piney Woods pierced the undersides of the clouds like little daggers, and a steady if slow rain blanketed the entire drive west. Since we travelled at a significant fraction of the speed of sound, I noted that the wet roads at least offered the possibility that we could all die together in a fiery automobile accident. I wish I was kidding about this, but the guards in front talked about hunting the entire trip, something about a “$10,000 a gun” trip to Africa to kill something presumably exotic. Sometimes the clichés make you yearn for large extinction events.

We pulled into the Walls Unit in Huntsville at around 1:30pm. A steel gate in the rear of the prison slowly cranked open, and the van pulled into a sally port. As we waited for the gate to close behind us I could see a pair of officers shouting at a group of inmates loitering around an open door. They looked from the COs to the van and then disappeared inside. Another gate opened and we proceeded through what looked like the backside of an industrial park: concrete loading docks and ramps, trucks half-emptied of goods. The entire place was abandoned, though it looked like it had been bustling only moments before our arrival. We turned three times (I think) before pulling up to a pair of narrow gates, each one made of chain-link and topped with razor-wire frosting.

On the other side of the second gate sat a squat building made of red brick. I don’t know when this version of the death house was constructed, but it was clearly of a later vintage than the rest of the prison it was attached to; my guess, based on the style of the architecture, would peg it some time in the late 50s or early 60s. Standing in and around a thick metal door were more guards than I could count, all of them wearing various pieces of metal on their collars: ranking officers, one and all. Apparently execution duty was not for mere COs. I didn’t see any suits, and wondered where the actual decision-makers were stationed, and if any of them were sitting off to the side, having the sorts of internal doubts that permeated the mind of the narrator in Ivan Turgenev’s “The Execution of Tropmann”. Somehow, I kind of doubted it. I also wondered how many men had walked through these doors thinking these sorts of thoughts, if I was the only one using literature as my shield against a dark star too blinding to stare directly into. I doubted that, too, and wondered how many of the supporters of all this madness would continue to do so if they had access to the collected thoughts of the condemned in their final hours.

I was led into a narrow hallway of perhaps fifteen feet by sixty or seventy. To my right were the death cells, to my left the exterior wall. I wasn’t able to count the exact number of cells, but I think it was ten. The cells were old, clearly predating the mass incarceration era, with simple steel bars extending the full front of each cell. Maximum security inmates haven’t been allowed in such enclosures for decades. I was led to a table where my fingerprints were taken with actual ink – no fancy scanning equipment in the death house. I’m not actually sure what this was for, since my identity had been confirmed several thousand times since my arrest in 2005. I suspect they simply keep a record of prints for the ghastly little prison museum the TDCJ maintains in Huntsville, where visitors can view glass cabinets packed with shanks and touch one of the chairs used in electrocutions in the past. Or maybe it was simply policy, and policy can never be deviated from.

I was placed in the third cell towards the front of the hall. Roughly twenty feet to my left was a steel door with a small, rectangular security window. The little steel door that covered this was swung open, and I could see tiles colored the strangest, ghostliest shade of green. I’d seen photographs of the death chamber before in magazines and newspapers, but they never did justice to just how strange this particular tint really is. In roughly four hours, assuming the Governor did not commute, I’d be walking through that door.

The most remarkable thing about the cell they’d placed me in was that it actually had a pillow. There haven’t been pillows in the TDCJ for decades; like everyone else in the system, I’d been using a stack of shirts, boxers, and shorts for ages. I sat on the bed and put my hand on the pillow, just concentrating on its otherworldly softness. I then tracked my eyes across every square inch of the cell, trying to record everything. We only get to die once, and I wanted to be completely present and aware of all of it. I suppose these are the silly things one thinks about when one is completely out of choices.

My meditations were interrupted by a man in a black suit. He called me “Bart,” a shortening of my middle name that no one calls me but the media and my prosecutor. He introduced himself as a TDCJ chaplain, and tried to make small talk. “Lived in Texas your whole life?” he asked.

“Not yet,” I responded, wishing he would go away. Miraculously, he got the message, although I don’t think he really comprehended all of the implications of my response.

At 2pm I was allowed to use the phone. This was the first time this had been allowed since my time in the county jail, as prisoners in admin-seg wings in Texas are not allowed to access the telecom system used by normal prisoners. There was one caveat to this arrangement: the only number I could call without special permission was that corresponding to the Hospitality House, a facility just down the street from the Walls Unit. The family and friends of the condemned usually gather there after the final visits are concluded at the Polunsky Unit. I wasn’t allowed to touch the base of the phone; this was placed on a stool about a foot outside of my reach, and the chaplain had to ask someone in another office to dial an outside number. The whole time, a pair of officers stood against the wall, staring at me gloomily and listening to everything I said. They didn’t seem to like the description I gave to my stepmother of what the place looked like.

“You ain’t talkin’ to no media, is you?” the one on the left, whom I’d already christened as Sturm, interjected at one point.

“Cuz you cain’t talk to no media,” Drang echoed.

I nodded my head in the negative, but I’m not entirely sure they believed me.

A large table sat against the opposite wall from my cell. On it sat two large platters of pastries and an urn of water and another of coffee. When asked if I wanted something, I replied that I wasn’t hungry. This extended to my last meal. Once upon a time, inmates were allowed to order from a fairly extensive list of items: fried chicken, fresh fruit, ice cream. This practice was ended with the execution of Russell Brewer, who ordered a feast and was then too nervous to eat it. Senator John Whitmore misinterpreted this as an intentional last act of malice and ended final meal requests. Since then, the condemned eat whatever is on the menu for dinner at the Walls. I’m told that the kitchen captain attempts to make something decent on execution days as a result. I can’t really say, because I did not eat my last meal. Apparently one of the local news stations showed a clip of a pair of hands cutting up a pair of enchiladas on a prison tray, implying that the hands belonged to me. I have no idea why this was done. Camera crews are definitely not allowed in the Death House during an execution.

At 3:30pm, my dad, stepmother, Wayne, and Dina were given execution orientation by several TDCJ chaplains. The list of people allowed to witness the execution was something of an unsettled issue right up to this point. I was firmly against anyone attending. I’ve known people that had attended this festival of vengeance before, and it scarred them. I didn’t want this for my family or friends. I also didn’t want this to be their last memory of me: tied down, surrounded by thugs in uniforms. The problem was that many of my loved ones claimed that they needed to attend. Not wanted, needed. In the months leading up to my execution, this was arguably one of my greatest sources of stress, this tension between what we all thought was right. The final decision had to be made on the day I visited with the head warden two weeks prior to my date. If someone’s name wasn’t on that paperwork they weren’t getting in, at least not in the booth reserved for my family and friends.

In the end, I decided to put the names of people I could trust not to enter the Walls if I still felt strongly about this issue on the 22nd. The condemned are allowed five witnesses; my supporters would be my dad, stepmother, Dina and Wayne. Several of my other friends wanted to be there, but were so adamant about their presence that they would go in whether or not I wanted them there, so they were left off of the list. The orientation these four attended began about 3:30pm. I’ve been told by other witnesses that the real purpose of this class is for the chaplains to get a better idea of which of the witnesses might be a security problem inside the prison. This syncs up with what my dad wrote, after the fact:

“Several TDCJ Chaplains came over to give us an ‘orientation’ of what to expect – all very surreal. There wasn’t much comforting going on. They led us into a tiny bedroom and we all crowded in: Tanya and I, two friends, and the chaplains. Instead of explaining things in a way that acknowledged what was about to happen to our loved one, it was a checklist of things we couldn’t do. Then there was a discussion of what we would see and how we were allowed to respond to what was happening. Lots of do’s and don’ts. All that was important, of course, but it was so cold and matter of fact; it was like we were being told the requirements and parameters for a tour of NASA or something, and not the ending of a loved one’s life. They seemed oblivious to what they were doing or our reactions; their visit would have been more appropriate for the family of a victim who was primed and ready to see some state-approved vengeance. They finally finished and left, acting as if they thought they had done a good job, instead of making us even more shell-shocked than we were.”

My stepmother’s account reads similarly:

“The room was hot and stuffy. Two prison chaplains came in and began to explain the execution process –where to stand, don’t approach the glass, don’t speak, how the inmate would come in strapped down and ready, how he would be able to say last words but us not respond, the process of beginning the lethal injection, what to do if we felt faint, where reporters would stand, the 5-minute wait until the doctor comes in for the official death pronouncement. Kent and I began to weep.”

By the time everyone returned from the orientation and to the phone, it was past 4pm. My reservoir of hope was empty. It had been running on fumes all day and had finally sputtered out completely. It just didn’t seem likely to me that Abbott would have planned to commute at the last minute. He’d been taking a beating in the press for days now; why go through all of that abuse only to cave at the last minute? It seemed to me he’d always known he was going to ignore his own Board, and just had to get through two days of bad press to get through everything. As the hours passed, more and more letters, emails, and faxes poured in from across the globe. We were able to read about some of these in real-time, some we only learned about in the following weeks. They were from ordinary people, bishops, priests, military generals, politicians – even the Pope got involved late in the afternoon. I didn’t hear about this until much later, but I know that Rod had to have had the widest, goofiest grin on his face when he heard the news. None of this seemed to sway Abbott. He didn’t seem capable of being swayed.

All day, the lawyers had been in conversation. As the afternoon progressed, they had a difficult decision to make. It was becoming increasingly clear that the Supreme Court and the Governor’s office were waiting on the other to act: neither wanted to be seen as responsible for precluding my execution. Attorney David Dow put it best, in an email from 3:24pm: “it is beyond fucked up these institutions play chicken with each other.” Given the unanimous decision from the parole board as well as the positive tone of the news coverage, the decision was made at 4pm to formally withdraw my petition in the Supreme Court, essentially abandoning for all time my legal options. Keith Hampton raced to the Capitol with a letter for the Governor’s Office of General Counsel. According to Keith, the receptionists treated him “like a man who had reserved a table at a restaurant – smiling, attentive, and oddly perky.” At 4:14pm Attorney James Rytting emailed him: “That sounds really bad!” Keith did not disagree.

Eventually the secretary for the general counsel came out. Keith informed her in clear terms that there were no more judicial proceedings, that it was entirely up to Governor Abbott now. We’d removed the Supreme Court from the game of hot-potato: only he bore the responsibility now for my life or death.

At 4:30pm we finally had to make a final decision on who was attending the execution, as nearly everyone now realized it was likely to happen. I caved, agreeing to allow Dina, Wayne, and Tanya to attend. My dad, fortunately, agreed not to. In his words:

“For two years people who had witnessed an execution had tried to talk me out of going; they said that the sight was not what I would want as the last remembrance of my son. Of all those trying to stop me, the strongest and most persistent was Tanya: she wanted to go in my place. All along I had said that I was going to be there, so that he would know that I loved him and that someone acknowledged that he existed and was a fellow human being. But as they had all pointed out, I had spent the last 15 years proving daily that I loved him, so when it came to it, I finally relented to Tanya’s and Thomas’ wishes. Dina, another friend, and Thomas’s close friend Wayne would represent me. I was confident that Thomas knew how much Tanya loved him and knew that Tanya would be a fierce advocate if anything happened during the process.”

At 5:00pm, I said my goodbyes. The phone was taken away. My three witnesses went to the Walls, where protestors and media members were gathering behind police tape. The “pro” side of the street was empty. After being thoroughly screened and patted down, they were taken to the guards’ breakroom, which acted as a waiting room on execution days. While they waited, guards kept coming to purchase items from the vending machines, and visit with their friends about what they were going to do on the weekend.

Less than a hundred feet away, I sat in my cell. The chaplain had pulled up a stool and explained to me what was about to happen. He seemed to have done this often, because it was all very humdrum, his spiel. At one point he nodded to the back of my cell towards a grate. Through this, I could see pipes and electrical wiring, and what looked like a narrow concrete hallway. The chaplain told me that if I saw people moving around back there, it meant the execution was going to happen, because that passage led to the chamber where the drugs were pumped into an IV system that ran through the wall and into the death chamber. I was trying very hard to remain calm, but the way he mentioned this, his tone of normalcy and even expectation, caused me to open my eyes and turn towards him. It hit me instantly that this man wasn’t just doing a job; he believed in my execution.

Looking into the man’s eyes, I thought of Gauguin’s recollection of the “murderous expression on the face of the priest” when he witnessed the execution of a killer called Prado at the Place de la Roquette; I thought of the stern look of judgment on the priest’s face in Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1893 lithograph “Le Matin: At the Foot of the Scaffold”. I blinked slowly and thought about Tanner’s comment from Shaw’s Man and Superman about how a man about to be hanged could at least give the chaplain a black eye. In that moment, despite my stated and practiced commitment for more than a decade of non-violent resistance, I realized that I would have cheerfully kicked this hypocrite’s teeth down the back of his throat had I been given half a chance. I’m thankful now that he did not. Nobody wants to go out with hate in their heart. I wish I could say that I still don’t detest this man, that I don’t think about his smug demeanor on occasion. I wish I could say this, but I can’t. His presence was not helpful. It made the experience far worse than it had to be. If his god turns out to be the right one, I’ll spit in his eye on the Day of Judgment, and consider it a good day’s work.

The chaplain completely mistook my careful evaluation of his face as a sign of openness, the first time I’d really given him my attention. He started trying to preach to me. Swallowing my ire, I carefully informed him that I was not a co-religionist and would appreciate it if I could spend my last hour of life in silent meditation. He made a comment about how he respected all religions – an interesting assumption on his part – and then used a patently transparent pivot to return to his goal, a discourse on atonement. I understood what he wanted, and kindly asked him a second time to please leave me in peace. Another chummy attempt at obfuscating his intentions and I had a mild snap. I don’t recall exactly what I said – it wasn’t particularly sophisticated, I imagine – but I know it included me saying that I disdained his heavily marketed, doctrineless, generic, narcissistic, individualistic, and therapeutic concept of god, and that I didn’t care to hear his fucking theory on unicorns either. After that, he got the point and sulked against the wall with Tweedledum and Tweedledee.

I calmed myself, and thought of the people I loved that were somewhere inside that very building, about those that were just down the street. I thought about what they were going through on my account, about how this was like an echo of the original crime I committed in 2003, a re-metastasis of the evil I’d loosed when I was a stupid kid. I thought about how simple dying seems from a distance, about how I’d told everyone that annihilation was preferable to living in prison for life, in an attempt to give them some sort of comfort when this day came. I thought about how I’d even meant it a few times; but now, in the wild rushing torrent of the act itself, everything sure got more complicated. I thought about all of the millions upon millions of human beings that had been dragged into dark woods to be slashed with stones or metal, men and women who had been pressed against walls with blindfolds on, minds that had been led up stairs to meet a long stretch of rope. In that moment, I wondered how it was that I had ever managed to be a humanist, to think that our species had any kind of future.

I had given a lot of thought to my last statement. The things inmates say at the end never seemed all that interesting to me: clumsy, desperate words, a last attempt at throwing up some kind of bulwark against the nihil. I decided a few weeks before my date that I wasn’t going to say anything, that the time for saying words to other people was when one was alive, and I’d done that. Instead, in an attempt to keep as calm as possible, I’d memorized Wallace Stevens’ poem “Sunday Morning,” a beautiful piece that came really close to nailing how my views on mortality had changed during my time on the Row. It also felt like some sort of categorical rejection of the person I was at 23. The thing I was at 23 didn’t memorize poetry.

I closed my eyes and began repeating the lines, trying to erase the image that dominated my mind: a room bathed in spectral green light. I was out of options, out of time. Hell is having free will but no options; the only one I had left was repeating the stanzas. Although I didn’t know this for several weeks, my friend Dina had memorized the lyrics from “Blackbird” by the Beatles for this same reason. This was going to be her mantra as she watched me die. The last two lines of this song (“Blackbird fly / Into the light of the dark black night”) dovetail eerily with the ending of my own selection (“At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make / Ambiguous undulations as they sink, / Downward to darkness on extended wings”), to the point that when I read her letter describing what her intentions had been, all the hair stood up on the back of my neck. I didn’t think that was a real thing, just a sort of cheap authorial convention. As I said, I really have made some incredible friends over the years.

My recitation was interrupted by a loud banging noise. I opened my eyes, and turned to the right. Several guards passed by my cell and moved towards the door leading to the external loading area. The chaplain frowned, and looked down at his watch; I followed his gaze, and got a glimpse of the face: 5:32pm. Why was he frowning? I tried to process this, and the only thing I could come up with was: in a routine that permits no deviation, something irregular was taking place.

I looked back towards the scrum of officers gathering at the door. A captain slid to one side the tiny cap that covered the viewport. “Some people here. A whole lot of people.” I took a deep breath, and stood.

The door swung open, and a crowd of men in suits entered. A distinguished African American gentleman in a three-piece suit approached the cage. I scanned his face: nothing. I flicked my eyes from man to man: stern to flinty to severe: faces of purpose, purpose and death. And then, in the back, a man with a beard and uncharacteristically kind eyes, a man whose mouth was just starting to twitch into a grin as he registered my gaze.

And just like that, I knew.

I turned to face the black man again, who introduced himself as the warden of the Walls Unit. “Mr Whitaker, I have some news. The Governor has commuted your sentence to life.” He wasn’t smiling, exactly, but he did seem pleased. I tried to take a quick poll: Jason Clark, TDCJ’s flak, had a genuine smile. The bearded man’s joy was obvious. Most of the rest of the suits seemed ambivalent, the guards a model of indifference. Then I got to the chaplain, who was very clearly disappointed. I wasn’t getting the justice he felt I deserved, whether that was for my crime or my rejection of him I couldn’t tell. That almost made me smile. Almost.

“So what now?” I asked.

“Now we get closed down here and you take the ride to the Byrd Unit for classification.”

I nodded, about to ask what this meant, when one of the guards stepped right up to the bars. “How come you ain’t doing cartwheels?”

He wouldn’t understand my answer, so I just gave him a hard stare, the coldest arctic blast I could muster, this thug, this brute, who minutes before had been preparing to tie me down and kill me, and thought: who the fuck told you we were on talking terms now?

Instead, I turned to the warden. “So that’s it? I’m just another inmate now?” He nodded. I swallowed. “It’s been more than a decade since I was able to shake someone’s hand.” To touch anyone at all.

He smiled, extending his hand through the bars. “That’s the simplest problem I’ve solved all day.”

They used the death van to take me to the Byrd Unit, which is only a few minutes from the Walls. There I was met by the assistant warden, a captain, and about fifteen lieutenants and sergeants. I was strip-searched, given a pair of boxer shorts, and led to medical, where the entire crowd watched me answer a basic medical history battery. I guess I had retreated pretty far into myself by this point, because one of the assembled voyeurs commented to another that he thought I was in a state of shock. I looked at him for a moment before turning back to the nurse. There’s a difference between not being able to speak and knowing when not to, something every prisoner knows well.

After medical, the entire lot of us marched upstairs to classification, where all of my basic personal data was input into a computer, even though all of that information was already there. A high-definition photograph of my face was taken, my irises scanned. Somewhere along the line someone finally gave me a pair of pants, and was confronted with the riddle of how to put them on with my hands cuffed behind my back. (Answer: very slowly, very clumsily.)

I was finally led downstairs and down a long hallway. Multiple branches intersected this at perfect right angles, but I cannot recall how many now. We eventually turned right and through a crash gate into 13-hall, a two-storey cellblock comprising (I think) 44 cells. I was placed into 4-Cage. My few items of property were already stacked on the bed, save for my typewriter, which ended up going missing for three months. The door closed behind me and my cuffs were removed, and then I was alone for the first time since my shower that morning, which felt like 4,000 years ago.

The light in my cell didn’t turn off – I was under Continuous Direct Observation protocol, apparently, though thankfully this did not include the usual guard stationed right in front of my cell. I unpacked some clean clothes and settled back on the bunk, letting the noise and pulsing life of the block wash over me. My reverie was interrupted by an older male guard, tapping on the mesh screen that covered the bars that separated the cell from the hallway. He was grinning at me, but it was his nose that drew my attention, with its magnificent collection of spidery broken blood vessels. The things one remembers in moments of trauma!

“I got you some grub here, Whitaker, if’n yer hungry?”

I thought about it for a moment. I hadn’t really eaten all day, and honestly didn’t feel like I was ever going to be interested in eating anything ever again. But the man’s smile seemed truly real and he had obviously gone out of his way to stuff three brown lunch sacks with something, so I accepted.

“I could eat.”

“I got you some chicken pattie sandwiches, some fries, eggs, cheese, the whole business. Even some cake,” he added, popping my tray slot to hand the food through.

“That doesn’t sound like… you mean to tell me this is how prisoners eat at this farm?”

“Ah hell no, it’s the same trash as everywhere. I got you this from the officer’s mess.”

I was shocked. That had never happened to me before, not in all of my years in prison. “Why?” I stammered.

His smile erupted again. “Because you beat ‘em, kid. Good on you!”

I sat back, processing this. All the guards that worked the Row were volunteers. Somehow their lack of moral qualms over their work had blinded me to the possibility that not every employee of the TDCJ was a supporter of capital punishment. I began to nibble on my feast when it started to hit me: there was going to be a tomorrow. I fished my watch out of my property, and looked at the face. It was 11:34pm, and I was still alive.

I was still alive.

To be continued…

4 Comments

Deborah Allen

July 10, 2024 at 3:07 amHi Thomas, your writing is wonderful. Just wonderful. I cannot imagine the trauma you went through that day. I know trauma, only too well , what you have gone through and survived is another level.

Deborah

mark

July 5, 2024 at 12:49 amA mock execution is a form of refined cruelty.

Martina Quarati

June 19, 2024 at 12:54 pmThank you so much for this amazing work. Everyone should read it.

Alex

June 18, 2024 at 4:27 amThomas, this is a superlatively excellent work, laden with musings that transcend the solipsistic inclination of first-person narratives.The scene with the chaplain in the death house is the most poignant, with its resemblance to the epiphanous moment in Camus’s The Stranger. The banality of the horror they exert upon the condemned is nauseating, and you express that so vividly yet laconically in this essay. I’ve been reading your blog for years, and have caught many of the philosophical allusions and intertextualities in your work. Admittedly, and rather shamefully, I was also morbidly curious about the process at Hunstville that has never been described better than by you. You are an excellent writer and thinker. I’ve recently reread Discipline and Punish with your master’s thesis in mind, which has opened the text for me in places and filed in a couple of its lacunae. That was an impressive essay for your humanities degree. I hope you continue writing.